We continue our holiday series Our #ICYMI Stories Of 2020, by asking why our Desi community is so hesitant to accept South Asian lesbians.

With Pride Month coming to a close, we conclude our LGBTQIA+ – focused stories with our final and most poignant piece.

We read a lot about the gay movement within the Indian diaspora and mainstream South Asian communities. However, when it comes to the South Asian lesbian community it seems that our Desi community isn’t willing to accept those truths. We take an historical look at how the South Asian lesbian community grew into a movement and how it’s regarded today while asking ourselves: why does our community find it harder to accept Desi lesbians?

Up until 2009, the Indian Penal Code, according to Section 377, maintained that homosexuality was a criminal act. However, the Supreme Court of New Delhi came under fire for this decision, notes The Reader, as “…many religious leaders, including Islamists, [felt the decriminalization of homosexuality was a] “dangerous move that [would] contribute to importing Western culture into India and corrupting young Indians.”” As such, much to the dismay of the LGBTQIA+ (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Pansexual, Transgender, Genderqueer, Queer, Intersexed, Agender, Asexual, and Ally) community, Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code was reinstated in December 2013. As such, individuals who were discovered engaging in same-sex could be subjected to spending the rest of their days in jail.

However, nearly five years later, in September 2018, Section 377 was once again repealed “…in a landmark decision, Navtej Singh Johar v. Union of India, decriminalizing consensual sexual intercourse between consenting adults of the same sex,” reports Fair Observer.

While this was a monumental victory for the LGBTQIA+ community in India, there is still much work to be done, particularly for the plight of lesbians in the South Asian community.

Let Us Explore the History of Lesbianism in South Asia:

In the past, there have been many examples of homosexuality throughout South Asia. For example, according to Surina A. Khan’s article, “Sex and Oppression in South Asia,” same-sex couples in the throes of passion were inscribed “in the temples of Khajuraho and Konarek in India,” while the infamous Kama Sutra alludes “…to homosexuality.” Khan also notes that both “Babar, the founder of the Mughal dynasty in India [and] Abu Nawas, a famous Islamic poet,” were rumoured to have been homosexual. These examples validate two points: 1) lesbians and gays have existed throughout history in South Asia, and 2) belonging to the LGBTQIA+ community is not simply a North American concept.

According to Khan for South Asians conversations surrounding intercourse are scarce, never mind talking about matters relating to the LGBTQIA+ community. While this has been problematic for the LGBTQIA+ group in South Asia, the lesbian community has been forced to operate covertly. As such, the group is “…not only invisible but fragmented, and [they are] under-represented in media, literature, film, and politics,” explains Khan.

This lack of visibility has made it difficult for lesbians, notes Khan, to embrace “their sexual identity” within the South Asian community, which often results in them “assimilating into Western culture.” Ultimately, this lack of acceptance by the South Asian community serves as a hindrance for “South Asian lesbians [in] building a strong and vibrant and visible…community,” explains Khan.

Instead, South Asian lesbians sought underground or unofficial ways to network within their own community. Advocates for lesbians in India started their work in the ’80s by creating global networks of support, as opposed to domestic groups. One of the earliest documented gatherings, notes Khan, was “in 1985 [when] Indian delegates attended a workshop for lesbians at the Nairobi Women’s Conference.” Then, in 1990, notes Indian Express “seven Indian women activists from Bombay and Delhi attended a conference of the Asian Lesbian Network in Bangkok.”

During the same year, in a ground-breaking move, the Bombay Dost printed a declaration by written by a group of lesbians called “Sakhi” (refers to a “female companion, friend, lover”), according to Giti Thadani’s book, Sakhiyani: Lesbian Desire in Ancient and Modern India (2016). This announcement, a first for the lesbian community in South Asia, outlined “the necessity of networking, the creation of lesbian visibility, the challenging of lesbophobia and the internalization of heterosexual roles even within lesbian relationships, and the demarcation of its differences with the male gay movement,” explains Thadani.

According to Thadani, the group identified as Sakhi, as when this term was linked to “…the word lesbian” it worked to invalidate the “…desexualization of [female] friendships,” while also providing a word for lesbians to identify with and, ultimately, exist. Using the word sakhi created an informal and covert way for lesbians to express their sexual orientation.

