TIFF 2018: Director Nandita Das Shares Her Journey And Her Biopic “Manto”

Entertainment Sep 28, 2018

We went one-on-one with director Nandita Das at the Toronto International Film Festival, where we discussed her new biopic Manto and her role in the Share Her Journey rally for gender equality in the film industry.

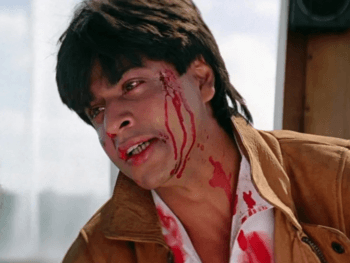

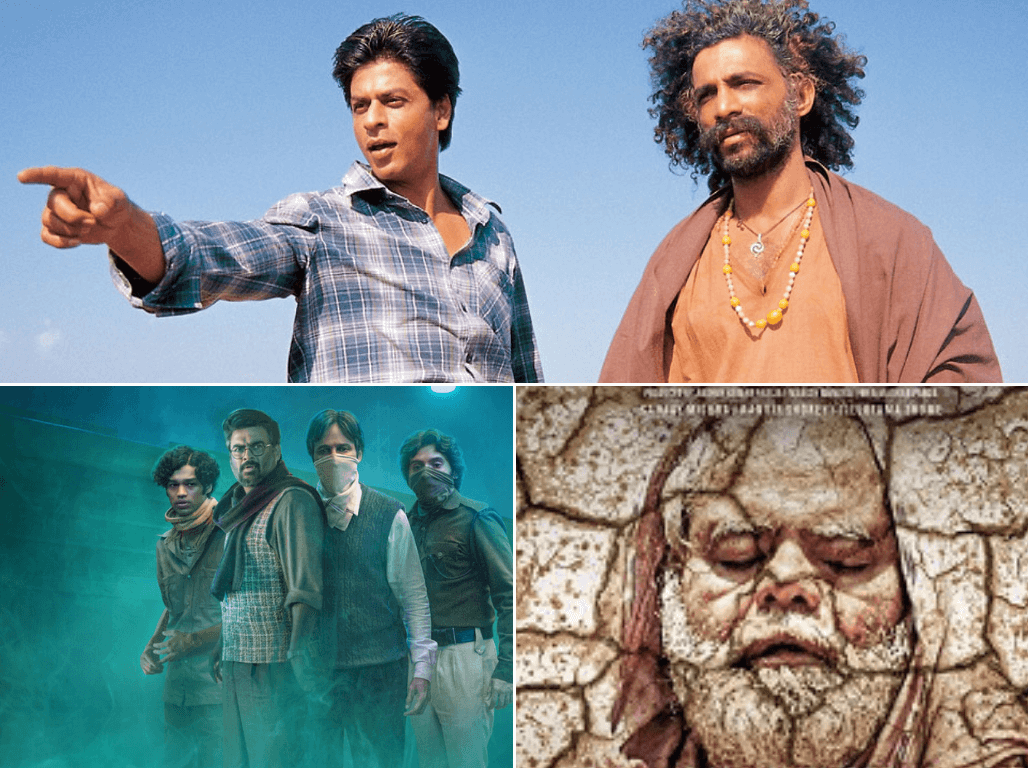

Ten years after bringing her directorial debut Firaaq to TIFF, actress-turned-writer-director Nandita Das was back in Toronto with her sophomore effort Manto, a drama centred on the often-tragic life and vital legacy of Urdu writer Saadat Hasan Manto, starring her old friend Nawazuddin Siddiqui. A prolific writer of short stories and essays, Manto trained an unflinching eye on the dark corners of post-independence, post-Partition life, and his commitment to portraying truth — no matter how brutal, explicit or unsavoury — led him to a life of frequent persecution, as well as alcoholism, a strained relationship with his wife Safiya (Rasika Dugal) and young children, and ultimately an early grave at the age of 42.

While she was in town, Das was also invited to speak at TIFF’s Share Her Journey rally, promoting gender parity in the film industry. During the festival, I got the opportunity to sit down with her and discuss both the vital importance of the Share Her Journey movement and the enduring relevance of a fearless iconoclast like Manto.

Matthew Currie: You’ve been coming to TIFF for years, but you got a unique opportunity this time, speaking at the Share Her Journey rally.

Nandita Das: Yeah, that was very special. Even in Cannes, where we had our world premiere for Manto, they had these 82 women walk the red carpet, and I was one of them. That was a very moving experience as well. By the end, women were hugging each other, bursting into tears with just this collective will to want to change things. And then here again, I saw that kind of energy in the crowd. They were standing for two-and-a-half hours listening to all of us. I think it’s a very important initiative; I’m glad that it [started] even before the Harvey Weinstein story; it acknowledges that this existed before and whether we like it or not, it’s going to continue for a long time unless we [take action].

