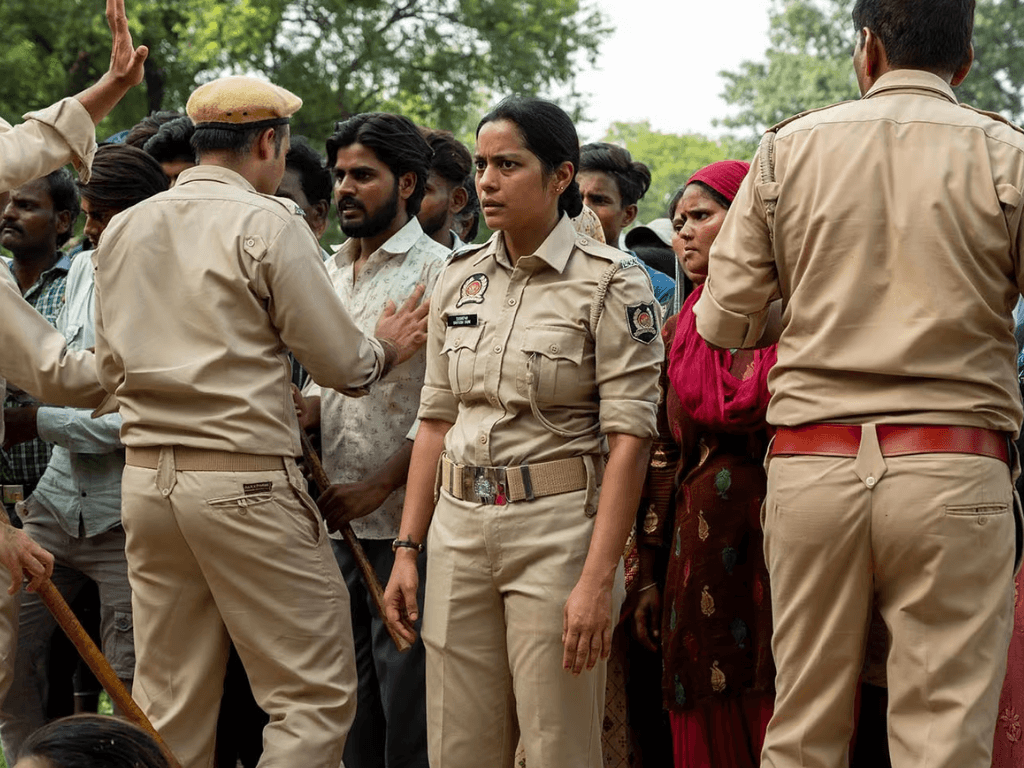

British-Indian filmmaker Sandhya Suri’s first feature film, Santosh, has been chosen to represent the United Kingdom in the Best International Feature Film category at the Oscars. Set in a fictional North Indian town, the movie features Indian actors Shahana Goswami as police constable Santosh and Sunita Rajwar as Inspector Sharma. Recently, Santosh achieved another milestone by securing a spot on the Oscar shortlist as the UK’s official submission.

The inspiration for Santosh came to Suri while directing her first feature. After returning to the UK from a research trip in India, where she examined the widespread issue of violence against women, Suri was struck by a powerful photograph. The image depicted two protesters confronting a female police officer during the protests following the 2012 rape and murder of 23-year-old Jyoti Singh in Delhi. This moment became the creative spark for her narrative.

Santosh has now been officially chosen as the UK’s contender for the Best International Feature Film category at the 97th Academy Awards. Written and directed by Sandhya Suri, the film has received significant acclaim, earning the Best International Debut award at the 2024 Jerusalem Film Festival. It premiered in the Un Certain Regard segment at Cannes and will be released in U.S. theatres on December 27, 2024.

Join me as I engage with the acclaimed filmmaker Sandhya Suri, where we discuss her journey, creative process, and critically acclaimed debut feature, Santosh.

Mehak Kapoor: I absolutely loved the film! It covered everything that needed to be seen and discussed. What does it mean to you to have Santosh, a film deeply rooted in Indian culture with an all-Indian cast, selected as the UK’s official entry and shortlisted for the Oscars?

Sandhya Suri: Thank you, Mehak. I’m so incredibly proud and happy to be on this shortlist and in such great company! It’s been overwhelming to see Santosh, a British film that was shot and is rooted so deeply in India, resonate with audiences all around the world. This is a universal story that asks questions about power, impunity and the fault lines within society and I hope making the Academy’s shortlist allows us to bring the film to even more people.

MK: Also, congratulations on winning two awards at the British Independent Film Awards (BIFAs) for Santosh! What does this recognition mean to you and your team, and how do you feel about the film’s impact thus far?

