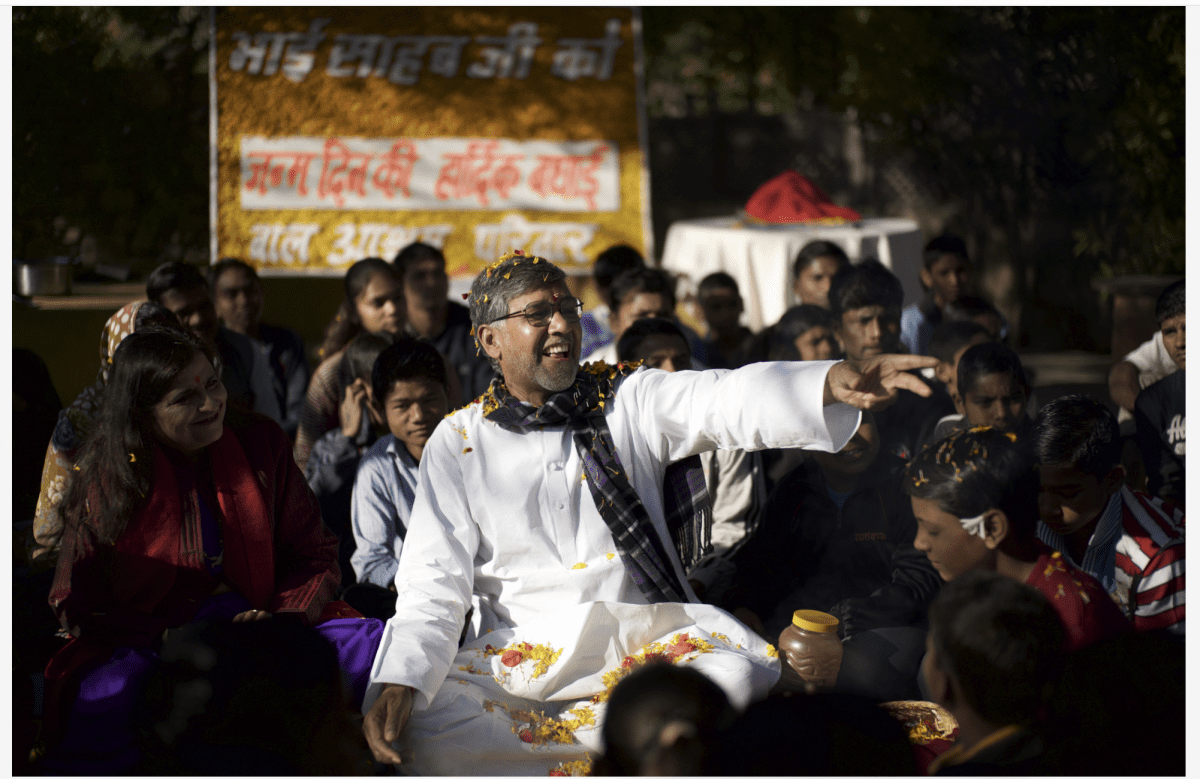

One-On-One Chat With Nobel Peace Prize Recipient Kailash Satyarthi About His Fight Against Child Slavery And The Latest Doc “The Price Of Free”

Entertainment Jan 04, 2019

The ANOKHI POWER List 2019 member and Nobel Peace Prize recipient Kailash Satyarthi chats with us about his new documentary The Price of Free, which takes viewers inside his decades-long fight to liberate child labourers.

Back in 2014, the famous, fearless Malala Yousafzai was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for her work on behalf of girls’ education. Even before that historic occasion, Malala was an icon, which is why it’s easy to forget that she actually shared that year’s Prize with another tireless advocate for children, Kailash Satyarthi, the Indian engineer turned crusader against child labour.

Satyarthi’s efforts to end child exploitation across the globe recently got a much-needed boost, when Sundance-winning documentary The Price of Free debuted on YouTube. Directed by first-time filmmaker Derek Doneen, it follows Satyarthi and his team as they embark on perilous raids to find missing children who’ve been forced into factory work, with the goal of not only freeing them, but rehabilitating, supporting, educating and setting them on the path to a real childhood.