Enter Thadani, in 1991, who established one of the first support groups of South Asian lesbians, aptly named Sakhi, whereby women could write to one another. According to the Hindustani Times, Sakhi often featured ads “the Bombay Dost, and women responded to those advertisements, writing in to Sakhi and seeking others like them to correspond with.”

How Does South Asian Culture Impact Lesbians?

Despite homosexual acts being legalized, it is difficult for women to ‘come out’ due to the deeply entrenched patriarchal nature of South Asian society. According to The Reader, “societal values, the caste system, arranged marriages, the high probability of being disinherited for coming out — everything runs counter to gay liberation.”

Often, women face various forms of oppression and violence within their household when their taboo sexual orientation is discovered or revealed. According to Sutanuka Bhattacharya’s article, “A Love That Dare Not Speak Its Name: Exploring the Marginalized Status of Lesbians, Bisexual Women, and Trans-men in India,” families have been known to silence or ignore the admissions of female offspring who reveal “their non-normative sexual preference and/or gender identity, fearing social stigma and shame” from the larger community.

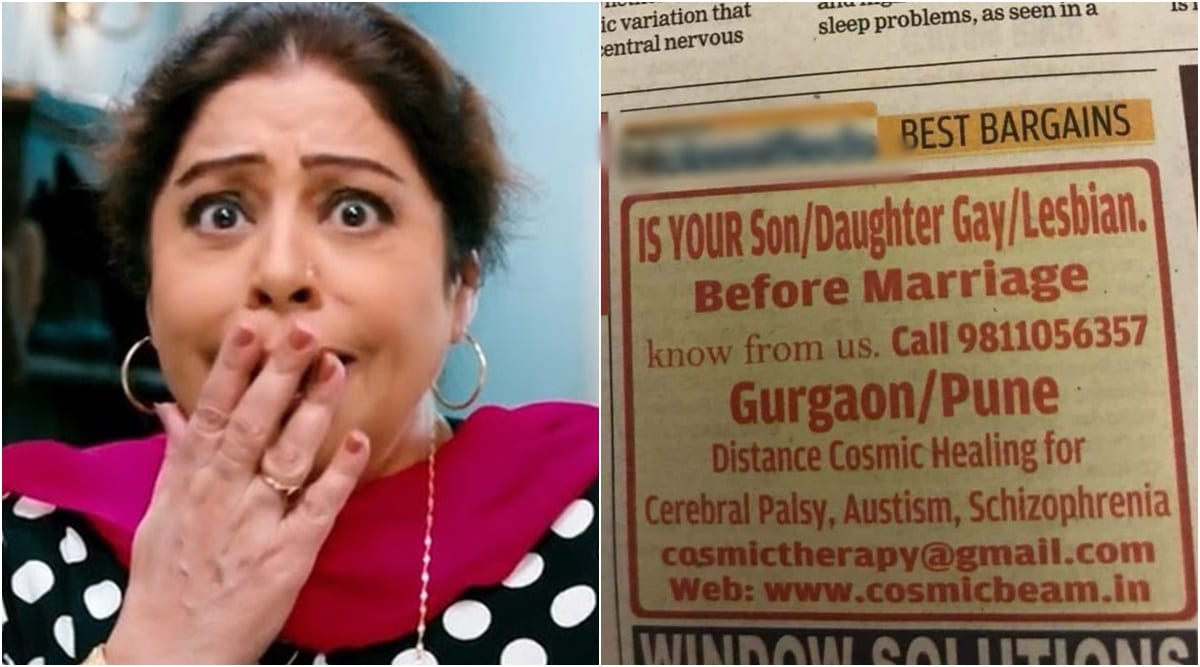

At the other end of the spectrum, families can also be brutal in their treatment of young women who ‘come out’ in their efforts to ‘save’ or ‘heal’ them. For instance, Bhattacharya notes that common dehumanizing and dangerous practices to ‘cure’ homosexuality among women within the familial household include the following: “mentally torturing LBT persons by “othering” them within their families and social circles; not recognizing their gender and/or sexual orientation; blackmailing them in the name of family honor and well being; separating them from their same-sex partners; taking them to doctors; forcing them into heterosexual marriage against their will; keeping them under house arrest for several months; restricting their mobility and access to resources such as food, education, communication etc.; beating them up; or forcing them to undergo corrective rape by their own siblings.”

