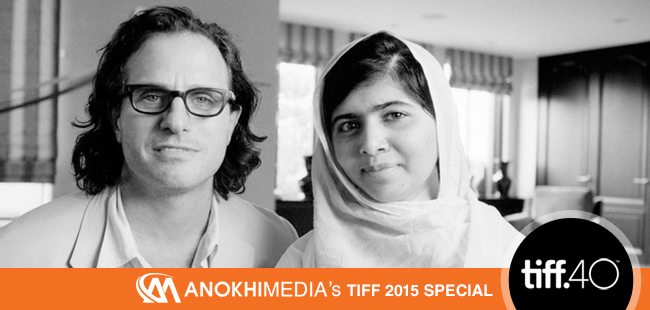

ANOKHI chats with the man behind the poignant and uplifting He Named Me Malala.

Among the most hotly anticipated debuts at this year’s festival was this intimate documentary about pint-sized Pakistani activist Malala Yousafzai. The film opened wide this past Friday to near-universal acclaim, but back at TIFF, ANOKHI got the chance to sit in for a round-table discussion with the film’s director, Davis Guggenheim (An Inconvenient Truth, Waiting for Superman), in which the acclaimed documentarian talked about getting to know the “ordinary girl” behind the global icon.

Journalist 1: Out of all the film's subjects, who was your favourite to get to know?

Davis Guggenheim: Malala and her father. I start my movies very differently; usually documentarians bring in a crew with lights and cameras and the whole thing. And suddenly things stop being real, because all this equipment comes in. I start by just walking in by myself and sit down and have a one-on-one conversation. And Malala and I sat in her office for three hours and just talked — with no agenda . . . So that’s why the movie has sort of a very personal, intimate feeling to it.

Journalist 1: What drew you to this story?

DG: Like a lot of people, I heard about this girl who was shot on her school bus — and I thought maybe that was it. But when I got to know her, I realized that that’s not why she’s interesting. Otherwise, she’d be just another victim. There are millions of people who got shot and died, but she was an ordinary girl who, when she saw something that’s not right, she spoke out and risked her life. That’s interesting. Great characters in movies are defined by the choices they make.

Journalist 2: What sort of narratives were you looking to explore throughout the film?

DG: Very early on, I was like, “This is a father-daughter story.” Clearly, I could’ve told a geopolitical story about the rise of the Taliban, the rise of fundamentalism, the West vs. East. And I felt like that in itself is interesting, and it’s pretty well-told in the book [I Am Malala], but I wanted to tell something very intimate. I felt like, as a father, I want to know how to be good father, and if I met [Malala and her family] and asked them questions, I can glean something from them. For me, if I want to know those answers, then that will come through in my movies.

Journalist 2: What was your most difficult challenge in making this film?

DG: The story structure is very complex. It’s the hardest movie I’ve ever had to make. We had many screenings of cuts that just didn’t work . . . because we intercut between the past and the present. And then the animation was a big challenge; we didn’t know if that would work or not. It was sort of a creatively different choice, you know? Would these romantic, hand-drawn images work in a verité documentary?

ANOKHI: Following up on that, how did that decision come about — to use these animated segments?

DG: For two reasons. [Malala] would tell these stories about Malalai — about this girl a hundred years ago who rallied the Afghan people to fight against the British and this girl who spoke out and was killed for speaking out. Malala spoke out and was almost killed for speaking out — to me, it was like “You can’t write a story like that.” The story of [Malala’s] father naming her and putting her name on the family tree, writing the first woman’s name on the family tree — these were amazing storytelling moments, but how do you put that in a documentary? The animation became the way to do that.

Also, I was frustrated with the imagery that comes out of that region to the West. We get news reports of scary men killing people, over and over again. It feels scary and it feels intractable, it feels unsolvable. And that’s a problem, because the global South is a very rich part of the world, misunderstood by the West. The Muslim world is a very peaceful world mostly; only a small fraction did these terrible things. So if I use those same images, it’s almost as if I would be repeating that. I would have to find another kind of imagery to tell that story. And it came from [Malala and her father]; their imagery was very romantic, very lyrical. So instead of telling the battle of Maiwand from a 51-year-old male’s point-of-view, the imagery was like how a young girl from Pakistan would imagine it.

ANOKHI: We’ve all seen Malala up at the podium, delivering these fiery speeches; we’ve seen Malala the icon. But when you actually started having conversations with her, was there something that surprised you, one quality that stood out once you got to know Malala the girl?

DG: I think the thing that I have to keep reminding myself is that she’s an ordinary girl, and that it’s dangerous for us to make these people superhumans. Now, you think she’s this icon who’s done this extraordinary thing; but when she was in Swat, she was a normal girl. The girl sitting next to her at the desk could’ve done the same thing, but she didn’t. [Malala] chose to risk her life, her father chose to risk her life, and that’s what made them extraordinary. They weren’t born extraordinary; their decision to do what they did made them extraordinary. And that’s an important lesson. [If] I feel like I could never do that, only extraordinary people can do that . . . that’s a dangerous thing, because then you’re basically leaving the tough choices for other people.

Journalist 4: There’s a scene in the film where you’re talking to Malala about how she has a difficult time talking about her suffering. Was there anything else that you found about her personality that just didn’t come through in the film?

DG: Of any person I’ve ever made a film about, she’s the most open person I’ve ever met. The suffering question was really the one question she had a hard time answering. And I think she honestly couldn’t access it as a person. Part of it I think may be — and this is only speculation — part of it could be from her trauma, but also generally part of it is that she feels like, right now, there are many, many girls suffering; part of her feels like “Why would I complain if there are other people who are still suffering more than I am right now?”

Journalist 5: Where do you think the line should be drawn for parental responsibility and social responsibility — protecting your family, but also protecting your civilization?

DG: Would you risk your daughter’s life if you knew that she would be a target?

Journalist 5: Probably not.

DG: The thing [Malala and her father] would say, because I’ve heard them answer this, is that . . . they believed to their core that speaking out is your duty, it’s part of your responsibility as a citizen, and risking your life is just one thing you do to do that. That’s pretty amazing; that’s living with true principles.

Journalist 5: Why do you feel that the Taliban wants to eliminate the education of women?

DG: It’s very interesting, because at first they didn’t; they were just after power. It’s a patriarchal society, it’s a society where if a woman goes to a doctor’s office, they don’t write down their name, they say “wife of Davis” or “daughter of Davis”; so women don’t even have names in so many parts of society. It’s a power structure that was in place for a very long time, and when those things shift, it’s a threat and any power that feels like their power is being taken away from them wants to fight back. These girls suddenly want to become doctors, they want to become lawyers, they ask tough questions.

Main Image Photo Credit: TIFF

Matthew Currie

Author

A long-standing entertainment journalist, Currie is a graduate of the Professional Writing program at Toronto’s York University. He has spent the past number of years working as a freelancer for ANOKHI and for diverse publications such as Sharp, TV Week, CAA’s Westworld and BC Business. Currie ...