The Team Behind “Emergence: Out Of The Shadows” Tell Us Why Parents Of LGBTQ+ Kids Need To Share Their Stories Too

Entertainment Oct 13, 2021

Emergence: Out Of The Shadows shares three stories of LGBTQ+ community with one important element: the parent’s POV. We chat with producer Alex Sangha and director Vinay Giridhar about the power of this medium, how it’s important to shed light on parents who are accepting of their children after they come out, and to give hope to people in a potentially very dark situation.

The new documentary Emergence: Out of the Shadows tells the stories of three British Columbians and their families who have grappled with and overcome the taboo of being LGBTQ+ in the Punjabi Sikh community.

Currently making the rounds on the festival circuit, Emergence: Out of the Shadows takes us inside the lives of three South Asian members of Metro Vancouver’s LGBTQ+ community — Jag, Kayden and Alex. Representing a diverse array of experiences, each recalls his or her path to first accepting their sexuality and then coming out within a traditional Punjabi Sikh community where the fear of rejection, harassment and worse forces many in their position to keep their true self hidden.

In particular, the film hones in on each subject’s relationship with their parents, several of whom were quick to accept and support their children after they came out. Here, these moms and dads also recount their journey toward understanding and acceptance.

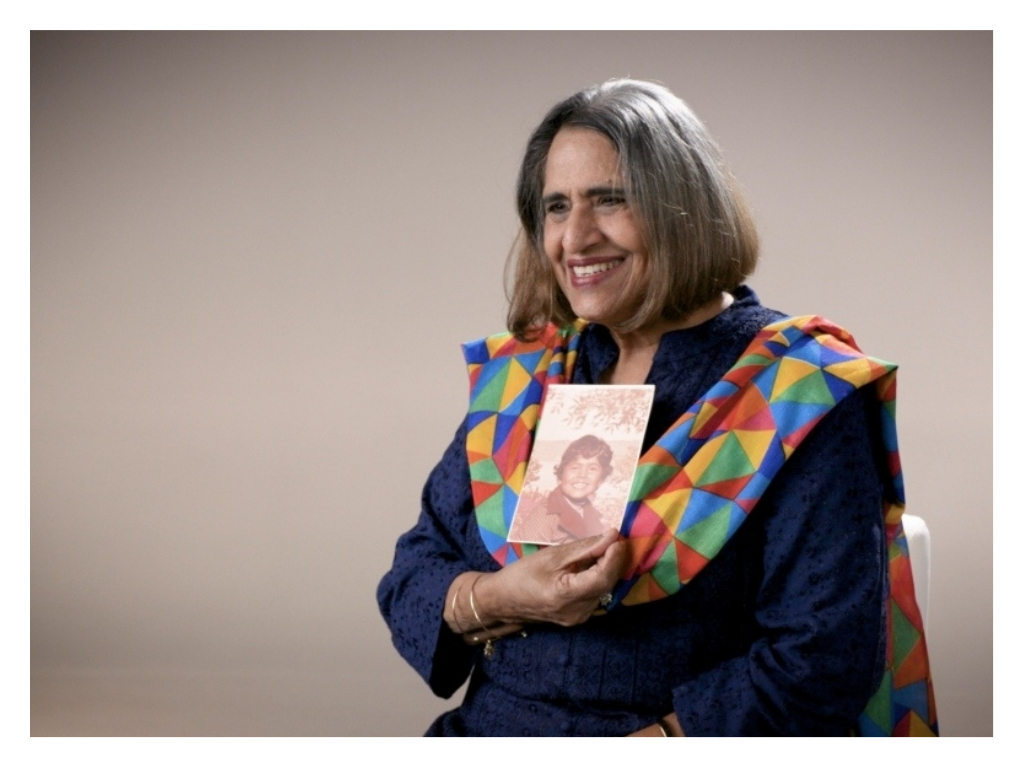

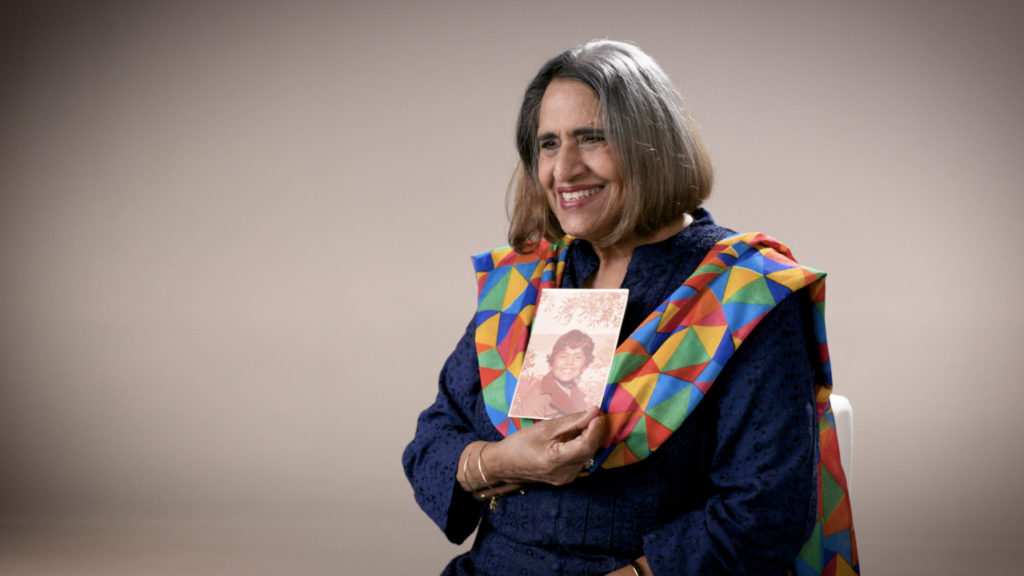

Appearing in Emergence alongside his mother, the aforementioned Alex Sangha is also the doc’s producer. He’s a social worker and founder of Sher Vancouver — a non-profit which offers support for the LGBTQ+ community and their loved ones. Each of the primary interviewees is also a member of the Sher family.

Recently, we spoke with Mr. Sangha and the film’s director, Vinay Giridhar, about crafting this unflinching yet hopeful look at an underrepresented struggle.

Matthew Currie: Tell us about the origins of Emergence.

Alex Sangha: What happened was, we had this young man named Kayden contact my non-profit, Sher Vancouver [several years ago]. He was homeless, he was helpless, his immigration status was in limbo . . . I thought, “It would be so important to share Kayden’s story.” He was the impetus for the film. Because I said, “We don’t want other kids in our community to be rejected. We wanted to create awareness, we wanted to create education.”

