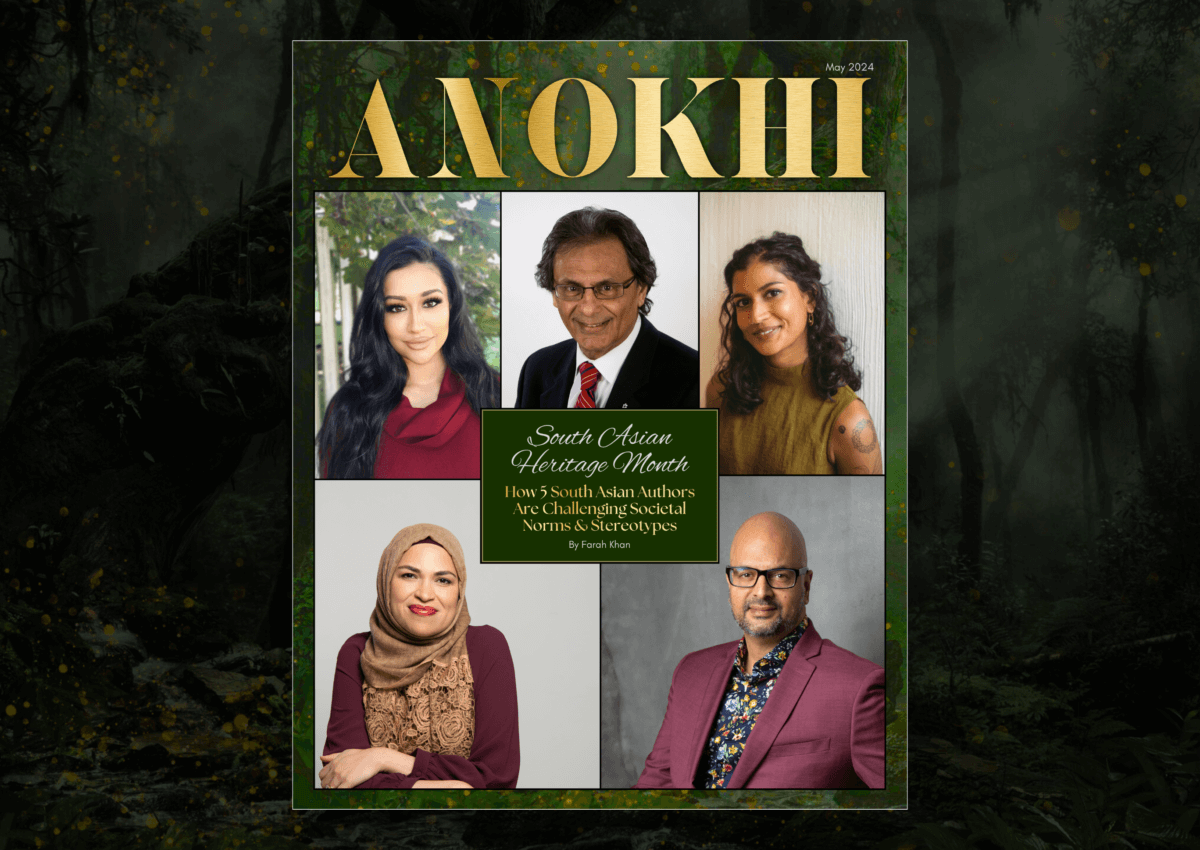

South Asian Heritage Month: How 5 South Asian Authors Are Challenging Societal Norms & Stereotypes

Cover Stories May 08, 2024

Celebrated yearly in May, South Asian Heritage Month in Canada is a period dedicated to celebrating and acknowledging the rich cultural heritage, history, contributions, and diversity of South Asian communities across the world. The goal is to nurture inclusivity and encourage understanding and appreciation for the diverse traditions, art, language, customs and cuisine of the many South Asian cultures.

In addition to fostering a sense of community pride within the South Asian diaspora, the education and awareness not only helps battle negative stereotypes, it also promotes solidarity between different cultures in a heavily multicultural society, offering a deeper perspective on the complexities of South Asian cultures.

South Asian Heritage Month is celebrated in Canada as part of the Asian Heritage Month, officially declared as such in May 2002 by the Government of Canada. In United States, South Asian heritage is celebrated throughout the year with varying months and dates depending on geographical location. In the United Kingdom, the month-long celebration takes place mid-July to mid-August, coinciding with the independence days of multiple South Asian countries such as India, Pakistan, Bhutan, Maldives et cetera.

