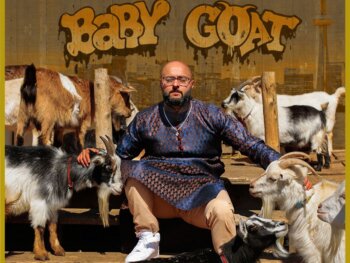

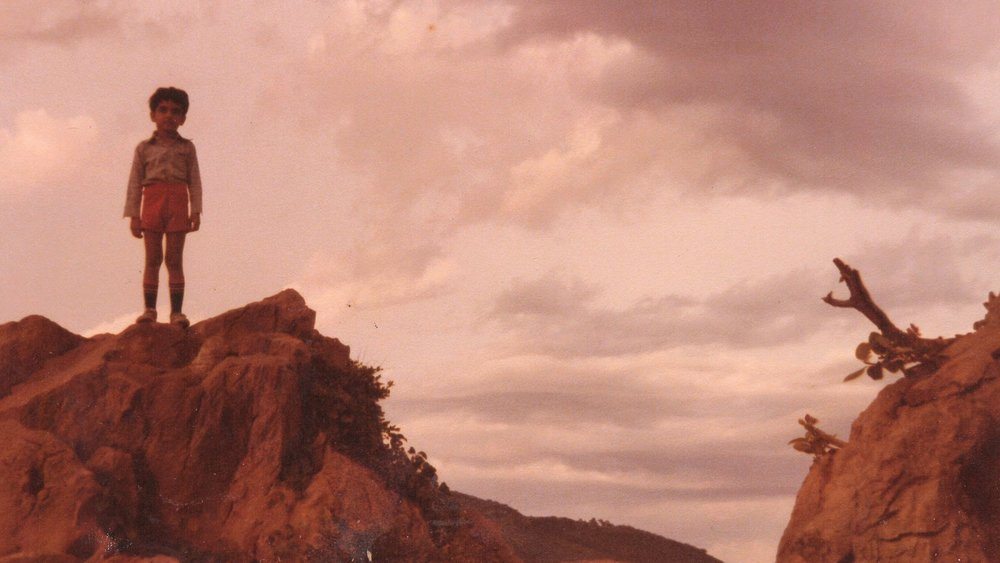

Arshad Khan Fearlessly Confronts Father-Son Issues In His Debut LGBTQ Documentary “ABU”

Entertainment Apr 06, 2018

A gay man uses his debut LGBTQ documentary ABU to come to terms with his father’s life and death. Here is our one-on-one with director Arshad Khan.

