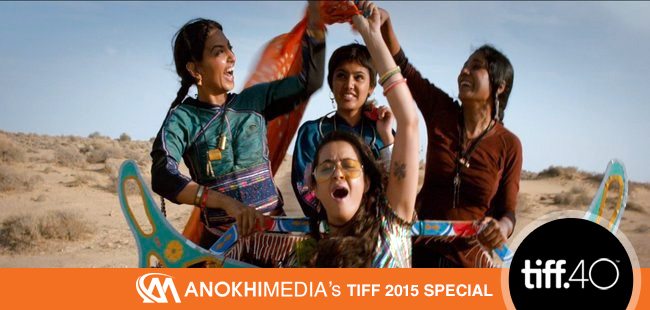

ANOKHI's TIFF coverage winds down with a lively interview featuring the cast and director of the uplifting, empowering drama Parched.

One of the more rapturously received South Asian entries at TIFF 2015 was Parched, the provocative yet joyful tale of young widow Rani (Tannishtha Chatterjee), her abused-but-resilient best friend Lajjo (Radhika Apte) and exotic dancer Bijli (Surveen Chawla), and their quiet rebellion against the archaic attitudes and oppressive patriarchal bonds of their rural Indian community. During the festival, I had the chance to sit down with the film’s stars, as well as director Leena Yadav, to dig deeper into what was a very personal, inspiring and downright run project for all involved.

Matt Currie: What kinds of things did you draw upon to connect with your characters' plight?

Radhika Apte: Even though we have not gone through the exact same story or level of oppression, I think we all go through some kind of oppression in a country which is a highly patriarchal society. You have maids who work for you, you know your neighbourhood, you know your own family, you know your family friends and you know their stories, because people talk. And this kind of oppression doesn’t just happen in a village; it happens in so many houses . . . So I think we’ve been brought up listening to such stories all our lives.

Photo Credit: TIFF

Tannishtha Chatterjee: I know someone who’s perfectly middle-class and she suffered an abusive relationship for seven years; every time we would meet her, we would say, “Why are you doing this?” Because she would have scarred eyes like Radhika’s character had in the film. After those seven years, she finally move out of the relationship, but she had lost part of the vision in her right eye by then. So the thing is, these kinds of things happen in all parts of the world . . . In certain cultures, it’s more subtle, but it still exists.

MC: Leena, what made you want to tell this story?

LY: We started with the humourous parts of the stories and said, “You know what, let’s make Sex and the Village.” Because these people talk so much more liberated, obviously, when they are alone, only with women, than we do in the cities. But when I started writing my treatment, a lot of more serious tones came in, probably because you’re reading about violence every day all over the world. Then we travelled in those villages for two to three weeks, and we met the most amazing women with the most amazing stories.

But the big thing was that it was so spirited, you know? Like, this women we met, she was bruised, and I said, “What are those bruises? Does your husband hit you?” And she said, “Oh, we’ll talk about that later; he hits me, but then, he has nothing else to do. Where else can he take out his anger? But we’re having so much fun right now.” And that’s where Lajjo’s [Radhika Apte] character came from. And that’s what life is. It’s not like a woman who is beaten is just depressed and just laying dead. I wanted the film to have that spirit — and if they are so spirited, they just need to question the norms that they have fallen into.

MC: How much changed from your initial concept of this story?

LY: Actually, it didn’t change. But it just started getting so many more layers as we researched more. And we said, “OK, we want to get this issue in, so how do we do it?” Each of those characters kind of became a carriage for, “OK, let’s address this through this character.”

Photo Credit: TIFF

Even when I went scouting for the village, I got rejected by at least 30 villages to shoot there, because they said, “More women like you are going to come here and our women will get corrupted.” And that was a younger generation, so that’s where Gulab [Riddhi Sen] got so many more layers. The younger generation is the one who are going out and seeing the cities, and they are the ones who are coming back much more orthodox. I’m finding that happening the world over. Suddenly, cultures are now trying to go 10 years back and hold onto things . . . “Oh, we were better off then; we had more system and organization. We’ve let these women out loose too much!” So I think it never ended; the script just kept getting written, and [the actors] came in with their own stories and opinions and views.

I think the process still continues because now actually, it’s not a film anymore. It’s so many things, things that we want to just say and discuss, and it’s great — that’s the only reaction that I hope for this film, that we discuss these things.

MC: So how many of the local women did you end up corrupting?

LY: [Laughs] I don’t know about the women, but the men who hung out outside our set often got into fights. They had violent fights because they could not take so much woman power.

Photo Credit: TIFF

Surveen Chawla: We all felt like this was our movie, not just [Leena’s]. We felt for every character. We would discuss each other’s characters, which was so amazing and wonderful as actors and women. I don’t think I personally have ever bonded so much with women, especially in a work environment, as much as I did here. And I think all of us would feel the same. We would exchange notes, sit down over dinners, over lunches, break times, and discuss each other’s scenes and what we would do. We would feed off each other’s energy.

MC: Leena, being a woman in a male-dominated industry, have you had trouble getting your films made?

LY: What I hate most is being called a woman director, because we don’t call the men “male directors.” I feel like I’ve been put in a box for that. In fact, when I started my career, I had decided I would never make a woman-based film, because that’s what they expect me to do. I’ve broken that [rule] now. But I want people to stop calling me a woman director. I’m just a director; I’m an individual.

Photo Credit: TIFF

MC: What was the most memorable moment in this entire process?

RA: There’s one moment for me that was the highlight of the whole thing. So, nudity is a big deal in India. We had a scene where the three of us strip and jump into the water. [Co-stars start to laugh]. We were trying to tell people don’t look, but it was a bit beyond that, and we had to have a certain amount of crew there. So we jumped into the water and then, suddenly, the [director of photography] and director improvised [and said] “Just swim from this side to the other side!” And we were like, “What?!”

TC: In the middle of the shot…

RA: I was like, “Oh my God, oh my God.” So we swam, and on the other side we were just coming out of the lake, but there was a [blockage] or something there . . . So I took the other way and went up, and they were still coming. So I’m standing there naked and the shot was over, and I’m saying, ‘Don’t go there, go here.’ And the [crew] came running with towels.

SC: The men were trying to look away.

TC: It was on the last day of our shoot. We all just took off our clothes and jumped.

LY: And that was the last step in liberation.

Main Image Photo Credit: TIFF

Matthew Currie

Author

A long-standing entertainment journalist, Currie is a graduate of the Professional Writing program at Toronto’s York University. He has spent the past number of years working as a freelancer for ANOKHI and for diverse publications such as Sharp, TV Week, CAA’s Westworld and BC Business. Currie ...