‘Because We Are Girls’ Doc Explores The Trauma Of Being Assaulted By A Male Relative

Entertainment Nov 22, 2019

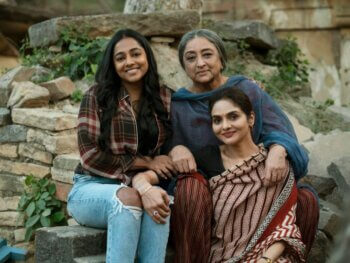

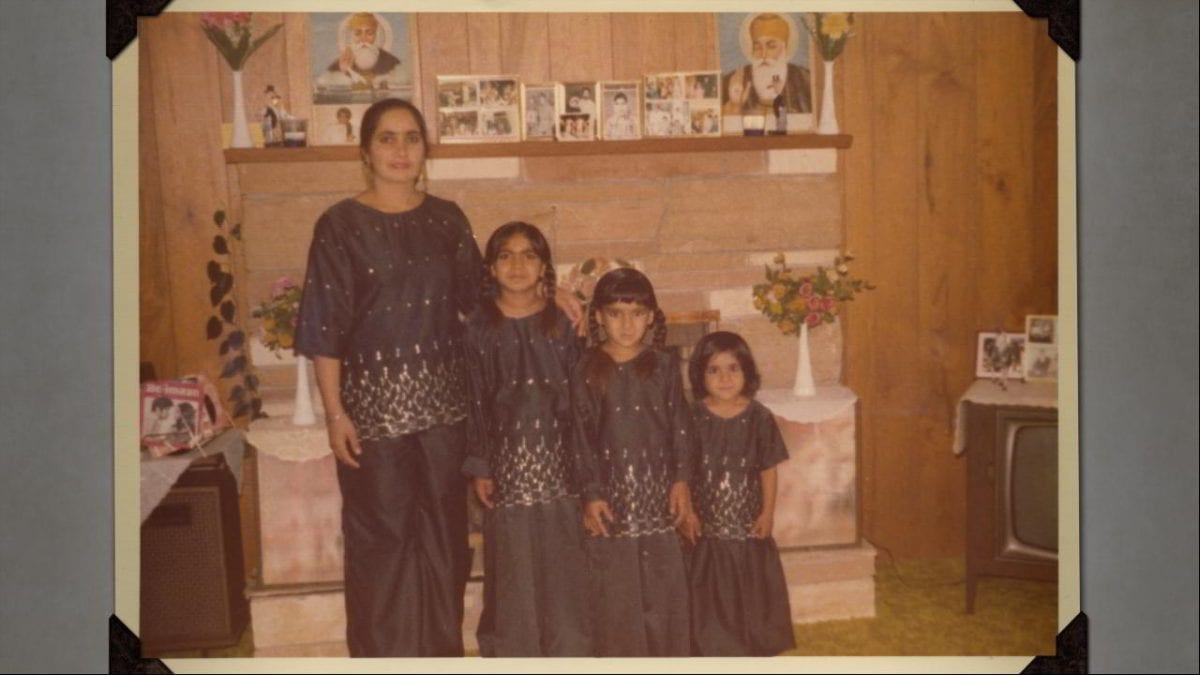

When director Baljit Sangra was looking to film her next documentary the subject matter was close to home. In Because We Are Girls, she shares her journey of telling the harrowing story of her friend’s trauma of childhood sexual assault … by an older male relative.

Because We Are Girls is a story familiar to many. A devastating secret, simmering under the surface for years, breaks loose in a community barely equipped to deal with the aftermath.

A story of childhood sexual assault.

For the director Baljit Sangra, the connection ran deeper.

“One of the protagonists in the film — Jeeti Pooni — she’s a friend of mine,” said Sangra.

Pooni had approached her with the idea of making a documentary on sexual abuse in the South Asian community. “I said that would be an amazing topic but what would my access be like?” explained Sangra. “That’s when she disclosed that she and her sisters were survivors of sexual abuse.”

Their sexual abuser? An older male relative.

He was “someone my parents trusted,” said Pooni, in the film. “The day that man came into our house, we were told basically, ‘this is your brother. You respect him. You call him paaji.’”

The abuse had carried on for years, under the noses of their brother, parents and other relatives in the house, without anyone ever finding out. “I knew it was happening in the house, but I didn’t know what to do about it,” said Salakshani Pooni, Jeeti’s older sister. She and their youngest sister Kira were also abused by the cousin.

It had been years since the assaults happened, by the time Jeeti had brought Sangra into the fold. “She told me they went to the police,” said Sangra. Pooni continued to fill Sangra in on the details of the investigation and by the time the case arrived at court. Sangra knew the story was going to have a “profound impact.” “The film would have been strong even without the court thread but that gave it a real momentum and a real tension,” she added.

It helped that Sangra has years of experience producing documentaries on Vancouver’s South Asian community. Her last film, ‘Warrior Boyz‘, made headlines for its in-depth look into gang violence, focusing on the stories of young South Asian men looking to carve a reputation for themselves. “I’m trying to humanize it,” she told Georgia Straight, “to put a face to a kid and what they’re going through.”

Yet, Sangra said it was her personal relationship with Jeeti and their shared cultural background that helped her win the family’s trust in the making of the documentary. “I’m South Asian and I’m a friend,” she said. “So it weighed heavily on my shoulders too, how the story was going to be told.”

“I understood so much about why they had to keep it a secret, from the patriarchal system and just on a lot of levels,” she said. “I also grew up in the same culture with the same social values.