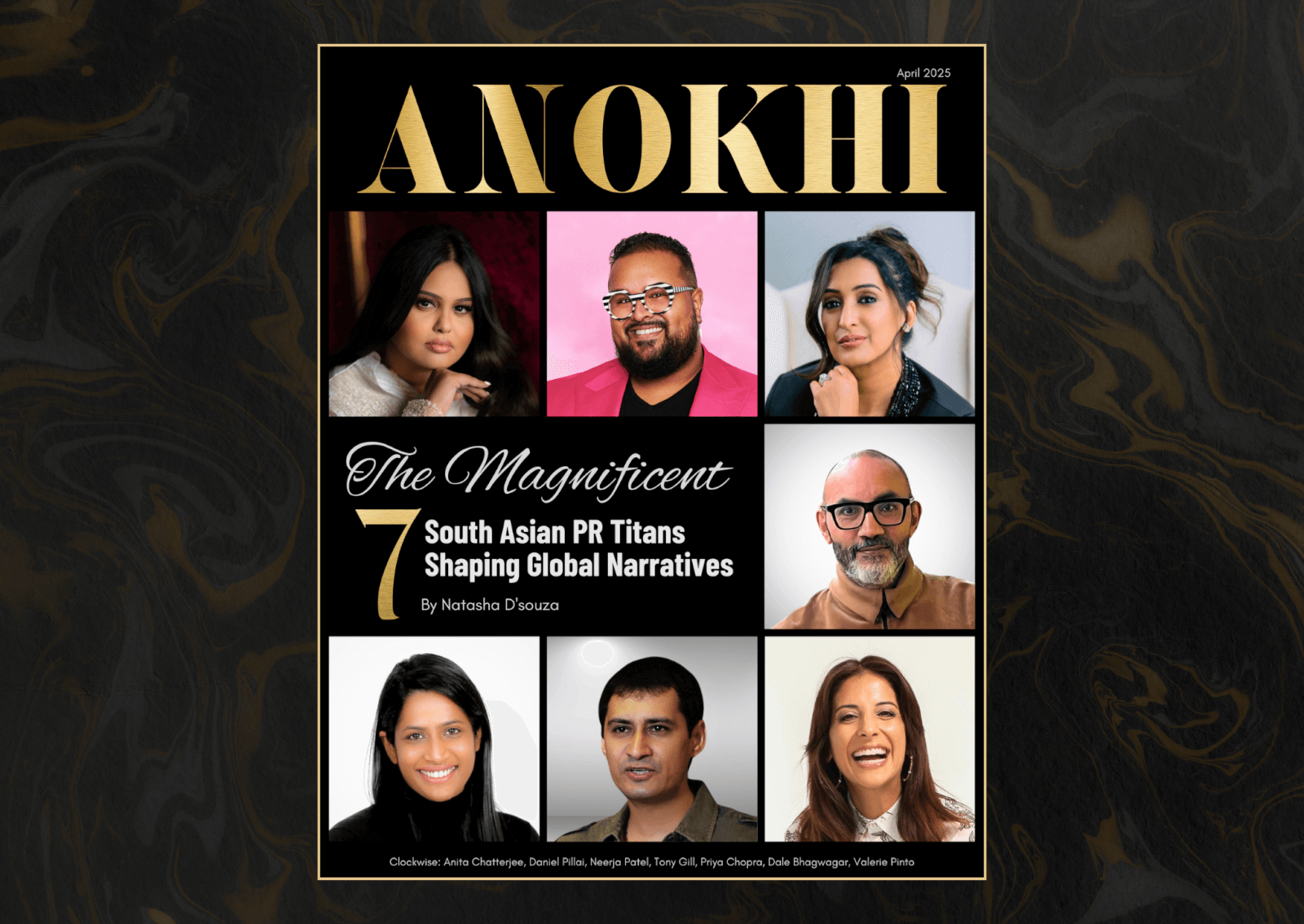

This year, ANOKHI is proud to add to its celebration of everything South Asian by shining the spotlight on 7 South Asian authors in Canada who have not only made their indelible mark in the literary world, but are also using their creative juices to help raise funds for a worthy cause in Toronto.