ANOKHI got the chance to speak with Satyarthi about his film, his Nobel Peace Prize and his ongoing mission.

Matt Currie: What does it mean to you to have this film made documenting your efforts?

Kailash Satyarthi: It has a very strong message that those who think that child slavery has been abolished, it is not true. Clearly, it is still existing in its cruelest form . . . It is my hope that this film will motivate the youth and create a worldwide movement which I have launched called 100 Million for 100 Million, and it will help in inciting the masses. One hundred million young people are the victims of violence, slavery, trafficking, etc. but on the other hand, hundreds of millions of youth are ready to do something good for their society. They are full of energy and enthusiasm, but they also have an element of compassion.

So 100 million young people should be the spokespeople and change-makers for 100 million left out children in the world. And we are using the documentary and the power of media, the power of YouTube to build this campaign.

MC: What was your reaction the first time you saw the completed film, which was actually originally titled Kailash?

KS: It’s a big film, no doubt about it. It’s a documentary not exactly about my life, but largely about my life, but more importantly about the work and the children who have so much resilience, who have so much courage and so much credit for changing their own lives, which is depicted in the film very beautifully.

MC: What is the biggest challenge to your goal, your movement?

KS: The biggest challenge is definitely the mindset of the society which does not consider other children as our children. Many people exploit children as child labourers or child prostitutes or sexually abuse them, and it goes on in different forms. Secondly, we still don’t have the global political will and priority of the government to ensure safety, health and education for children in policies and programs run by the state.

MC: Can you take me back to the moment when you decided to adopt this issue as your life’s work?

KS: It grew gradually. The start was when I went to school for the first time, at the age of five-and-a-half years. I encountered a boy of my age sitting outside on the street, and that disturbed me mentally. I could not believe why are some children working on the street and not going to school. When I asked my teacher, and my family and friends, everybody tried to convince me that, “They’re poor children, there’s nothing [to be done],” but I could not be convinced. And one day when I asked the boy and his father, the father answered and he said, “You guys all want to go to school, but we want to work.” And I could not believe why some children would want to work, as opposed to freedom, education and future. In childhood, that is non-negotiable for me. That gave me a new perspective on life. I started questioning things around me, and I could not believe the people who were saying, “This is the social norm.”

MC: What did it mean to you to win the Nobel Prize?

KS: It was a big surprise for me. I never suspected that I would be the first Indian who lived and worked and studied in India to be the Nobel Peace Laureate. So it was a big surprise when the announcement was made. My spontaneous reaction was . . . the voices of voiceless children, the faces of the faceless children of the world was being recognized and being empowered by the podium of the Nobel Peace Prize.

MC: Was it meaningful to you to share that year’s prize with someone like Malala Yousafzai? Her work seems to overlap with your own.

KS: Yes, of course, because she has been raising the issue of girls in schools in her community, and she was shot at for that . . . I felt that I’m going to receive this prize with my daughter, even today I call her “daughter.”

MC: What were your initial conversations like with the director?

KS: It’s a big film, no doubt about it. It’s a documentary not exactly about my life, but largely about my life, but more importantly about the work and the children who have so much resilience, who have so much courage and so much credit for changing their own lives, which is depicted in the film very beautifully and strongly.

MC: Obviously, a big part of the blames lies with consumers across the world, who purchase products that were manufactured by child labourers. What would you say to them?

KS: Well, consumers have the biggest power in an economy. And if the consumer power is converted into a compassionate behaviour, a responsible behaviour, then we can achieve many things. The consumer power can be the guiding force. And it starts with educating consumers [about the issues]. I’m not against any industry . . . I want to engage the companies in dialogue to ensure that no child labour is involved in their supply chain. But that is not an easy thing. So I also want consumers to ask before they buy; that will help in putting pressure on the shop people and eventually on the [manufacturers].

Main Photo Credit: SoulPancake

Matthew Currie

Author

A long-standing entertainment journalist, Currie is a graduate of the Professional Writing program at Toronto’s York University. He has spent the past number of years working as a freelancer for ANOKHI and for diverse publications such as Sharp, TV Week, CAA’s Westworld and BC Business. Currie ...