And when we were thinking about how to craft the film and what components need to go in the film, we looked at the members of Sher Vancouver and the stories. When we were narrowing down the interview subjects, we were like, “We need the parents.” The film is not going to have the impact if it doesn’t have the parents. Because really, it’s the parents that have the power, and if you really want to create awareness and education around what happened to Kayden, if you don’t want that to happen again, you’ve really got to educate the families involved. So we had my mom, who was willing to be in the film, and that is sort of how I, by default, got into the film. Even though I was the producer, it was up to Vinay to decide if he really wanted to cast me [laughs].

Then, we wanted a gender balance, we wanted a female perspective, and so Jag ended up in the film. So these three storylines ended up in the film. We felt it was a good fit.

MC: These are three very distinct stories, three distinct experiences that you’re weaving together here . . .

AS: The thing which I’m glad Vinay decided to do was, he felt it was important for all three stories — including Kayden — to have redemption. Because we didn’t want young kids in high school who were coming out or were unsure about their sexuality to feel that if you come out to your family or something happens, that your life is going to be miserable and hopeless and you have no future. We wanted to give hope, we wanted to give redemption and we wanted to end on a high note . . . That’s why it’s called Out of the Shadows, because we are dealing with a really dark film for a huge chunk of it, before it gets into a much lighter, more positive ending.

MC: Vinay, what was your strategy for getting your subjects to open up about some of these very painful, very personal things?

Vinay Giridhar: It was a blessing that I’ve been volunteering and working with Sher Vancouver for a long time now, so I’m very familiar with the people that I interviewed. I’ve built a relationship with them over the years, and they kind of trusted me. I feel really honoured that they actually opened their hearts to me. A stranger coming in asking questions probably won’t have the same answers. It’s probably because I knew Alex’s mom for years and years; and Alex for a long time, and Jag. That really made my work a little easier.

