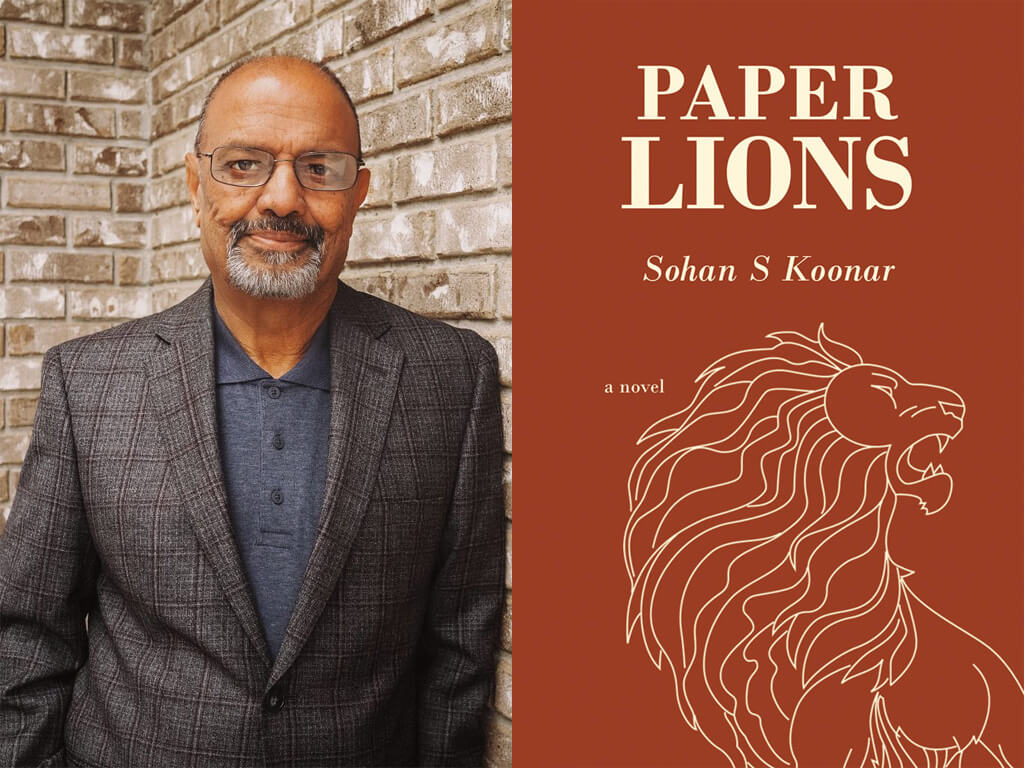

Sohan S. Koonar Tackles The Whitewashing Of Sikh History In His Book “Paper Lions”

Entertainment Feb 25, 2020

Armed with his second novel Paper Lions (Mawenzi House Publishers Ltd.), Sohan S. Koonar shared with us his perspective on the inadequate Sikh representation in English literature, his inspiration behind his literary project and why this novel is important reading for the younger second and third-generation Sikh Canadians.

Paper Lions is an epic multi-generational novel that explores the lives of Bikram, Basanti, Ajit, and their respective families as they live through the monumental moments of Indian history from pre-independence to the 1960s.

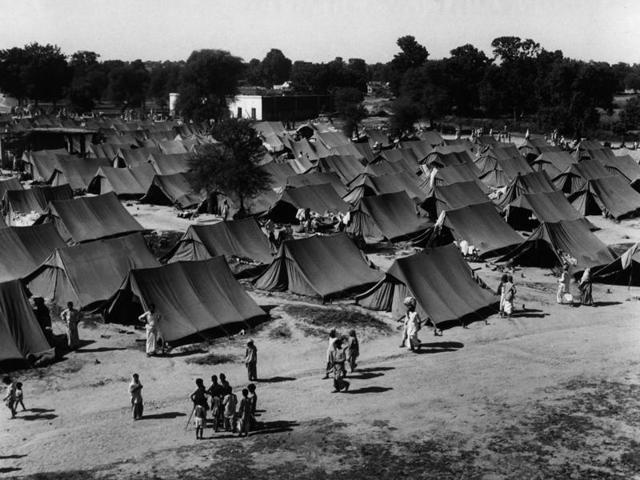

Koonar’s novel underscores an important history of the 1947 Partition and the collective shared trauma that exists between the Indian sub-continent and the Indian diaspora. This key feature of the novel arguably makes this novel is a must-read for the younger generations in North America of South Asian descent but also, it is a journey for North Americans as well to have an opportunity to familiarize themselves with the history of Indian sub-continent which is often overlooked in the memorialization of the Second World War.

Koonar’s novel also gives us readers a rare insight into a nomadic tribe called the Bajigars (also known as Bazigars or Goaars) who are an essential part of the social fabric in Punjab but have remained invisible in modern Indian history.

Nidhi Shrivastava: I wanted to begin with what was the inspiration behind writing the novel?