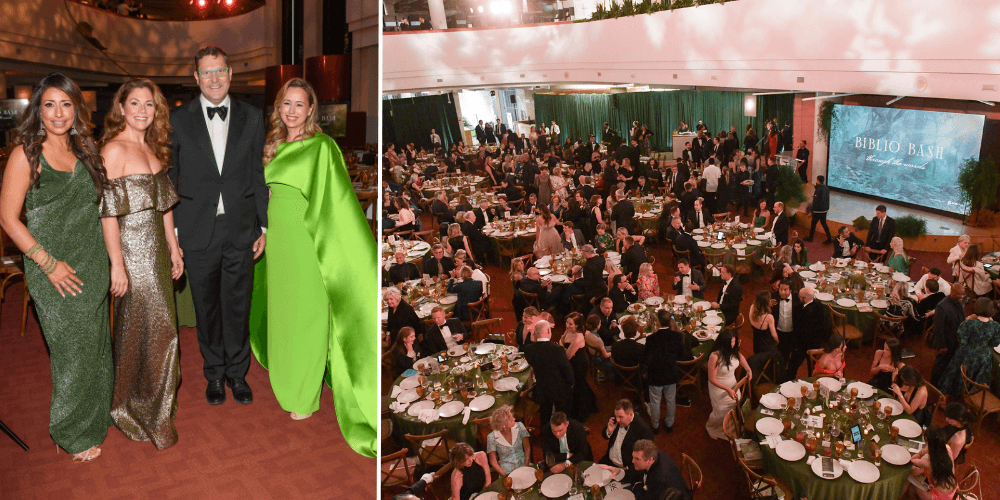

ABOUT BIBLIO BASH

Biblio Bash is one of Toronto’s premium annual black-tie fundraising events, raising funds for the Toronto Public Library and its various public programs since its inception in 2017. Over the past 8 years, the event has “raised over $5.3 million dollars to help over support Toronto Public Library’s highest priority needs and assist some of our city’s most vulnerable residents.”

- In 2023, $1025,400 were raised in support of ‘Leading to Reading’

- In 2022, $835,307 were raised in support of ‘Internet Connectivity Kits’

- In 2019, $756,838 were raised in support of ‘After School Clubs and the Bookmobile’

- In 2018, $704,379 were raised in support of ‘Youth Services’

- And in 2017, $604,475 were raised in support of ‘Digital Innovation’.

Biblio Bash 2024 (presented by Fitzrovia) took place on Thursday April 25th, where the Toronto Public Library Foundation (TPLF) surpassed its fundraising targets by reaching a record-breaking $1,071,550. Over 450 guests attended the charity event, including library lovers, business leaders and philanthropists, among them 38 notable authors

This year’s gala was dedicated to TPLF’s Newcomer Community Initiative, which aims at helping newcomers in Canada by providing crucial settlement services such as:

- Having welcome resources in over 40 languages

- Expanding critical outreach for newcomer programs and services

- Financial literacy programs and business entrepreneurial support

- Continue and expand it’s programs assisting newcomers in securing employment, learning English, enrolling children in school, finding residence and more.

The South Asian diaspora understands all too well, the struggle of being newcomers in Canada, the challenges that come with settling in a new land, and the tremendous amount of resilience, hard work and perseverance required to, in simpler words, ‘make it’. Public library services are crucial in easing the process, and work as a bridge connecting those in need with the necessary resources.