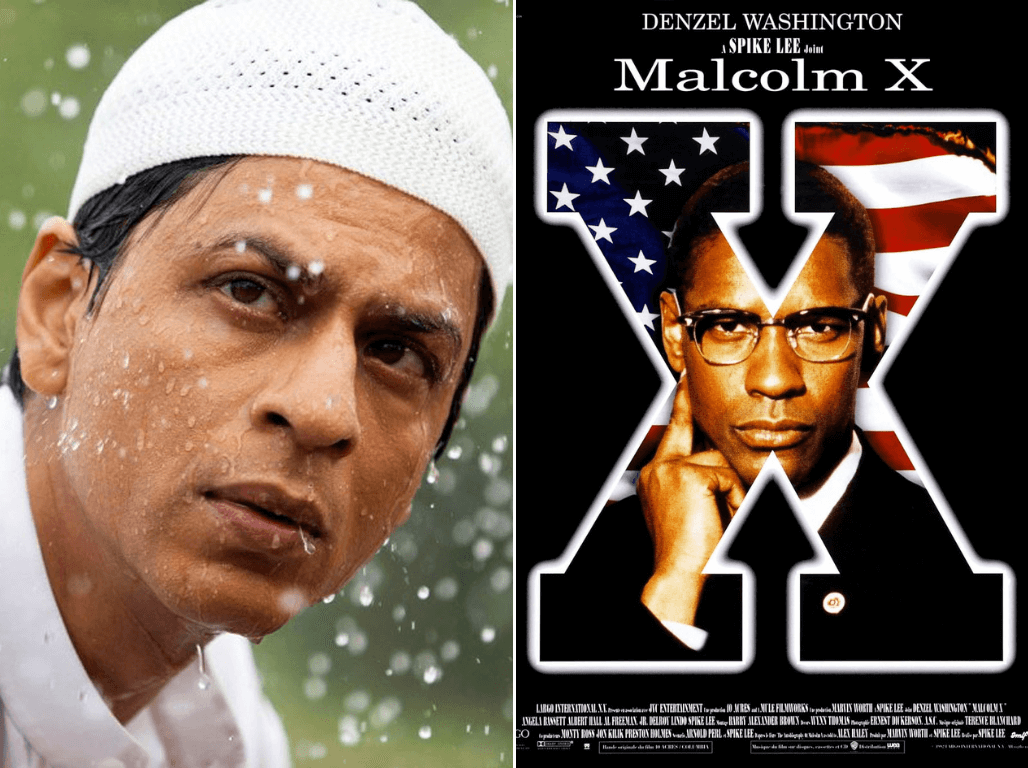

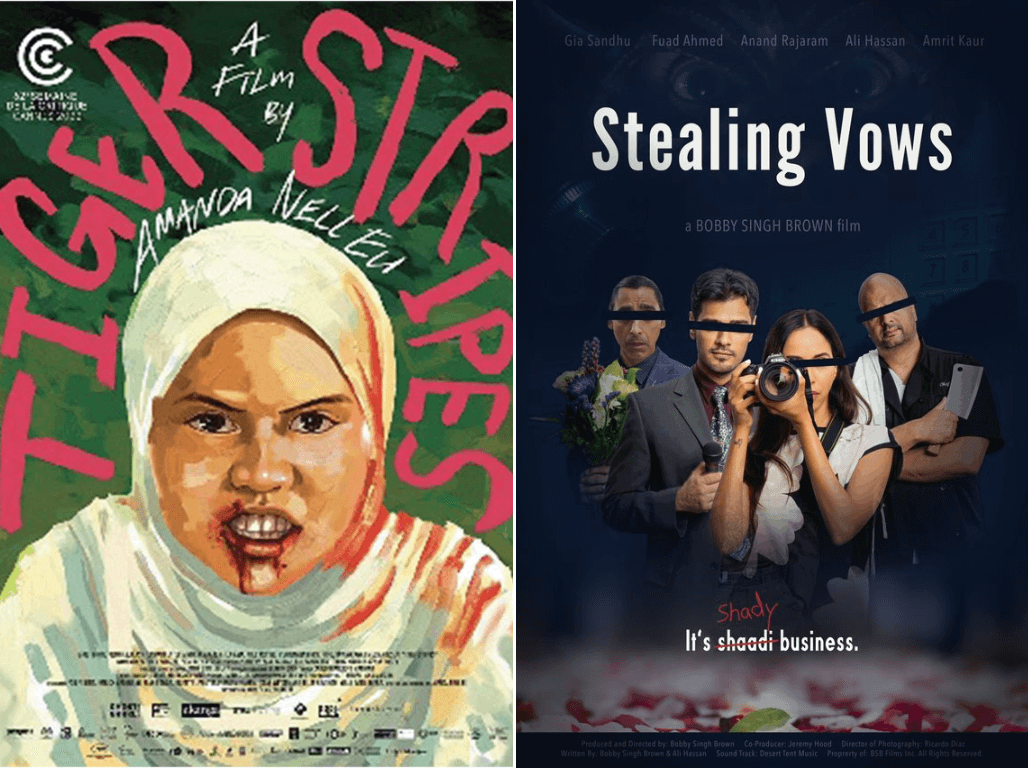

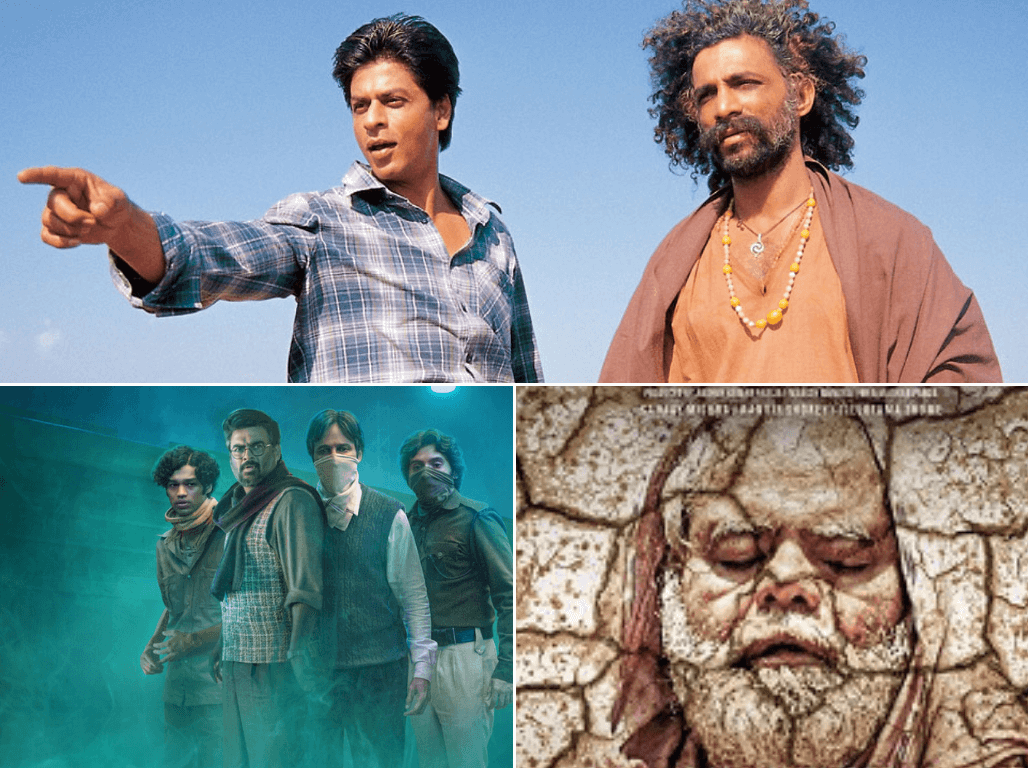

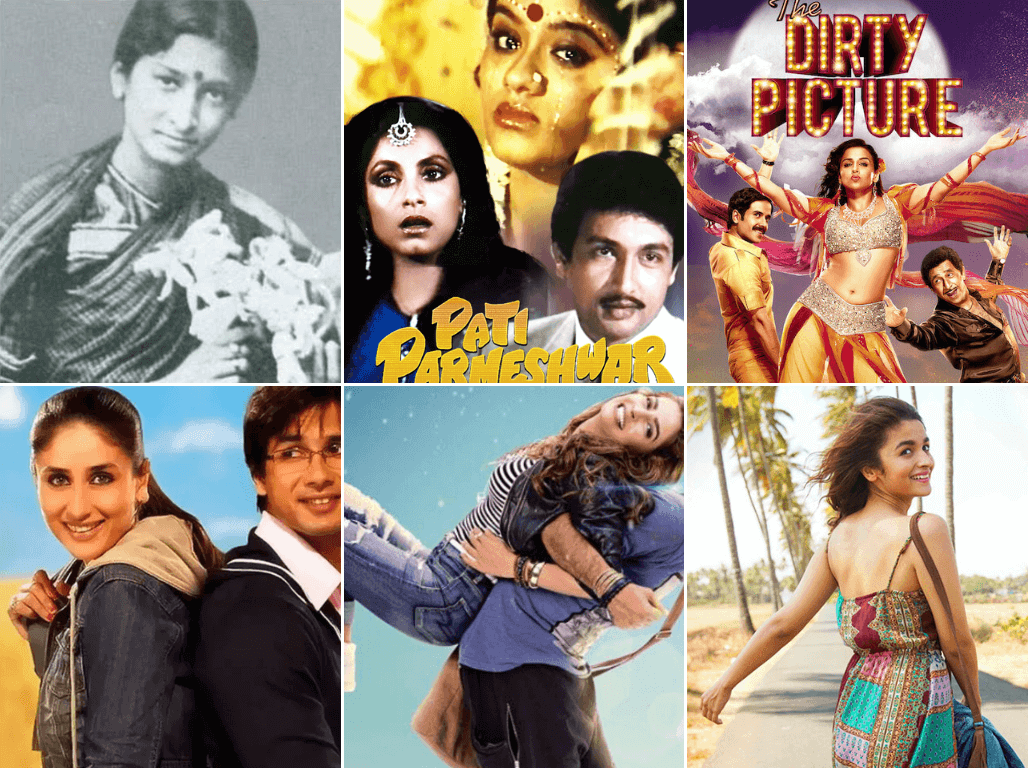

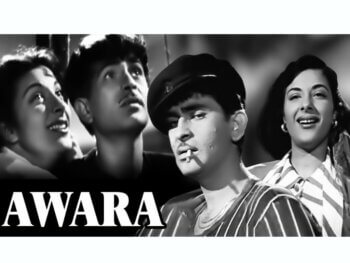

Pakistani-Canadian director Arshad Khan has been turning heads on the festival circuit lately with his debut documentary feature. It’s called ABU and in it, Khan, a gay man, delves unflinchingly into his own complicated relationship with his late father, a devout Muslim. It’s a film that’s at once deeply personal and universally relatable, poignant but infectiously playful. Khan employs a combination of old home movies, new interviews with family, clips from classic Bollywood pictures and genuinely striking animated sequences to tell the dual stories of a father and son pulled down different paths but still irrevocably bound to one another, while also touching on the ideologies, institutions and countries that shaped them both.

