When a devastating diagnosis could have spelled an end for a long-running dance academy, it instead provided an opportunity for the founders and their studients to revive, celebrate and reconnect with themselves and their world. This is how Alzheimers gave Tarana Dance School a fresh new purpose.

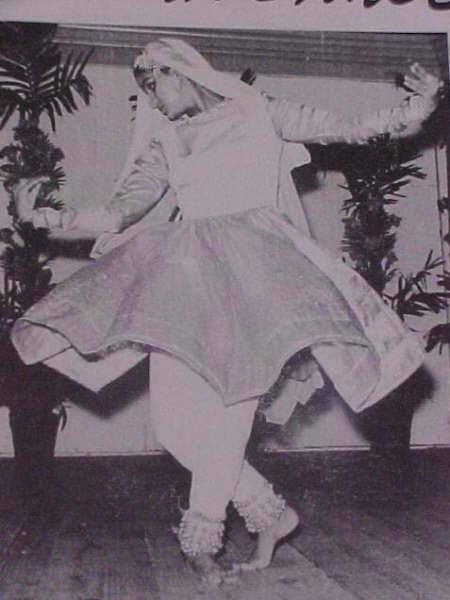

Reshmi Chetram had everything going for her — she had toured all over the world as an accomplished kathak dancer, appeared on a successful television show and ran an Indian dance fitness program.

Then in 2012, a thunderbolt struck.

“I noticed my mom’s behaviour changing,” she said. “My mom is a fun-loving, energetic business-savvy woman but she was starting to get confused.” At first, Chetram thought it might have been mood swings. But when she saw her mother’s confusion with words, numbers, losing track of things like receipts etc., she knew it was a more serious problem.

Whatever her initial suspicions might have been, nothing could have prepared her and her family for the doctor’s diagnosis. “Early-onset Alzheimer’s and a rare form of dementia that tackled the front form of her brain that takes her away her ability to speak and her motor skills,” said Chetram. “It’s a disease that’s degenerative so there’s nothing we could do.”

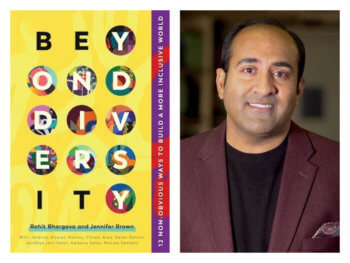

By then, the Tarana Dance School had been running for 25 years. It was her mother Deviekha Chetram’s — life’s work since immigrating to Canada. A lover of dance since she was five, Deviekha was well-known as a performer in Georgetown, Guyana but, according to Reshmi, her focus changed after moving to Canada.“After she had children, her focus shifted to educating, teaching and promoting Indian art,” said Chetram.

Chetram’s parents had moved to Canada in 1979. At that time, few were teaching Indian dance in Toronto, which made her mother’s craft all the more sought after. “A lot of families that came from Guyana, Trinidad etc. wanted somewhere to connect their kids and themselves to their culture,” said Chetram. “So a lot of people were requesting her to teach classes. And that’s how it got started.”

Deviekha taught her first class in 1989 at her home in Malvern, with five students. Immediately popular, the school grew rapidly in size as well as the avenues of dance offered. It offered recreational classes in Bollywood, Indian classical as well as Folk dance, according to Chetram. Students did not need experience to be eligible and only had to register for classes in advance in order to train. “Our youngest student is three-years-old and our oldest is 72,” said Chetram.

Deviekha would also invite instructors from around the world to teach their students at the school, including hers and her daughter’s gurus, “as an opportunity for dancers to train,” she added.

“At heart, it’s a family business,” she said. “The students who have trained with my mom, they are all like her daughters.”

Her mother’s school was where Chetram first got her feet wet with Indian classical dance, when she was merely two-years-old. Falling fast in love with the art, she decided to pursue it professionally after high school and moved to India to study at a Kathak dance institute. “I was between Toronto and India for seven years,” she said. “Through that time, I was able to perform in Canada, U.S., India and different parts of the world with their company as well as with the Toronto Dance Company.”

Her mother had intended for her to take over the school someday, said Chetram. “But I would say, ‘no mom, you do the school, I want to train and tour.’”

At the time of her mother’s diagnosis, Chetram was in the midst of setting up a dance non-profit organization and wrapping up the first season of her television show Bollyfit. Yet, no matter how busy she was, her mother’s classes had always been a part of her weekly routine. Consequently, when she was faced with the question of the school’s future, she said she “couldn’t close it down.”

“I put everything else on hold and restarted the engine around her dance school, just so the students could be around her,” she said.

Despite spending so much of her adult life on stage, Chetram said she had always been drawn towards teaching, like her mother. “My mother’s dream was my shared passion with her,” said Chetram. “It’s a desire to help the next generation of dancers who are mostly first-generation Canadians connect to their culture and heritage.”

Her love for teaching made the transition all the more easier — relatively speaking. “You know when things happen in an uncomfortable manner but once you allow it to happen, it settles and it feels right?” said Chetram. “I think it was supposed to happen.”

So much so that Chetram has added her own touches to the school. As of September, she has launched Reshmi Chetram Company, an advanced mentorship division within the dance school, “designed to advance emerging established dancers in their training and technique.”

Unlike the recreational classes previously offered, only students with a minimum of six years experience in dance are eligible for the senior program. The program includes curriculum-based weekly classes, as well as weekend dance immersives. “The weekly classes layer on top of each other for the practical at the end of the term,”she said. “The immersive is more about giving dancers an experience to get into a flow and opportunity to journal and try out their own ideas with partners — an artistic retreat for them to get an experience in creating.”

The audition brought out 25 students, out of which 15 were accepted, noted Chetram. The expertise and goals of the accepted students could range from wanting to perform on stage as an artist or opening their own dance schools. The program is meant to be more interactive, taking into account the needs of a student as an individual and accordingly streamline their training, regardless of whether they wish to train in Kathak, Bollywood etc. “Dance is simply a language through which we convey the tools they need,” said Chetram.

The company’s launch, along with her mother diagnosis and the birth of her baby, Sahil, meant she had to put offering up recreational classes on the back burner until next year. Rather than being upset, Chetram said the postponement amped up student’s anticipation for the next season. “Most people understood where we were at,” she said. “So it’s been really nice and we even have a waiting list for the next year.”

The school has gone through many phases over the years, but at its core its purpose has remained the same — a close-knit hub for immigrant families looking to connect.

With one addition — it is also a way for Deviekha Chetram to stay connected. “With the disease like Alzheimer’s the most amazing thing is that their ability to remember music is the last thing to go,” said Chetram. “So my mom can’t say hello anymore, but if you play Kathak music to her, she’ll still mouth the words.”

Devika Desai

Author

Devika (@DevikaDesai1) has a Masters in Journalism from Ryerson University. She's currently a web producer for the National Post. She has also interned at MidDay, a Mumbai-based tabloid. In her free time, she loves to read, work out once every blue moon and ask strangers if she can pet their dogs.