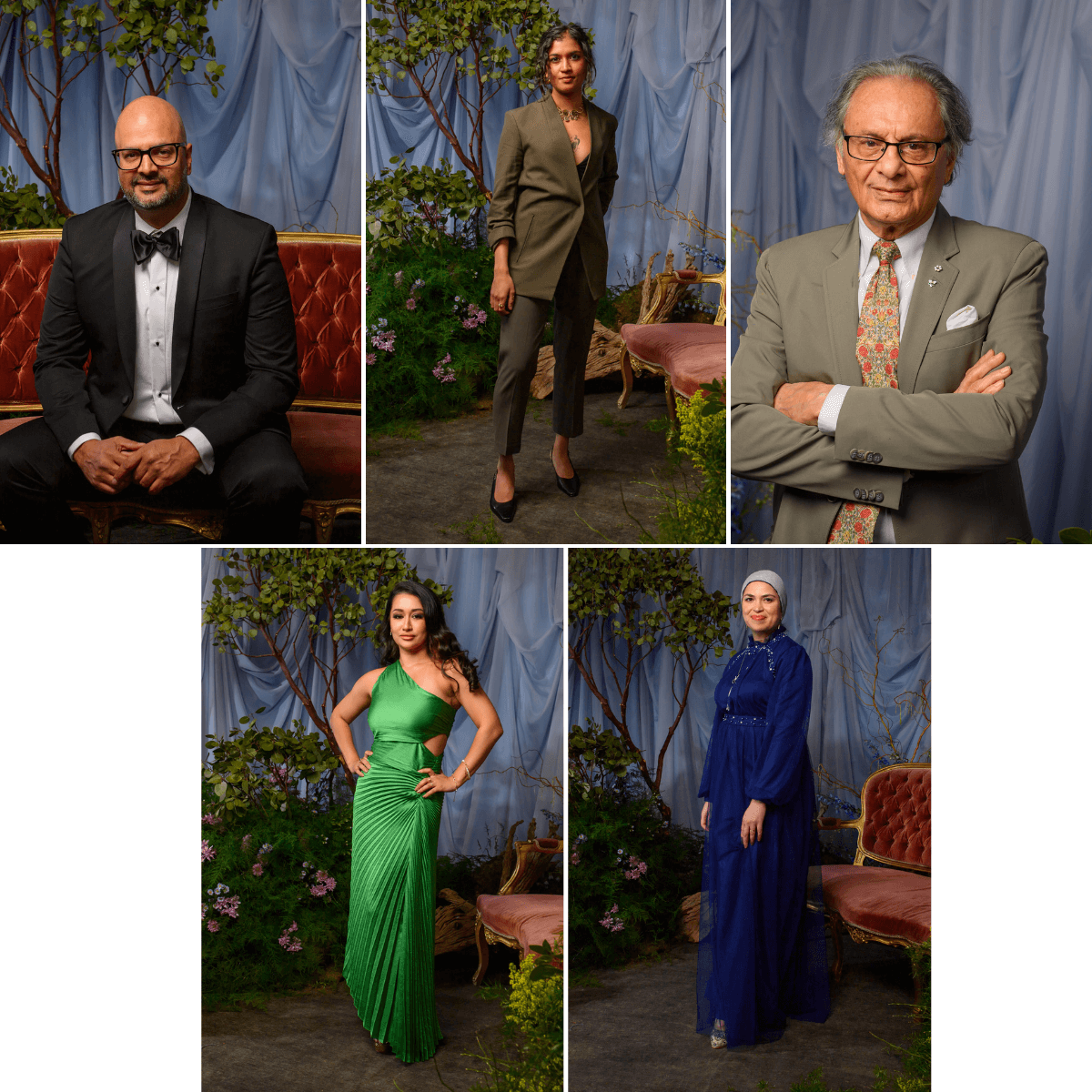

38 notable Canadian authors were present at Biblio Bash 2024 (with their newest books) and lent their support towards this worthy cause. Among them were a few South Asian authors, and we had the opportunity to speak to five of them to gain their insights.

SOUTH ASIAN AUTHORS WE ARE FEATURING:

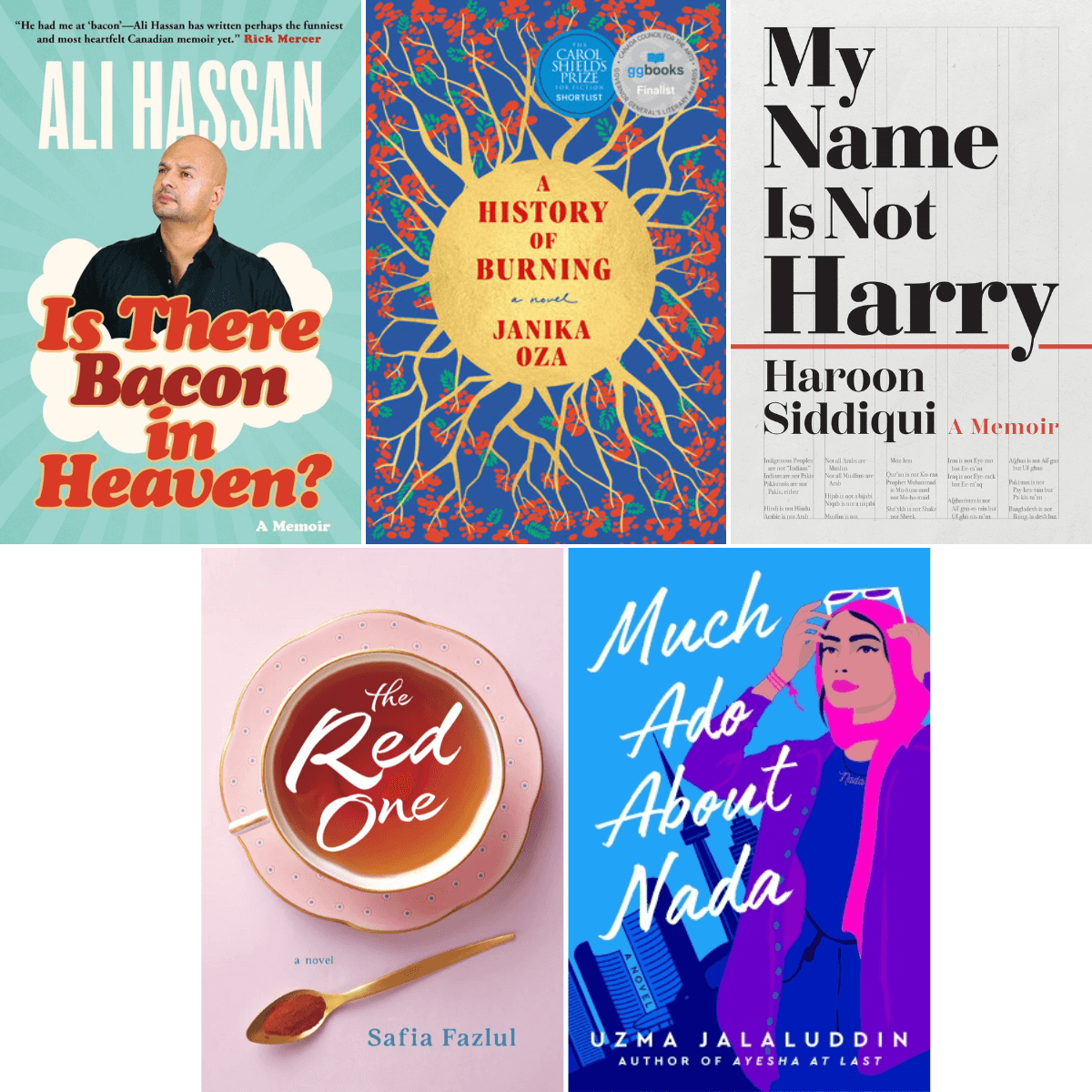

Ali Hassan is an award-winning Canadian stand-up comedian, actor, and radio and television personality. He is also known for CBC Radio’s “Laugh Out Loud” and “The Debaters.” Book: Is There Bacon In Heaven?

