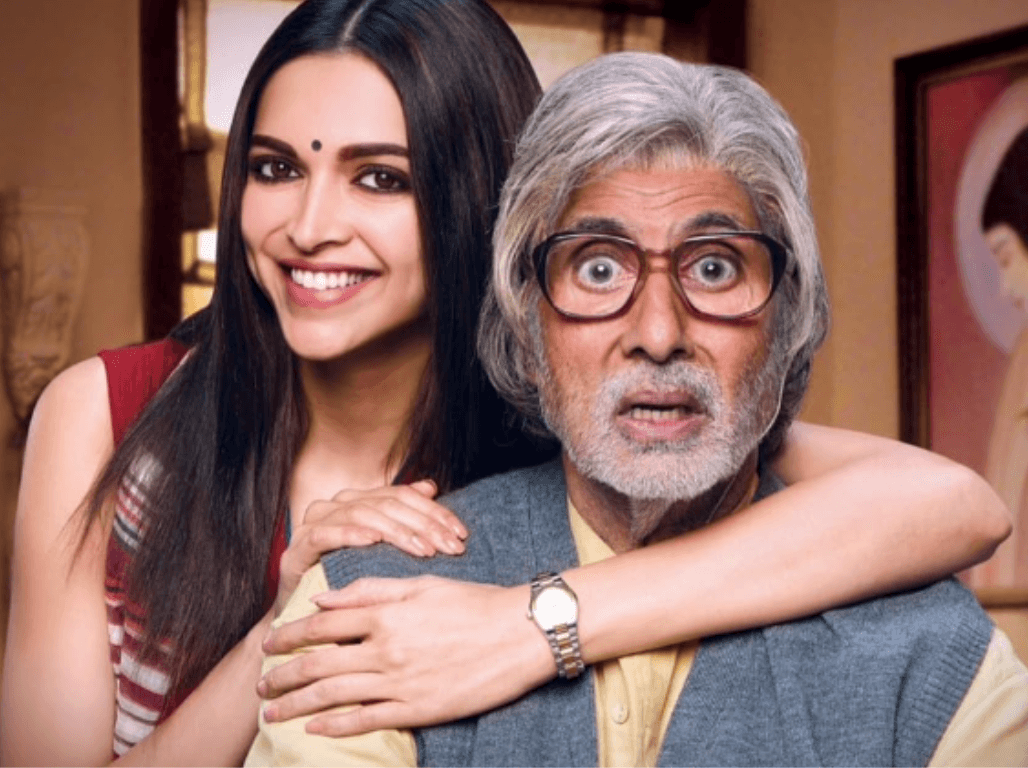

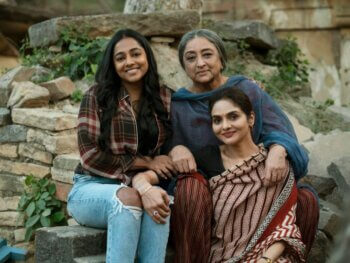

TIFF 2023: Deepa Mehta and Sirat Taneja Share Why ‘I Am Sirat’ Is The Transgender Story To Be Told

Entertainment Oct 27, 2023

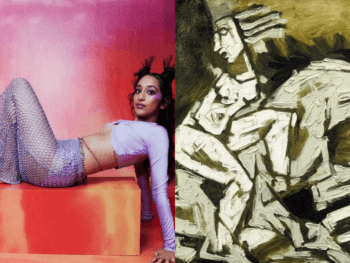

Canadian legend Deepa Mehta and her co-director/subject Sirat Taneja tell us about their poignant, intimate new documentary I Am Sirat, tracking the latter’s journey as a transgender woman forced by familial expectations to lead a double life.

From her Oscar-nominated Elements trilogy to Salman Rushdie adaptation Midnight’s Children to loopy crime thriller Beeba Boys, writer-director Deepa Mehta has always been what you might call a cinematic chameleon. For her latest creative shift, the iconic Canadian filmmaker (whose movies have frequently found their way to TIFF over the years) dips back into documentaries to co-direct an intimate account of the transgender experience in India. Her co-director? Sirat Taneja, who is also the film’s subject.

Sirat is a trans woman living in New Delhi, and the very particular circumstances of her life will no doubt have a universal resonance. In many facets of her existence — with friends, at her job with the Government of India, on her popular social media feeds — Sirat is thriving, free to be her authentic self. But at home, living with and dutifully caring for her aging, very traditional mother, she must revert to “he,” as mom cannot abide her child’s true identity.

Shot largely by Sirat herself, on her very own iPhone, I Am Sirat offers an in-depth portrait of its title character — the joys and struggles of her day-to-day — as well as the duality of a country that is, as the official TIFF synopsis puts it, “caught between tradition and progress.”