Sohan S. Koonar: I will tell you a story. I was at an international writer’s conference and I met Naomi Ragen. She is an orthodox Jewish woman from New York and she only writes about the orthodox Jewish people. She had written fourteen novels. I was sitting beside her at lunch and she asked me what my faith was. I told her I was a Sikh, and she said, ‘Sohan, there is nothing that I can find about Sikhs in English literature. I am very curious about the people who wear turbans and I was a little bit surprised because there wasn’t really much in English literature about Sikhs. Why don’t you write what you know — write about your people.’ So, that was the main inspiration behind the novel.

I know these stories, I grew up with these stories. I grew up in Punjab and I am Punjabi and I do read a lot of Indian authors such as Salman Rushdie, Rohinton Mistry, Jhumpa Lahiri, and all. They primarily wrote about stories that are based in large, urban centres like Delhi, Bombay, Calcutta, and so on. They don’t really portray the real India — the majority of India that is in the villages — rural India. I thought I will try to construct something about Punjab and after talking to different people, I thought I would write historical fiction but more about the old Punjab and then turning to modern-day Punjab.

NS: Downton Abbey has been a great television series that highlights the history of England and experiences of the same family that witness and are part of the momentous events that shape the modern United Kingdom today, how did it play a role in the formatting of the time frame of the novel?

SSK: I had not watched Downton Abbey while writing the novel. When my literary agent read the novel, he said this was the “Downton Abbey of India” because the novel follows significant events in the history of India and Punjab and the Partition being the most significant. At the time I was writing it, I didn’t realize that somebody would one day describe it as the Downton Abbey of India or Punjab.

NS: I noticed that the 1947 Partition is an important part of the overall narrative of the novel. I was wondering if you could elaborate further on why you wanted to highlight the Partition and it’s significance?

SSK: Partition as a muse will always exist for writers of the sub-continent and for those who have carried it in some way beyond borders. Millions [of people] died during the Partition. It is still a very cataclysmic event that continues to shape the psyche, the Indo-Pakistani relationship, and the inter-faith relationship in India to this day. It lingers in our psyche and in our literature. Our literature and films are filled with Partition stories. We cannot whitewash our history.

But, as you and I know, even Indians have forgotten about it. And particularly, our second, third, fourth generation Indians that are growing up in North America. They don’t have a clue about it. So, I thought if I write a work of historical fiction then at least I am writing it for my own children who were born and raised in Canada, my grandchildren and maybe their children. I could teach some history of India, Punjab and Sikhs in an interesting way. People would read and say that I was not only entertained but I also learned something.

NS: In an interview with The Sunday Guardian, you mention that Paper Lions has the only representation of the Bajigar in English literature. Why was it important for you to draw attention to the lives and narratives of the Bajigars?

SSK: Let me give you a little background of Bajigars. The Bajigars have claimed that their roots originate from the Rajputs that hailed from Rajasthan. Rajasthan was the land of Kings. The Rajputs were pretty good warriors. There are some tales that have shaped their origins as nomads. The Bajigar generals [Jamla and Patti] faced the Moghul king Akbar the Great. To win them over, Akbar offered to marry one of their daughters. But they refused, which led Akbar to threaten war against them. They knew that they had no chance against the army so, they left. They abandoned their lives in Rajasthan and began nomadic lives.

Because they were athletic, warrior people, they developed different strategies to survive and one of the strategies was calisthenics. They would go into villages and they would give circus-type performances. They would show human pyramids, bending metal, breaking wood, and jumping. It is called baaji – display of human athletics and that’s why they were called Bajigars. Some of the members of the tribe became Naths, who would hold theatres, song and dance, and they became nomads and never settled down.

To this day, they continue to wander around India. And, Punjab has a fairly large population of Bajigars. They are Rajput Nomads and after independence, Nehru decided that everyone should be given a place to settle down. They were given land in Punjab. The Bajigars then settled and after three, four generations, have settled into the Punjabi society. Now, they are an important part of Punjabi society. A lot of them have adopted Sikhism and they still have musical talents. A lot of Punjabi musicians are descendants of Bajigars.

Punjab is diverse and Bajigar is an important part of Punjab. When I was growing up, they were an exotic tribe and living off the land. And, then I thought 1 in 5 Punjabis are Bajigars. I had admiration and fascination with ancient tribal people. Here, I had a chance to preserve Indian tribal history in Punjab. And I searched and met a tribal oral historian who educated me in the tribal ways, culture, traditions, and their history, and how they were integrating them into the Indian society at large. I was able to develop the Bajigar clan as a credible storyline and that’s how I developed Basanti, the female protagonist of the novel. Part of the reason why my book got published was that the editors were fascinated with Basanti. If I accomplished anything by writing this book, I think of Basanti’s creation as a proud achievement.

Main Image Photo Credit: Sohan S. Koonar, Mawenzi House Publishers Ltd.

Nidhi Shrivastava

Author

Nidhi Shrivastava (@shnidhi) is a Ph.D. candidate in the English department at Western University and works as an adjunct professor in at Sacred Heart University. She holds double masters in South Asian Studies and Women's Studies. Her research focuses on Hindi film cinema, censorship, the figure o...