I’ve kind of had a difficult relationship with this “woman director” tag. You’re like, “What the hell? I’m just a director.” But lately, with all of this happening, I’ve also been thinking about it and owning that label more easily. Because we are demanding that there’s more gender parity in the film world, and until there is a level playing field, we will have to own up and say, “Yes, I am a woman director and I want many more such women directors.”

MC: It’s tough to fight that inequality when it’s so deeply seated in an institution.

ND: Yeah, and for decades. Even in India, it’s a very male-dominated industry. Often in the team, people are constantly calling me “Sir.” Like, “Sir . . . oh, Madam.” People are not used to a woman helming a project. I’m standing with my cinematographer and we are talking and people are looking at him, and I have to keep reminding, like, “Hello, I am the director” [laughs]. But things are changing. A lot more younger female directors are coming into the field. It’s still a miniscule percentage, but at least it’s happening.

MC: What attracted you to the story of Manto, this iconoclast writer?

ND: I had read Manto in college, mostly short stories. It was only in 2012, when it was a centennial celebration, that a lot of people started writing about him, and his essays got translated. When I started reading his essays, I thought, “Wow, here is a man who is equally fascinating as his stories are.” And I felt that by telling his story and what was the struggle and what was the strength needed to follow the kind of convictions he had about speaking truth, I could also respond to what’s going on today, where artists and writers are self-censoring and are not wanting to “offend” anyone. Or there are self-proclaimed custodians of culture telling us what we should be making, which I experienced personally with Fire, which was attacked when it came out in India, and with Water, for which I shaved my head, and the actors couldn’t be part of the film later because we were attacked on the first day of the shoot.

I think it is a time [to] talk about freedom of expression and see role models like Manto, who fought to the very end; in his worst of times, he didn’t stop. He continued to be prolific and continued to tell things as they are. I think that’s very inspirational — and yet, he’s not somebody I’ve put on a pedestal. He’s very fallible. He’s a man of contradictions, and that makes him, in a way, more human and attainable.

MC: One of the most interesting things about the film is the way Manto’s stories, or ideas for stories, are woven into the narrative of his life, in a way that just all of a sudden puts the viewer inside one of his stories, and it takes you a moment to realize you’ve left his real life and stumbled into one of his stories. How did you conceive of that?

ND: Right from the beginning, I felt, it’s like if you were doing a film on a musician but not hearing his or her music, you know? How can I talk about a writer who’s supposed to be so prolific, so amazing, so sensitive — why should you believe me? You need to see some glimpse of it. And the reason sometimes I wanted to keep this ambiguous seamlessness in the way I weave [the stories in] was also because I felt, in his own work, the lines between fact and fiction are blurred. And I like that quality . . . So I wanted to also keep that line blurred.

MC: Why was Nawazuddin Siddiqui the right actor to play Manto?

ND: Well, one, I’ve known him for 10 years. He was in Firaaq, my first film [as a director], so he was accessible. But the main thing was, I wanted an actor who can melt into a character, and especially to show contradictions in a believable manner. The actor should not be more dominant than the character. And sometimes you do see the actor in certain characters, but Nawaz has the quality that he kind of becomes the character. And I wanted someone who can be arrogant and vulnerable at the same time; there are few actors who can do that in a believable manner.

And also, Nawaz’s eyes are very powerful. He’s lived life, he’s struggled a lot. That’s something you can’t just [convey] with acting. Manto himself had struggled so much; if you see his older photographs, he looks much older than 42. There was something about [Siddiqui’s] eyes that I felt would convey much more than the words and the performance, so to say.

MC: There’s certainly something about those people who deal in taboo that seems to lead to a short, tragic life.

ND: There have been many, I think, in history. There are musicians, there are writers, there are many people who have gone through that kind of misery. They are so deeply sensitive and they are misfits, they are misunderstood, and their struggles . . . there are parallels. There are many Manto-esque people, and the idea of doing this film was not just to introduce the world — and even Indians or Pakistanis or South Asians — to Manto, but also to invoke that Manto-ness that exists within also of us. It’s a homage to all other Mantos that live even now, and we don’t shine our light on them because they drink or they smoke or they’re blunt or they’re rude. We forget the inner truth in the core and we become moralistic, righteous people and judge them, and history has judged them and not given them their due. So this film also wants to celebrate other Mantos.

Main Image Photo Credit: www.tiff.net

Matthew Currie

Author

A long-standing entertainment journalist, Currie is a graduate of the Professional Writing program at Toronto’s York University. He has spent the past number of years working as a freelancer for ANOKHI and for diverse publications such as Sharp, TV Week, CAA’s Westworld and BC Business. Currie ...