Haroon Siddiqui is a Canadian newspaper journalist, columnist and editorial page editor emeritus of the Toronto Star. He is also a Member of the Order of Canada. Book: My Name Is Not Harry

Janika Oza is a Toronto-based writer, who has won multiple awards for her short fiction work, and has received support from the Toronto Arts Council, the Ontario Arts Council, and the Canada Council for the Arts among others. Book: A History of Burning.

Safia Fazlul is a Bangladeshi-Canadian Author. Book: The Red One.

Uzma Jalaluddin is a Toronto-based bestselling author and a former contributor of The Toronto Star and The Atlantic. Her bestseller Hana Khan Carries On (2021) is currently in development for film by Amazon Studios and Mindy Kaling. Book: Much Ado About Nada

ANOKHI LIFE: How does your South Asian heritage influence your writing, both in terms of themes and storytelling techniques?

Ali Hassan: The weekends of my youth were spent, almost exclusively, with South Asian family friends of all backgrounds. If my parents weren’t socializing in friends’ homes, they were attending musical evenings, poetry recitals (mushairas), and various South Asian concerts, which they would often take (read: drag) us to. My upbringing was deeply South Asian, rooted significantly in culture over religion, and so it stands to reason that my writing – given how personal it is – would be heavily influenced by that.

Haroon Siddiqui: You know the old saying – once an Indian, always an Indian. Or, Pakistani. Or Bangladeshi. Or Sri Lankan. And not just because of the food, I still eat daily what I grew up eating. But beyond that I have seen things from my Indian eyes, from my South Asian eyes, my Third World eyes, f my Southern eyes, and my Muslim eyes and my minority eyes, which have now been my Canadian eyes for a long time. So, I see things slightly differently than the majoritarian point of view. But for many critics in Canada those have been deemed illegitimate lenses. But my viewpoint, that has been that’s their problem, not mine. I just do what I need to do.

Safia Fazlul: Admittedly, having spent all but the first year of my life outside of South Asia, my writing style and storytelling techniques are more aligned with Westernized contemporary literature. However, my themes are directly inspired by my South Asian background, particularly as a first-generation immigrant from Bangladesh. My characters wrestle with cultural identity, the contrast of Canadian and South Asian gender expectations, and, of course, family relationships within highly patriarchal South Asian communities. Parental pressure and control is something I always explore, even if I consciously try not to, because its significance is just so unavoidable as a South Asian.

Uzma Jalaluddin: All of my books feature characters who are first or second generation desi, and in fact also have Hyderabadi roots, just like me! In addition, the personality and background of my characters is heavily influenced by my own South Asian identity. They live in extended families with grandparents, they eat culturally specific food like biryani, dosa and idli or bhagara bhaigan, and they wear desi clothing to weddings or to attend events in the mosque. It is important to me as a South Asian, Muslim writer, to showcase the details that would have made me smile in recognition, as a reader!

AL: How do you see the role of literature in addressing and challenging societal norms and stereotypes, particularly those related to the South Asian diaspora?

Ali Hassan: Literature offers us insight into culture, marginalization, colonization, historical perspectives, lived experiences and so much more. In a time of heightened fear and discrimination towards so many, especially people of colour, I think that literature has never been more important.

Haroon Siddiqui: The role of literature is the same as that of the media or, more specifically, mainstream media, which is to challenge cliches and stereotypes, challenge majoritarian cliches and stereotypes about minorities, especially those from BIPOC communities. Most of the public discourse in North America, including Canada, has been colonial. A colonial view of the Indian who is uncivilized, the Indian who is a ‘fakir’, as Churchill called Gandhi. I remember the time when even the Indians from India did not want to be identified as Indian, given the overwhelming negative coverage and negative view of Indians. And ironically, now they have become more Indian than Indians, given now that India is fashionable and is in the news. Similarly, there was the constant whining about the so-called ‘Islamic bomb’ in Pakistan but never about a ‘Christian bomb,’ or ‘Buddist bomb’ or ‘Jewish bomb.’

Such cliched portayals had to be fought. Fought every inch of the way through the 1970s and 1980s. People like Professor Harish Jain at McMaster University, myself, and many Indians and other South Asians who formed various committees, and took on the Canadian newspaper, television and advertising industries. Things have improved since but problems remain.

