The #MeToo movement grabbed headlines in North America and the world. However when it came to Bollywood and the Indian film industry, the initial spark quickly seemed to have flickered out and left us wondering, why couldn’t the #MeToo movement gain traction there? We take another look.

The #MeToo movement began in 2006 after activist Tarana Burke, a social activist began using the phrase in her social media network as a movement that addressed sexual harassment and sexual assault. Then, in 2017, the hashtag gained national and worldwide attention and was popularized by celebrity actress Alyssa Milano as she began the movement with her famous tweet: “If you’ve been sexually harassed or assaulted write ‘#MeToo’ as a reply to this tweet.” The ground shifted. Fast forward to February 25th, when the now infamous media mogul, Harvey Weinstein, was convicted of criminal sexual act, rape, and predatory sexual assault. This momentous court judgement is demonstrative of the progress that has been made towards the #MeToo movement, but there is still that needs to be done both in North America but also worldwide. In an interview with New York Times, Burke noted, “The outcome of the Weinstein case should be seen as fuel to keep survivors and our allies motivated for change. Moving close to the third year since the viral #MeToo moment, we have to be thinking about how we make big strategic moves that are beyond individual takedowns”

The History of #MeToo in India

The #MeToo movement also reached the Hindi film industry – colloquially known as Bollywood – in 2018 when actress Tanushree Datta accused well-known actor, Nana Patekar.

Datta’s accusations emboldened other actresses to come forward including TV producer Vinita Nanda who accused veteran actor, Alok Nath of raping her twice. Her accusations have been validated with other female actresses who have worked with Nath earlier – Himani Shivpuri who also worked with him.

In an interview with Hindustan Times, Shivpuri realizes that Nath’s behaviour was like Dr. Jackyll and Mr. Hyde – a man who lived the image constructed by the media of a good man with traditional, respectful values – was false. He was known for erratic behaviour as Shivpuri recalls: “Whenever we shot in daytime, he would be mild and normal but after having liquor he used to be this Jekyll and Hyde person. He used to change completely. I heard from actresses that they had a tough time working with him.”

What has happened to the #MeToo movement since 2018? Has there been any progress with regards to gender-based violence?

Let’s be honest – the difficult, heartbreaking answer is no both in the film industry and India itself.

India continues to grapple with gender-based violence to this day. The rape and subsequent death of the twenty-six-year-old veterinary doctor in Shamshabad, near Hyderabad, which sparked a brief outrage in India has been forgotten in the national consciousness. I use the word ‘brief’ with caution because the accused rapists were killed in an “encounter” – a term that is used by the police. According to Jeffrey Gettleman and Hari Kumar from New York Times, the sudden killings of the accused men only managed to spark suspicion. While the officers were hailed as heroes, human rights activists such as Rajani Kumari who is the director of Center for Social Research called the killings a move towards vigilante justice system. Likewise, the death penalty of the Delhi rape case rapists is also being called into question and has been over the news these past few weeks.

Lata Jha of Live Mint listed eleven filmmakers who have now refused to work with the offenders. The list includes Nandita Das, Meghna Gulzar, and Kiran Rao. That is perhaps the most visible progress that the #MeToo movement in India has led to. But, I think this is where the progress comes to a screeching halt.

While America bore witness to the trial of Harvey Weinstein, (he still has an upcoming trial in Los Angeles) there are no high-profile trials taking place in a parallel manner in India. Instead, it seems that like business as usual for the accused men of the industry. The men who were accused are working and have neither been proven guilty nor acquitted for their crimes.

Jha reported that director Rajkumar Hirani (PK, 3 Idiots) who was keeping a low profile was still being recognized by the industry by being awarded ‘The Best Director In The Last 20 Years’ at the International Indian Film Academy (IIFA) Awards. Jha interestingly uses the word “the messy aftermath of the #MeToo movement” to describe the current circumstances in which Bollywood as an industry is coping with it — however — I would contend that this movement is not one that can end so cleanly and without leaving an impact.

Indeed, the #MeToo movement has been a boon in that it encourages women to speak up for themselves and feel that they can break the silence that is often found in rape narratives prior to 2017, which blamed the rape victim for the crime itself.

But, its implementation in each country has been different. In India, for example, the silence and shame around the rape/sexual assault victim continues to remain the same. Such ideologies continue to seep into the film industry as well. One anonymous film insider shared with Jha that “Bombay’s film industry is a coterie. There is no denying that people here are now scared because of the impact of #MeToo. They are more aware, and more mindful.” But she also states that there are many bigger names that have not been named in this movement.

Although there are recent upcoming films such as Anubhav Sinha’s Thappad (Slap) that are promoting a more assertive domestic abuse survivor, the industry still struggles to make sense of the representations of rape victims themselves.

For example, Ajay Bhal’s Section 375 that began innocently enough but ended with reinforcing the blame-the-rape-victim narrative in which she accuses a so-called innocent man in the industry for her own revenge — a tired narrative of the industry that too has failed to push the needle of the rape discourse during the time of #MeToo forward.

Instead, these sorts of representations are evidence of the regressive values that continue to shape parts of India that do not respect women rather reduce them to mere sexual objects. If women dare to speak, it is them who are at fault and must be punished for speaking up. Jha shares examples of women who have faced backlash because they chose to spoke about their experiences and accuse the men in public.

And it’s not just in Bollywood, in the South, Sripada was ousted for speaking up against Radha Ravi — president of South Indian Cine Television Artist Dubbing Union. Another Kannada actor Sruthi Hariharan alleged that co-star Arjun Sarbja had sexually assaulted her. Since then, her offers “have dried up drastically after allegations.” That being said, the women who are part of the Malayalam Film industry have continued to forge on to make sense and own the #MeToo movement.