The documentary, she said, is three years in the making. “We did it really slowly,” said Sangra. “I started the process with context — the family’s immigration to Canada, sponsoring their relatives, I think that story needed to be told too.”

The film’s narrative is poignant, yet careful in pointing fingers. It dives into the lives of each family member, starting with the parents’ arranged marriage in India at the age of 18, Salakshana’s toxic marriage, and what the sisters felt like to come second to the birth of their youngest sibling — the first and only son in the family.

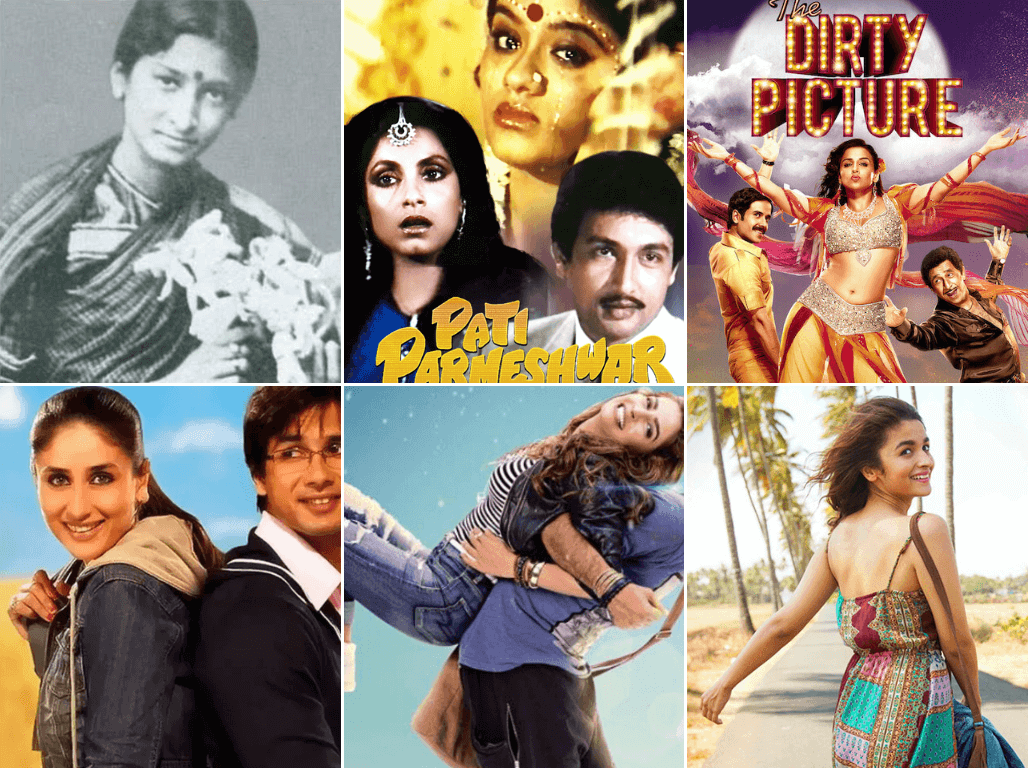

Clips from old-time Bollywood narratives are weaved in throughout the film, to an increasingly disturbing effect, highlighting the message of obedience and chastity fed to young South Asian girls — and the silence that ensues if the codes are broken.

“You can’t go talking to anybody about it,” says Jeeti in the film. “You can’t go tell your sister, or your mom or whatever. Bad girls in those times got shipped off to India.”

“We bottle it up, sweep it under the carpet or don’t talk about it but it does have an impact and you see that in the family,” said Sangra. “It impacts your relationships, your mental health, how you are with your kids, your parents, everything.”

Which is what makes documentaries like hers all the more important. “At a panel after a screening, there was a senior woman who shared her story of what it was like when her daughter came forward,” said Sangra. “So that was super powerful to get those kind of class-generational conversations and unpack that intergenerational trauma.”

The film also gives viewers a glimpse into the emotional toll of going to trial, especially on the sisters. “It took them three years to get through (the court process), which is pretty daunting,” said Sangra. “So they really had to support and rally around each other.”

While we never see what went on in the courtroom, Sangra does include scenes of the sisters either about to enter, or leaving the room with their lawyer. “Only one percent of women make it to where we’ve made it,” Jeeti tells Salakshana and Kira, at the very beginning of the documentary. “Now it’s that moment where we go into verdict and whatever happens, happens.”

“They didn’t do things separately,” said Sangra. “If one had to testify, the other two always came up as well, they were always there for each other.”

As of now, the court case remains unresolved. Last year, the Supreme Court of British Columbia found the accused guilty of four out of six charges. The accused has since filed a Jordan application, alleging that his charter right to be tried within a reasonable time was compromised.

Verdict or not, the film has done what Sangra hoped it would do — start conversations.”For a lot of people, it’s a big cathartic release,” she said.”People have shared that this something they’ve gone through and that they’re finally able to talk about it with parents. Senior women hug me with tears in their eyes. We’re seeing guys come forward and sharing their experiences. “

“To be a part of this journey and to know it’s going to have an impact — it’s really powerful,” she added.

The documentary is currently in the festival circuit having premiered at the Hot Docs Canadian International Documentary Festival in Toronto and at the Doxa film festival in Vancouver.

Main Image Photo Credit: Project Four.

Devika Desai

Author

Devika (@DevikaDesai1) has a Masters in Journalism from Ryerson University. She's currently a web producer for the National Post. She has also interned at MidDay, a Mumbai-based tabloid. In her free time, she loves to read, work out once every blue moon and ask strangers if she can pet their dogs.