People from minorities still feel the need to mould themselves to majoritarian expectations, to majoritarian prejudices. The views that Indians are bad, Muslims are very bad, and Indians and Muslims and others are catering to those prejudices to sell themselves or sell their books. Our job is to constantly challenge them to hopefully eradicate those cliches and stereotypes.

Without being arrogant – we South Asians are a people of thousands of years old, multicultural civilizations. I come from that civilization. I come from a great faith, great religion. I’m confident in my identity. So that’s why the name of my book is ‘My name is not Harry’. I’m not Harry, and you need to stretch your muscles and learn how to say my name.

Safia Fazlul: I believe literature may be the artform that is most capable of confronting the general stereotyping and pigeonholing of South Asians in the diaspora. A novel keeps its audience actively engaged with the thoughts, history, and actions of its characters and this intimacy encourages a deeper understanding of the “other”. The more people read books with a variety of South Asian characters, the quicker they will conclude that we aren’t all the same. Even if many of us may gravitate to a certain career field or come from families with similar power dynamics, we are far from a monolithic people. Reading South Asian characters and writers is the first step to understanding our rich and diverse backgrounds and the unique struggles of first and second-generation immigrants. This is, of course, true for all people of all ethnicities – the more we read about each other, the more we humanize each other.

Uzma Jalaluddin: Books are always a source of disruption and resistance, simply through their existence. Some books are considered so dangerous, we still have book bans around the world, even in Canada and the United States! As a South Asian, visibly Muslim woman who is also the daughter of immigrants, I know first hand that writing my stories into existence, with all their complicated characters living joyful and nuanced lives, is it’s own act of rebellion. I wish it weren’t the case, and yet I write on.

AL: Can you share any personal experiences or anecdotes that have shaped your writing journey and perspective as a South Asian author?

Ali Hassan: My father was an English teacher, which meant a few things. 1. We would never want for a staple, envelope, or stationery of any kind. 2. Any grammatical errors – written or spoken – were subject to critique and review. 3. My father taught an English class called ‘Third World Fiction’ for nearly 30 years. His 10000-book library was stacked with numerous South Asian authors, including VS Naipaul, Salman Rushdie, Rohinton Mistry and so many more. Curling up in the basement and savouring these books was like a journey into the lives of so many diasporic Indian characters, and subconsciously

shaped my own aims to write.

Haroon Siddiqui: I have not personally faced any racism in this country, which may be a function of the fact that I worked in a powerful industry, newspapers. This is not to say that there is no racism, as the Indigenous people will readily testify, and minorities will testify. The point of view used to be ‘when in Rome as Romans do’. And my point? No, you don’t. I follow the law, and I’m not going to cater to your prejudices and change myself and distort my identity and contort myself to appeal to you. So, my name is not Harry.

I used to be in Manitoba and the Premier of Manitoba at one time was a Conservative, Sterling Lyon, who used to call me Harry, and I said to him, “Premier, I’ve told you before. My name is not Harry. I don’t look like Harry. I don’t want to be Harry. My name is Haroon.” So that’s the anecdote that then shaped the narrative of this book, which is an assertion of one’s identity. Respect your heritage. Respect who you are, your culture and your identity. And your name is as valid as anybody else’s.

Janika Oza: The genesis of my novel, A History of Burning, was actually in my own family history, inspired by the experiences of my community. Briefly—my great-grandfather migrated from India to East Africa under the British to work at a railway station, and three generations of my family were settled in Uganda until they were expelled in 1972 by the dictator Idi Amin. But growing up, I knew so little about that past, because there is so much silence in my family and community when it comes to talking about these heavy and sometimes very traumatic memories. I think this is quite common across many cultures, but particularly among South Asians, there’s often a reticence to talk about painful memories or to address past hardship—the idea is that we should just move forward, that there’s no sense in digging anything up. And at the same time, many people and especially those of my generation are starting to recognize how nothing can really stay buried, and also how much healing and connection can come from beginning to share and speak about those difficult memories. I came to writing this novel out of a deep curiosity to know more. There was an urgency to that feeling that I followed, and also a lot of love and care, because it’s personal: it’s my parents and grandparents and aunties, a history I’m descended from.

Safia Fazlul: I spent my childhood in Norway, where I was the only brown-skinned kid in a school full of blondes. Desperate to fit in, like most immature children are, I downplayed my South Asian roots and actively tried to be more European. This changed when I moved to Toronto, which is a much more diverse city than Oslo in the late 1990s. Being a South Asian in Toronto did not feel weird – yes, you could be laughed at if you ate curry for lunch at school, but at least countless restaurants in the city served it. I began to feel more comfortable in my South Asian skin and finally started seeing the beauty of our culture. Because of this contrast I experienced early in my life, I am hyper aware that in the process of writing about South Asian communities, I must be careful not to criticize our culture to the point where it’s judged as inferior. I battle this by creating realistic characters that are not only products of their cultural upbringing, but also their own personal choices and unique histories.