Outside of the family, despite Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code being repealed, there are other legal challenges that frame the experience of same-sex couples. For instance, same-sex couples cannot be legally married in India. Evidently, in India, both “the Hindu and Christian marriage acts refer to a bride and a bridegroom,” which infers that same-sex couples do not meet these criteria. This lack of legality surrounding same-sex marriage ceremonies in India has a number of repercussions for couples, including not being able to “…jointly adopt a child, [claim] the right to maintenance, name their partners as their legal heirs,” and as same-sex spouses are not legally related, “…they are denied hospital visitation rights” according to Fair Observer.

What Successes Have The South Asian Lesbian Community Experienced?

Since their humble beginnings, the representation of the South Asian lesbian community in the mainstream media has grown with a number of Indian celebrities, including Vasu Primlani and Shonali Bose, identifying as either a lesbian or bi-sexual. Coming out in the public eye is significant as it can provide the courage for others to come out. Similarly, in 2015, Anouk an Indian clothing company released a revolutionary advertisement that starred a lesbian couple.

In India, there has been some progress for the LGBTQIA+ community, insofar that Pride parades have been able to gather in large metropolitans (although they can be subject to police brutality). The Reader highlights that there are also “‘pink nights’ in nightclubs, a Queer Ink gay bookstore in Mumbai, and Bollywood stars who sometimes perform gay characters.” Importantly, in India, governing bodies have legalized the ability of groups who work to uphold “…gay rights, such as the Naz Foundation,” outlines The Reader.

The movie Ek Ladki Ko Dekha Toh Aisa Laga (2019) starring popular Bollywood actress, Sonam Kapoor Ahuja told the story of a lesbian romance for the first time on the big screen. “Art is a reflection of society. Once in a while, you create something that can affect change in some way,” She told us (while doing press for the movie) what it meant for her to be a part of such a ground-breaking project. “And I endeavour to be part of art like that. Films like Pad Man or Veere Di Wedding or even Ek Ladki Ko Dekha are those sorts of films where they are aspirational or are symbolic or have something to say. I think it’s important to be part of films like that . . .and [also] to entertain the audience, because if it’s not entertaining, they’re not going to come in and watch what you have to say.” That said, despite the film’s significance to the LGBTQIA+ community, unsurprisingly, the movie did not reap much at the box office, earning approximately $2,181,731 (USD).

Meanwhile in the hit Amazon series, Four More Shots Please! one of the leads is Umang (played by Gurbani Judge, also known as Bani J) who is a bi-sexual. It is interesting to note Judge’s character is a bi-sexual, rather than a lesbian, as South Asian culture does not seem to be ready to accept this type of identity as it goes against its core patriarchal beliefs.

Evidently, a woman can dabble while she goes through a ‘phase’, but she must return to her hetero-normative role to be a part of the South Asian community.

What’s Next?

While legalizing same-sex marriage would be a major win in India toward equality for same-sex couples, protecting women who identify with the LGBTQIA+ community from the limiting patriarchal expectations that supports South Asian culture is equally important. To aid in these efforts, there needs to be a clear ban on conversion therapy and work needs to be done at a communal level to challenge and eradicate the discriminatory beliefs South Asians have about homosexuality and marriage. Laws need to be enacted to protect Indians against discriminatory measures taken against them as a result of their sexual orientation. As well, members of the LGBTQIA+ community are seeking protections within the workplace to ensure that they can be gainfully employed without fear of discrimination.

That said, if you’re looking for support or ways to be an ally, there are a number of organizations that are doing important work to help the lesbian community in India, such as Nazaria and Sappho for Equality (or click here for the full list).

Of course, bringing down a patriarchal and oppressive system that is at the core of South Asian culture will be no easy feat for the lesbian community in particular, but I believe it will be possible because (as basic as it sounds) love should and will persevere.

Main Image Photo Credit: www.wikipedia.org

Devika Goberdhan | Features Editor - Fashion

Author

Devika (@goberdhan.devika) is an MA graduate who specialized in Political Science at York University. Her passion and research throughout her graduate studies pushed her to learn about and unpack hot button issues. Thus, since starting at ANOKHI in 2016, she has written extensively about many challe...