SS: Thank you so much. Yes, the recognition that the film has been getting has been marvelous. You know, we just had two wins at the Biffers. I think it’s always wonderful for the script to win because it feels like that is the essence of the film and also for my producers who just worked so hard on not an enormous budget to make this ambitious first feature look really spectacular and pretty great in scale and ambition.

So it wasn’t easy in India to shoot all summer for anybody and they made that money go to the screen. It’s also been fantastic to have it screened in many different places around the world now, and it’s helped me to understand (as the author of the piece) that it feels very grounded and real and authentic for Indians, which is a feedback I’ve been having so far from India. It also resonated on a very global and universal level.

I’ve screened in Poland, in Tokyo and everywhere, including with local audiences, not just movie buffs. It’s struck a chord with people because I think the themes we’re discussing are universal. They may be a little bit more transparent in India than they are in some other places, but they’re universal. It also speaks to Shahana’s amazing ability and the strength of writing of Santosh that it’s by her side that we stay and it’s through her eyes that we’re talking. There is a deep affection for her even though she is complicated.

MK: What inspired you to tell Santosh’s story, and how did you balance the intimate personal struggles with the broader societal themes woven into the narrative?

SS: Well, that answer can take place in two parts. The first is about the origins of the project. It began quite organically as a documentary. Like many women, especially as a British Indian who spends a lot of time in India, I have witnessed violence against women firsthand, within families, at workplaces, and in everyday life. As an artist, I wanted to explore and understand how to address this issue.

I started by working as a documentary filmmaker, collaborating with various NGOs while researching in Northern India. However, I found it incredibly challenging to film this subject matter. I felt that with my camera, I was merely observing the violence, unable to truly get inside it and understand its roots. Frustrated, I set the documentary idea aside.

Then, in 2012, following the horrific gang rape on the Delhi bus, which garnered global media attention, a photograph emerged that profoundly struck me. It depicted a female protester confronting a policewoman. The constable’s expression, enigmatic, almost unreadable, immediately captivated me. She represented an intriguing paradox: someone who holds immense power but also has none, someone who is both a victim and a potential perpetrator of violence. I realized she was the key to telling this story. At that moment, I knew this couldn’t be a documentary; it needed to be a work of fiction. Shifting to fiction marked a steep learning curve for me, especially as I ventured into the genre space for the first time.

As you rightly mentioned, the film explores personal struggles within broader societal themes. A journalist recently pointed out that this duality recurs in my work, the interplay between the small political and the big political. I aim to weave these layers so finely that the work remains emotional, never didactic. I believe a story must have a clear throughline and simplicity to function, but the foundation it rests upon can be rich, dense, and full of difficult questions. That was my intention with Santosh.

On top of that, I was working within a genre. Beyond the social and emotional layers, the plot had to function seamlessly on a mechanical level. Balancing those three aspects; the personal, the societal, and the genre mechanics, was the central challenge, from the script to the final edit.

MK: The film explores the layered complexities of gender and caste within the police force. How did you ensure these themes were portrayed with depth and authenticity?

SS: This film took 10 years to make, but it wasn’t a story of struggling to secure financing. The time was spent on extensive research, and understanding the film and its themes that’s what truly took the most time. I feel very confident about the work because of the years I dedicated to researching it, both through discussions with police anthropologists and firsthand experiences.

I’m always very careful not to create work that feels like finger-pointing or overly packed with themes I want to address. Instead, I focus on creating a tapestry, a representation of a particular place, into which I place my character. What helps the film feel natural and authentic is that it acts more like a mirror. The societal fault lines – caste, Islamophobia, misogyny, corruption, and violence, are present, but they hang casually in the air, not shouted about or forced too loudly.

There’s also a dual perspective at play. Being British-Indian, spending so much of my life in India, working there, but not living there full-time, makes me extra cautious. I want to ensure I am confident in what I’m presenting and can stand behind it fully. That’s why I feel the responses in India so far have been very positive.

Lastly, for me, it’s always about approaching everything with a light touch.

MK: Santosh and Inspector Sharma are compelling, morally complex characters. How did you develop their dynamic, and what do you think they represent in confronting patriarchal and caste-driven systems?

SS: I’m not sure about answering the last part of that. I think I’ll leave that to the audience. But what I would say is that with Santosh and Sharma, I wanted to make a complex, relationship between two women, not just one of sisterhood against a patriarchy because female relationships are complex and they can have a light side and mentorship can also have a darker, more twisted side as well. I think the thing I found interesting was the idea that Sharma can both be a mentor and guide her and stand up for women’s rights, but she can also be other things at the same time as we all can. It’s interesting for me also, because the matriarch is such an archetype, especially in Indian cinema, to work on the casting in a way which gave her a sort of vulnerability and a humanity which it could be easy not to have in the writing.