During the festival this past September, Anokhi Life sat down with both Deepa Mehta and Sirat Taneja to unpack the film.

Matthew Currie: By the time all was said and done, did you make the film you set out to make? Or did you end up making something different as the creative process evolved?

Deepa Mehta: I think it’s more or less the same ballpark. Maybe if you’re shooting for a long period of time, and you’re discovering it as you go, and then you’re editing for years sometimes, then things change. But we started shooting in November and we finished in July, and we knew pretty much what we wanted to do, which was: Sirat wanted to record her life as she saw it, and it is what it is. It wasn’t a huge amount of footage. We were doing it on our cellphones. So it was very controlled right from the beginning. There were a few times we did things that were not expected. But it still turned out to be pretty much what we thought we wanted to do. In the editing process, of course, things shift and some scenes become longer. But the whole trajectory of it has always been Sirat’s life and how she sees her life, what her dilemma in her life is, and how she deals with it.

Sirat Taneja: When we said that this is the way we’ll do it, that I would control my own narrative, that I would be telling my own story of my own life in my own terms, I thought about it very carefully. It wasn’t like I [just] said, “OK, I’m going to do it.” I thought about every aspect of what I wanted to reveal, and that was great. It was a thoughtful process. The way it turned out . . . it’s the experience of doing it that I’m very pleased with. How it will be received, I don’t know . . . but I did it with a pure heart.

MC: For you, Deepa, it must have been a fairly unique creative process — directing with another person, another artist . . .

DM: It’s not about directing. It’s about the collaboration of Sirat telling her life story, and while she’s telling her life story, I’m filming her telling her life story. So nobody said, “Action!” and “Cut!” [Laughs] We didn’t get into that. I feel I am a facilitator. She’s telling her life story, and while she’s telling her life story, I am shooting her telling her life story, shooting herself. It’s a different kind of movie.

ST: No retakes!

DM: Yes, no retakes, no camera person, no sound [person], nothing . . . It was wonderful.

MC: Did you find the process of filming largely on an iPhone just offered, literally, a different lens to tell a story than you’d experienced before?

DM: The whole thing was something I’d never dealt with before. But the most fascinating thing about this whole process was Sirat opening a door of perception for me. I go to Delhi every two or three months, but the Delhi I saw through Sirat’s eyes was a completely different Delhi — and also her lived experience. It’s nothing like I’ve done before. But I think that every film that I’ve done is different; I am exploring something different and unique for me. I don’t do anything if I’m not interested in it, and I was fascinated and honoured to be there while Sirat told her story.

MC: That’s interesting, because looking at your career, you’ve really never stagnated in one type of film, one mode of expression for very long. Do you feel like you’re always looking for new modes of storytelling?

DM: Actually, I’m only interested in one story. In all my films, there’s only one story. And that story is basically about the duality of our lives, and where do we belong? In Sirat’s case, what intrigued me as somebody who was looking on while she was telling her story, is the duality of Sirat’s life — duty to Sirat’s mother vs. her self-determination. She wants to be Sirat, but she’s a dutiful child. So, for her mother, she is the son that her mother wants her to be. It is not what she wants, but she does that. So, duty vs. self-determination: Where does one belong? We talked about that for a long time. What happens to her own life? When do we become selfish and when do we become self-determined? It’s something that actually has been, as I look back, a part of all the stories that I’ve told. It’s just a different way of looking at it.

MC: Sirat, you have a literal lifetime of experience with your own family. But then once you actually put this film together, and you get to look at your family from the outside, did you come away with a different perspective on your mother and your relationship with your mother?

ST: My mother is aware of my true nature — that I am Sirat. But my mother’s fear is what society thinks about the person that she gave birth to — which is, in her mind, a son. How will the society accept her? I am worried about that. But I know in my heart that sooner or later my mother will accept me — I hope and cross my fingers. And maybe the film will help her do that . . . I really hope that a lot of people will see it and realize the metaphor is: the impossible is possible.

MC: What exactly is the value of exploring larger societal and cultural issues, like trans rights, through such a deeply personal story like this?

DM: I think, unless it’s deeply personal, why make a documentary? Aren’t documentaries supposed to be personal? I think it’s amazingly courageous putting your life out there and talking about the duality. What Sirat has said to me in the past is that all of us — not just a trans woman — we are all looking for a place that we can call “home.” And for her, the film is about finding that home and showing people that we can do it. We can do it with optimism . . . I hope that people might feel [about this story] the way I did: that life can be tough, but Sirat is an inspiration.

Main Image Photo Credit: www.tiff.net

Matthew Currie

Author

A long-standing entertainment journalist, Currie is a graduate of the Professional Writing program at Toronto’s York University. He has spent the past number of years working as a freelancer for ANOKHI and for diverse publications such as Sharp, TV Week, CAA’s Westworld and BC Business. Currie ...