Uzma Jalaluddin: During the years I spent drafting my first novel, AYESHA AT LAST, I was scared that no one would find my very Brown, very Muslim characters relatable or interesting. I enrolled in a summer writing workshop at the University of Toronto (my former alma mater) with the intention to find out if readers outside of my community would be able to relate to my characters, or find my story, which focused on South Asian characters finding love in Toronto, interesting. I remember the first time I read a passage, which featured main character Ayesha chatting with her grandfather, and the class – who were not desi – laughed at my jokes and enjoyed the narrative. I was so relieved!

AL: Could you provide us with some insights into your newest book (that we are spotlighting during Biblio Bash 2024)? What is the overarching purpose of your work and the core message you aim to convey to your readers?

Ali Hassan: My book and a lot of my comedic work is about the quest to belong, the search for one’s identity, and the meaning within that identity. My book was also a love letter to my children, and to my parents, particularly my late father. And finally, the book also explores the idea that maybe the occasion strip of bacon isn’t so bad??

Haroon Siddiqui: Canada is a multicultural nation constitutionally, which means that there is no official culture. All cultures are equally valid. So long as everyone stays within the law, the rest of the demands put on minorities are humbug, an assertion of majoritarian views, majoritarian pressures to behave like “me”. No, I’ll not behave like you, I’ll retain my identity. I’ll retain my name, I’ll retain my faith, I’ll retain my culture. I’ll retain my food. And I’m proud of who I am. That is a real message. This book is especially for the younger generation – you don’t have to change your name. You don’t have to go bar-hopping, you don’t have to go golfing to succeed. You succeed because you’re good at what you do.

Janika Oza: My debut novel, A History of Burning, follows four generations of one Indo-Ugandan family across about a hundred years and multiple forced migrations and lands. It begins with a teenage boy who is tricked into leaving India for East Africa to labour on a railroad for the British, and follows his family as they grow and migrate and resettle. It’s a story about complicity and resistance, about the lengths this family will go to to secure their own place in a shifting world, and about the stories and memories we do and don’t pass on. At the heart of my novel is the idea of community and collectivism, what it means to belong to a whole—whether a family, a land, a movement—and all the chaos and beauty of navigating that space. And crucial to the idea of community is a consideration of who is included and who is excluded, who is made central and peripheral. I hope readers will reflect on that notion, in the novel and in their own spheres, and the possibilities of solidarity—because our fates are intertwined, because we need each other.

Safia Fazlul: The Red One is my second novel and its core purpose is to shed light on a variety of problems women in the South Asian diaspora face today. The story revolves around Nisha, a seemingly perfect and happy Indian housewife living comfortably in the suburbs. Beneath the façade of married bliss, she is struggling with a drug addiction and the psychological fallout of childhood sexual abuse that was covered up by her family to “save” her reputation. She endures a phony existence that pleases her parents until she meets a man she calls The Red One, commits adultery, and her deceptively perfect life falls apart.

I hope readers of the novel, especially readers who consider themselves a part of the South Asian community, walk away with a desire to discuss the importance of not shaming and blaming our girls and women for being abused. I also hope the novel inspires discussions about recognizing and prioritizing mental health more in our community.

Uzma Jalaluddin: My third novel is MUCH ADO ABOUT NADA, and it is my most romantic and angsty book to date – my husband says it’s his favourite! The novel is loosely inspired by Jane Austen’s PERSUASION, and it is a second-chance romance that partly takes place in a massive Muslim conference in Toronto. I wanted to explore regret, it’s role in the lives of younger people, and the difficulties in transforming or course correcting your life after a significant failure. I also wanted to dive into a topic I find fascinating – what does female ambition look like in the South Asian, immigrant community, and what unique challenges do we face in our journey towards success?

AL: What advice would you give to aspiring South Asian writers who are seeking to tell their own stories?

Ali Hassan: Take a look at @BrownHistory on Instagram. It’s such a great reminder about how many compelling, beautiful, and often heart-wrenching stories our people and the diaspora have to tell. Even if you don’t have a destination for your writing, write for writing’s sake. Your work will never be a waste.

Haroon Siddiqui: There is no money in writing, that advice I can give you [laughs]. Write on the side, but get a day job, that’s my simple advice. Writing is a portable skill. What people don’t realize is whether you’re an engineer, or a doctor, a banker or an architect, you need to be able to speak clearly. You need to be articulate, you need to write well and speak well. So, even if you don’t earn a living as a writer, you need to learn to write well, you need to learn to speak properly. and that’s a very valuable asset to have, but writing will not give you a living. The media are in decline, there are few or no jobs.