I think the casting also helped with that. They face similar situations and Santosh could be a Sharma, a young Sharma at some stage. She might see herself in a younger Santosh. I think what’s interesting in the film or the question I was looking to answer is when we talk about what are the different ways to be a woman, what Sharma represents, where is Santosh and how many different ways can we go. I think it’s about Sharma saying, look, you can either be a woman like me or you can be a sort of house flower, housewife or unwanted widow, and it’s about Santosh’s exploration of whether there’s a third way to be a woman and to confront these things.

MK: Blending procedural realism with emotional storytelling, how did you maintain the investigative tension while ensuring the characters’ emotional journeys were equally impactful?

SS: I mean, I touched upon it a little bit, but I would say that this was, again, you know, it’s all about making space in the story. You only have so many minutes. So I think the lesson that I learned through refining and refining was to make sure that the genre elements of it were satisfying, but that they also didn’t take up all the space. That left plenty of space for what my strengths are and for what I think some more interesting aspect of the film – about the relationship between Santosh and Sharma and Santosh’s own emotional story and of her management of grief as she moves through this case and her personal development. So it’s always a difficult thing.

And it was a great lesson to learn because it’s an important balancing act. But I think that I know where my interest lies in the story. And it’s about keeping the tension there, maybe in a slow burn way, but keeping that there at a certain pace. So it’s building, building, building, but giving her the space as well.

MK: By shedding light on systemic corruption and injustice in law enforcement, what conversations do you hope Santosh sparks among viewers about these pressing issues?

SS: I think that what’s been so interesting is how these themes have resonated everywhere because clearly, these are not issues only relevant to India. They may be more transparent and more frequent, but a sort of deep rot, corruption and impunity are things that happen in other places as well. I think that it’s been fascinating to see that that is also resonating with audiences, not just the story of this female’s trajectory, but also some of the other issues in the film.

In regards to India, I think it’s great what Shahana actually said about the film, which is that it doesn’t point fingers so much, because it’s more about this systemic existence of all these things, sometimes quite casually, just within the DNA of these structures.

The structures are representative of the people within it, of us, of society. It holds a mirror up to audiences to ask where they sit on these sorts of fault lines of caste corruption, violence, misogyny, and Islamophobia. For me, it’s all about a film which asks questions and creates debate. There has been lively debate after the films and even people seeing it two or three times and asking me questions later about it because there is a lot in there. And I think as a maker, I’m really happy to have made a film, which means you can go to the cinema afterwards and discuss with your friends the things within it.

I’m not so much one to dictate what conversations I had, I just really want as the maker that conversations are had. There are questions posed without any obvious answer, I don’t have answers either. But I’m just really happy that those conversations might take place as a result of the film.

MK: Shahana Goswami and Sunita Rajwar delivered deeply nuanced performances. How did your collaboration with them shaped the portrayal of these complex female characters, and were there any challenges in bringing their stories to life?

SS: Well, you know, I think I’m really happy with the casting and they were fantastic for the role. I think that keeping the complexity of the character is a constant work, of course from the script is the most important place, but then also through the casting.

I mentioned earlier that I felt Sunita’s sort of vulnerability and her physicality made Sharma already so much more human than she had felt on the page. Shahana, from the casting moment, I knew she had this right level of sort of hardness and sweetness, not just innocence that Santosh could have been, but was never meant to be. For me, she was always someone with a bit of hunger, with a bit of ambition, even if she might not have realized it till she entered the police force and someone with a bit of restraint who keeps this grief within her till at some point she can’t anymore.

So I feel that we had a very open and relaxed conversation, and they did trust me, my actors, and I. There was no diva-ness and everything was just everyone on set, my crew as well, everything was just about making the film as best it could be. It was a very tough shoot, everybody worked super hard. It was a joy working with all of them.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, I found Santosh to be an exceptionally powerful film, tackling themes like feminism, police corruption, and the complexities of caste society with great depth. The film offers a raw and uncompromising portrayal of India, one that doesn’t shy away from confronting difficult issues. The performances by the lead actresses are outstanding, with their characters taking centre stage in ways that feel authentic and unpolished. I highly recommend this film for its bold storytelling and its ability to engage with crucial societal concerns.

Wishing all my beloved Anokhi Life readers a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year!

Photo Credits: Provided by Box Office Guru

Mehak Kapoor | Features Editor - Entertainment

Author

Mehak Kapoor (@makeba_93) is an entertainment and lifestyle journalist with over a decade of experience in anchoring and content creation for TV and digital platforms. Passionate about storytelling and factual reporting, she enjoys engaging with diverse audiences. Outside of work, she finds solace i...