And then it was really interesting for me to watch how little they knew about each other’s journeys. Even though they live under the same roof, the mom and the son. When it comes to Indian culture, South Asian culture, when it comes to sex and sexuality, it’s considered a taboo and people don’t talk about it. Even though we say that families are close and we care about each other and everything, when it comes to these kind of topics, there’s barely any conversation going on in the houses.

MC: That shocking one for me on that note was Jag and her brother, siblings who are both LGBTQ+. But when they find out that they share this sort of secret, even they can’t open up to each other and really discuss it.

VG: They were both born and brought up here, they have a different worldview from me, who comes from a different country [India] and lived a different life over there. I would have a huge issue talking to somebody about something like this. But they should be able to, right? That was really surprising.

AS: It just shows you how much cultural pressure there is. There’s so much pressure in the South Asian community to get married and have children, to not embarrass the community, to not shame your family, to live with your family forever, to take care of your elders. In a way, when you accept a gay child, you are getting ready to prepare to accept rejection from everyone else in your community. And not every parent wants to do that.

Over the last 12-13 years since I founded Sher Vancouver, so many young brown kids, South Asian kids, when people find out they’re gay, maybe they’re not rejected like Kayden, but they’re disinherited; families don’t pay for their school, they’re alienated and bullied and they’re marginalized within their families, they’re pressured into arranged marriages. Could you imagine being a straight guy and forced into an arranged marriage with a gay guy? This is literally what you’re asking these people to do. And it’s very sad . . . This is why we need to accept gay people and embrace them and treat them with respect and dignity and equality.

MC: Alex, what was it like for you to look back on those dark times in your own life?

AS: Well, you know, Vinay never told me the questions he was going to ask me — so he put me on the spot during this whole interview process. Everything that came out was raw, was natural, was authentic. And it was very, kind of, traumatizing for me. Because I didn’t realize how emotionally, psychologically abused I was as a teenager and a child. I’m 49 now and I’d forgot about a lot of this stuff. It was really difficult, but at the same time, the film was very therapeutic and it brought closure for me.

But you know what was amazing about the film: my whole life I thought my mom loved me and accepted me for being gay, and that she had no issues. But when I watched the film, it was a real eye-opener for me, because for the first time, I got to see my mom and her struggle with accepting her gay son. And I was like, “Oh my God, it wasn’t easy for her.” In her whole life, no one asked my mom her feelings, her emotions around her son being gay. And she never had that opportunity to get it out of her system and to discuss it in a cultural context that would be safe.

MC: What do you think is the power of representation, in making a film about a life experience that still isn’t all that commonly seen onscreen?

AS: Many members of the cast and crew are queer, South Asian; we tried to provide a lot of opportunities for people so that the film had integrity, so it was authentic. There’s a saying called “Nothing about us without us.” Which means, if you’re going to do a story about queer people or South Asian people, well then they need to share their stories. We don’t need all these experts or specialists theorizing about what these people should or shouldn’t do, especially from the western world, based on all the history of colonialism and discrimination and oppression that have been inflicted on colonies and countries and people of colour around the world . . .

. . . I was talking to Moving Images, my distributor for this film, and [my contact] said, “You know what? You’re the only South Asian film listed under ‘Documentaries’ on our entire catalogue.” [Laughs] And they have, like, thousands of films. And she said, “There’s not a lot of body of work or content about gay Punjabi Sikh families. It’s just not there. This is really pioneering work.”

VG: When we started discussing making a film like Emergence, one thing that consistently came from everybody involved was, “We need to make a movie that at least saves one life, or makes somebody feel like they are not alone.” It was very important for us to send that message out to the people who are suffering by themselves. Representation is crucial in this world; it is crucial for people of colour, people of various genders and orientations, so that they can see on the screen that there are other people like them. They are not alone.

Main Image Photo Credit: Sher Vancouver

Matthew Currie

Author

A long-standing entertainment journalist, Currie is a graduate of the Professional Writing program at Toronto’s York University. He has spent the past number of years working as a freelancer for ANOKHI and for diverse publications such as Sharp, TV Week, CAA’s Westworld and BC Business. Currie ...