Safia Fazlul: I would say, most importantly, be your own loudest and peppiest cheerleader – you will not complete your book until you wholeheartedly believe you can. Expect and accept rejection, but don’t allow it to shatter your confidence in your story. Respect and learn from editors and other writers because there’s no correlation between the size of one’s ego and the extent of their talent. To South Asian woman writers, specifically, I would say to unashamedly pursue your aspiration. It is commendable to strive to be a super wife, mother, daughter, sister, or grandmother, but there is no road faster to misery and resentment than giving up on your own dreams. Set time aside for yourself and your writing, even if you can only spare a few hours per week. Fulfilling a dream is not selfish. Your ambitions are as important as anybody else’s. Your voice is valuable.

Uzma Jalaluddin: My advice is to keep reading books in your genre, and across all genres, to read other South Asian and diverse authors, and to try to find your community. Being a writer is a lonely business, and it helps to have friends, cheerleaders, and allies – they’re not always the same people!

AL: Biblio Bash 2024 will be raising funds to provide opportunities for newcomers to Canada. Please tell us about your support for this initiative. What is the importance of public Library services when it comes to South Asian newcomers (individuals as well as families) settling in Toronto. How do you recommend they benefit from these services to ease into their settlement process?

Ali Hassan: When I think about the South Asian immigrants who came to Canada from the 60’s through to the 90’s, I think of people who had an interest in education first and foremost. For themselves and for their offspring. Now, many of the immigrants who come here are so squeezed financially that many can’t think of education; they are just working to survive. I am a firm believer that the library can provide people with the smallest of gifts – like a respite from the heat or cold, some time alone, an opportunity to escape into reading – or the largest gifts, like educational programs, learning tools, and consultations with settlement workers. The key is to know about these programs, and to get involved with them.

Haroon Siddiqui: The library systems in Canada, particularly in Toronto have always been very welcoming places, and a lot of immigrants have always gone there. They’ve gone there to read books in their own language. Mayor Olivia Chow, for example, speaks about her mother used to go to the library to read Chinese books. I remember from my time in the 1970s, libraries — including the John Robarts Library at the University of Toronto, always had books in Urdu and Hindi and Telugu, and so on. So those have been welcoming places, places of equity, welcoming of everyone.

Secondly, libraries surround people with the printed word — books, newspapers, manuscripts, treasures that predate the Iphone. For the hyounger people, esprcially, libraries cultivate a love for the printed word, the joy of turning a page and discovering things and being lost.

So libraries perform a great service, not only in terms of equity and inclusion, but also for expanding our literary horizons and our love of the printed word, books and newspapers.

Janika Oza: This cause feels particularly resonant to me, not only because of my family’s migration story but also because I worked in the settlement sector in Toronto for some time, first as a refugee settlement counsellor and then as a school settlement worker in the TDSB. Trying to navigate all the unfamiliar systems when you’ve just moved to a new country can feel completely unintelligible, honestly—and settlement services like those available in the library do so much to just improve access to those supports, whether it’s around housing or employment or language classes. And so many settlement workers are immigrants themselves, so there’s a real sense of care and understanding in the work. Migrating can be so isolating, and this is one way of tapping into the community that already exists to offer support through it.

Safia Fazlul: I am thrilled at the very existence of the Biblio Bash; what a brilliant idea it is to have a glitzy annual gala where generous donors, passionate volunteers, and authors from all walks of life come together to help our public libraries. Public library services are, without any doubt or hyperbole, vital to the successful settlement of South Asian newcomers. Many South Asian immigrants, like my family and I did back in 1998, come to Toronto with little but a strong drive to be a part of Canadian society. Of course, willpower alone is not enough to find a job or improve English language skills; newcomers need practical solutions like access to the Internet, a printer, ESL materials, and so on – all of which are available at the library for free.

I have recently learned that newcomers can also contact settlement workers through the library. These workers can help them find a job, get their driver’s licence, and enrol into free ESL classes. For South Asians coming to Toronto without any family members, just having a person available to help them integrate into Canadian society can ease the loneliness of being in a new country. There are also English conversation circles that gives newcomers a chance to practice their new language in a friendly environment.

Uzma Jalaluddin: The Toronto Public Library system played an incredibly important role in my own writing and reading journey. I grew up using the Scarborough locations of the TPL, to take out books, watch movies, listen to music. I visited the library with my family on a weekly basis, and sometimes several times a week. As a book-nerd, I had the world at my fingertips. I still think of libraries as magical places, safe spaces, and a cultural jewel in any functional city. Many of my family members, as newcomers to Canada, made use of the multilingual services by borrowing newspapers, magazines and books in Urdu – it was a little taste of home. I tell everyone to get a library card, and to make use of the wonders of the Libby app, which is my most favourite, and most used app on my phone!

Here at ANOKHI, we encourage everyone to share this article with your networks to support South Asian authors, so that we can continue highlighting our stories worldwide.

Farah Khan

Author

Farah joined ANOKHI LIFE while finishing up her degree in English Literature and Writing at the University of Toronto. Her position since then has expanded across all departments, everything from office administration and corporate affairs, to ANOKHI's online presence and events. . .