ABU opens in select cities on Friday, April 13, and ahead of the film’s release, we got the chance to chat with Khan about the painful, cathartic, enlightening and inspiring experience of bringing his father’s story to the masses.

Matthew Currie: This is a film that touches on a lot of larger issues — religion, colonialism, conservatism vs. liberalism, the immigrant experience, grappling with one’s sexuality. When you first started making this film, were those things on your agenda to tackle, or was this just a profile of your dad?

Arshad Khan: I set out to make a documentary examining my father. Because I had a very difficult relationship with him, and when he died, my whole world kind of was in turmoil and I couldn’t understand why. I wanted to examine that and how he affected so much of my life. I really didn’t want to be in it, myself at all. But I realized that I needed to put myself in the film to give it more weight and balance. And then I realized now I need to talk about myself more than just superficially.

MC: Did making this film change the way you see yourself?

AK: You have two lives. One is when your parents are alive and the other is after your parents pass away. Because it really changes you, fundamentally. You think they’re going to live forever and then they don’t. And after they die, it’s very difficult. You realize that a very important protection is gone. My friend said something very interesting to me: “If your parent passes away and you had a good relationship with them, you go through mourning and it’s hard, but when your parent passes away and you had a difficult relationship with them, then you go through what it called complicated grieving.” I’m someone who went through complicated grieving; and in my examination of that relationship and [my father’s] life, I realized a lot of things and I became a lot more sympathetic to his struggle than I was willing to be when he was alive.

MC: If you hadn’t made this film, do you think you could have come to terms with this complicated grief?

AK: Yes, I could have. But to be creative with it was better. Something positive came out of that. And to be able to share it is very special.

AK: Actually, it was very shocking, to tell you the truth. Because, my family and friends, they know me, they already like the film . . . I thought, beyond that, people will be like, “It’s OK. It’s interesting.” But, my goodness, after every screening, people literally are shaking and crying and they hug me, and they’re like, “You’ve shown the story of so many.” That’s a reaction I never expected. And this is from non-South Asians; these are people who are not South Asian, not Muslim, not even gay, sometimes. And they’re like, “You know what? We completely related to that. It reminds me of my dad.”

MC: What made you want to incorporate the animated sequences and the Bollywood clips?

AK: I wanted to make a film that will open people’s minds and eyes and hearts, but also entertain them. That’s why people love the film. They always tell me that the film is very hard to watch but at the end of the day, it’s a hopeful film. I wanted to make a fun film and so I used all the tricks that I had from fiction to tell this documentary tale. I used animation, I used Bollywood clips, I used Hollywood clips, I used anecdotes . . . and I found animation to be a very effective way of telling the essential components of the story which I couldn’t see any other way of telling.

MC: You collaborated with Deepa Mehta on this. What was that like?

AK: She has been a huge supporter of my work, and she’s a wonderful collaborator. Narration is the backbone of my film, so she said, “Take your director’s hat off, put your actor’s hat on and come to Toronto” and she directed my narration. And it made a big difference.

MC: You’re quite vocal about your political convictions, and this film definitely touches on post-9/11 life in North America and the rest of the world. Has that outspokenness always been in you, or was there a time you were hesitant to speak up?

AK: I remember a producer telling me once, “You know, Ashad, you need to tone this down, or in this profession, you won’t get very far.” He was being very sincere to me and being very nice to me, because he liked me . . . But I didn’t want to become a filmmaker to become famous; I became a filmmaker because I was angry about the lack of representation of my people and my voice, with the War on Terror, with the perversion of our identity, the association of the word “terror” with Muslim people and Pakistani and South Asian people, the criminalization of our skin colour . . . It was after 9/11 that I really realized there was something wrong with the media. Because our voices are just suppressed or buried or invisible. We’re not there. And I said, “That’s not good enough.”

MC: This is such a deeply personal film for you. In putting it together, what did you learn about yourself and what did you learn about yourself as a filmmaker?

AK: I learned most importantly that if you’re sincere, others feel it. And sincere filmmaking is what people want. No matter what format you’re using — documentary, fiction, doesn’t matter. I didn’t realize that before. The more authentic your voice is, the more universal your work is.

Main Image Photo Credit: Gray Matters Productions

Matthew Currie

Author

A long-standing entertainment journalist, Currie is a graduate of the Professional Writing program at Toronto’s York University. He has spent the past number of years working as a freelancer for ANOKHI and for diverse publications such as Sharp, TV Week, CAA’s Westworld and BC Business. Currie ...