The Women in Cinema Collective (WCC) held a press conference in Kerala in 2018 that sought to understand the ways in which misogyny and patriarchy systemically operate in Kerala’s film industry. As the women began the initiative, they were harassed by the press who began to make complaints of the discussion: “This is a gossip session!”, “Isn’t this just blackmail?” said many of the male reporters who were clearly unsettled by the oft-tabooed discussions that were taking place before their eyes.

The WCC had organized the event to address the failed leadership of Association of Malayalam Movie Artists (A.M.M.A) and how they addressed the sexual assault and abduction of a female actor by their industry’s megastar Dileep in February 2017. The WCC has been frustrated with A.M.M.A’s response to the case alleging that the organization neither suspended Dileep or took any actions to hold him accountable until he was arrested in July the same year.

The women, who were part of the WCC, also refused to address the organization formally by only referring to the them by their acronym which also sounds like “mother” in Malaylayam. The clash between WCC and A.M.M.A revealed that that the #MeToo movement in India is riddled with complexities and nuances. It is not as though the women who are prominent in the industry such as Revati are not pushing back against these systems of oppression, but, that being said, they are also facing a backlash from the industry that is not willing to reform and change the everyday routines to manage equality and the policy of no sexual harassment in this industry. These examples are from the South Indian film industry but these dynamics are shared by media and film industries world wide.

What does the Future Hold For #MeToo in India?

Just three weeks ago, there were new #MeToo allegations made against Ganesh Acharya — a famed choreographer who along with two other men were accused of assaulting a woman during a function of Indian Film and Television Choreographers Association (IFTCA) held in Andheri, Mumbai. In response to this allegation, Acharya called her charges “false and baseless” and said that she was perhaps with the termination of her membership in IFTCA but denied these charges.

What will become of this case? Will there be a trial? Why is the burden of proving rape on the shoulders of the victim? – The answers to these questions remain unanswered.

We need to see the #MeToo movement with the lens that it is the movement that is not only for the privileged and rich who are part of the Indian film industry but it is a movement that is designed to empower young and old women all around in India. The #MeToo movement requires the survivor of the assault/rape to speak up and share her story.

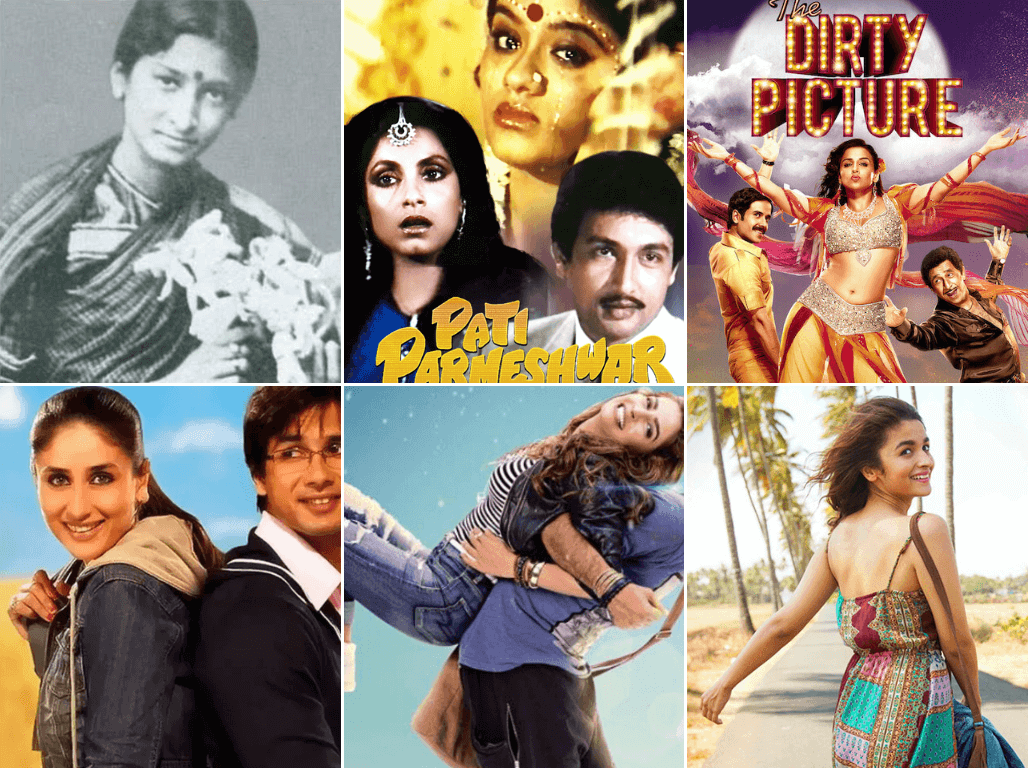

While in the Western countries, it is seen as an empowering gesture. This same gesture continues to be regarded as a taboo in India. If a rape victim speaks, she is threatened or shamed. The same remains for the women in the film industry who fear that if they choose to voice their experience, they will be shunned from the industry. In a powerful scene in Imtiaz Ali’s Highway (2014), we saw that Veera (Alia Bhatt) had the courage to share her experience of childhood sexual abuse in front of her relative who was responsible for it. The film’s rendition, unfortunately, only remains an utopic fantasy for everyday girls and women to aspire to have the courage to speak about.

And that’s where the #MeToo movement stands in India — there is hope but until we respect and accept the survivors of gender-based violence, this fantasy of a young girl having the courage to speak up will remain a fantasy — not the truth she carries with herself.

Nidhi Shrivastava

Author

Nidhi Shrivastava (@shnidhi) is a Ph.D. candidate in the English department at Western University and works as an adjunct professor in at Sacred Heart University. She holds double masters in South Asian Studies and Women's Studies. Her research focuses on Hindi film cinema, censorship, the figure o...