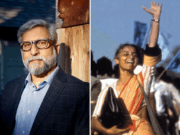

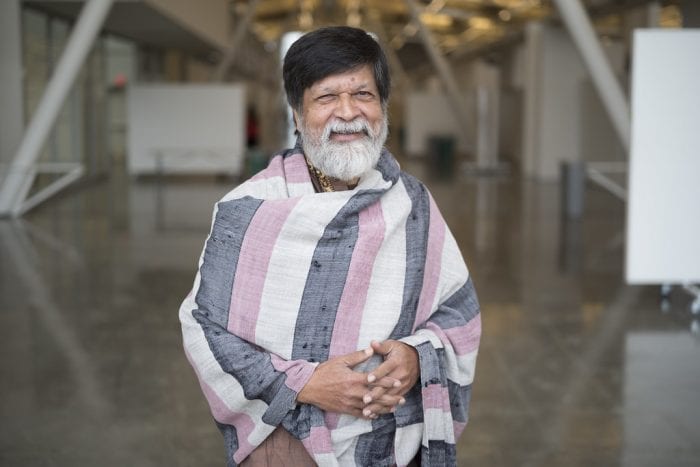

A Chat With Human Rights Activist & Bangladeshi Journalist Shahidul Alam On His Battle For Freedom To Dissent

Lifestyle Nov 01, 2019

Human rights activist and journalist Shahidul Alam sat down with us to chat about the current crisis of dissent in Bangladesh. His detention and torture, being strategic when calling out truth to power and what “elections” really mean to him.

Shahidul Alam, 63, has been through hell and back. The Bangladeshi journalist and human rights activist first made headlines last year when he was detained after giving an interview to Al Jazeera and posting a series of videos on Facebook that candidly criticized the local government’s violent response to student-led-protests. His detainment and torture prompted an immediate outcry by local and international groups alike and he was granted bail on November 15, 2018.

He currently faces charges under Section 57 of Bangladesh’s Information Communication Technology Act. If convicted, it could mean another 14 years in prison. But Alam is undeterred.

We caught up with him at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto where he delivered a lecture on ‘Creating Spaces for Dissent’ — an account of a torrid love affair with photography, creating stories that matter and paving the way to educate and inform local youth.

Devika Desai: It’s ironic that your lecture is titled ‘Creating Spaces For Dissent’ given that the Bangladeshi government has been proven to do the exact opposite. Is the irony intentional?

Shahidul Alam: (Chuckles). What I will be talking about in my lecture is the fact that you work in complex situations, and at the end of the day, it’s a question of being strategic. While one is required to challenge authority, one also needs to be pragmatic and find ways through which you can continue to work. One of the ways through which I do it is to make repression expensive. You make it difficult for people to be oppressive, at the same time empowering those who are oppressed.

So what I’ve chosen to do is work on three areas of intervention: media, education and culture. With these three prongs of public engagement, I try to exercise pressure upon the political space so politicians cannot get away with the indiscretions that they normally shouldn’t be getting away with.

DD: Well, Sheikha Hasina’s party was re-elected last December …

SH: Well that depends on how you define election, that would imply people had a vote.

DD: Right. Many media reports have indicated that she won through a campaign of intimidation and violence. How, do you think, she might have fared if the election was carried out democratically?

SH: We have no way of knowing but we are told that intelligence services have done a fairly extensive survey of the situation underground and submitted that had there been a genuine election, she would have been wiped out. I suspect that might be why they chose not to go into an election at all.

To be fair, I don’t think the opposition is any better. I am not a partisan person. I think, given a situation of absolute power where your authority is unchallenged, anyone would act (similarly) in that situation — the angels would be corrupt. What needs to change is the process by which people are governed and ensure that there is accountability and transparency. If Hasina rightfully comes back into power because the people want her to, so be it, but she must know it is the people who decide.

DD: What are your thoughts on the current state of international politics?

SH: I don’t really believe there is such a thing called morality in international politics. It is petty interest, usually self-interest and one needs to accept that that’s the case. Therefore what you need to ensure is that politicians are held to account. and when that’s the case, I think that it will be a different situation. We have Modi in India. We have Trump. Hasina in Bangladesh. Saudi Arabia. Myanmar. They do not hold monopoly on repression but i think our job is to ensure that the public are in power, that the will of the people come in and given that situation I think, we will choose the right people.

DD: Despite being criticized internationally, especially by United Nation human rights experts Bangladesh took a seat on the United Nations Human Rights Council last October. What does this say about the state of global human rights?

SH: Firstly, i don’t think the United Nations is a United Nation. The fact that there are things like vetoes, that questions the very principles of democracy. Further than that you have an entity like the Security Council, made up of the largest warmongers in the world — it’s like handing your children to a pedophile for protection. The UN has failed, the Non-Alignment Movement (NAM) had potential but that too didn’t quite succeed. At the end of the day it’s important for the majority of human kinds to recognize that, one, they’re the guardians of the human planet and two, as guardians of this planet we need to play a more responsible role. What has happened is that we have over a period of time, given that space little by little until our backs are against the wall and that space has been occupied by others. We need to reclaim our commons.

To a very large extent, I think private media has t become the spokesperson of the government. The media to a large extent has sold out, they no longer perform for the state. I think they have some hard questions to answer.

DD: How can the public subvert social barriers placed by the authorities so as to highlight the need for social justice?

SH: Certainly working together, finding ways to collaborate and i think at the end of the day, we need to take over the streets. They have weapons, they have money but we have integrity and belief we need to claim our land. If the public of Bangladesh took over the streets, no autocrat would ever survive. The reason they get away with it is because people are scared and there is no leadership and because there are not those people who are prepared to take the first step.

DD: Well, some people might use what happened to you as an example to stay silent.

SH: And that is the purpose of their exercise. But if you look at it the other way around, in a country like mine, they put away Professor Yunus, they sent the Chief Justice into exile, they jailed the leader of opposition. But me, an ordinary citizen, the public outcry was something remarkable. People nationally took far greater risks than the people on the outside and they resisted and created a situation that was untenable, even for a government as autocratic as we have. I think it is a victory for the people.

DD: What were your first thoughts when you saw the men at your door? Did you expect it?

SH: I live and work as a journalist in Bangladesh so it’s an occupational hazard. You hope it won’t happen but you know it very might. Initially I didn’t know because it was a woman at the door who called me Uncle Shahidul. I opened the door and these people came in and I could read the situation. My intent at the time was to delay my arrest and make as much noise as I possibly could to ensure that I didn’t go away quietly. My concern was if I could be taken away quietly and enough time passed, it might be too late. I resisted, I screamed, I made it difficult and while they were able to take me away, people knew what had happened. Of course, I didn’t have access to information when I was being tortured but afterwards when I was being driven to court and saw my students on the street, I knew they knew i was there and I knew they would not let it pass.

DD: In another interview you said the judge had mentioned you were lucky to have not disappeared. Was that a concern of yours?

SH: Certainly when I was picked up, I didn’t know if I would live. But I knew what I had to do and had the situation been reversed my family would have done exactly the same as I did. When I did talk to my lawyer and they asked me, whether I took a deal that offered me release provided I stay silent, and I said of course not — I could see the relief in their faces and thanked me for saying no, knowing what I had been through physically and mentally. There are many who disappear with no one to speak out for them so, as a person in a privileged position, the least I can do is what I’m required to do.

DD: And you’ve continued to do so, despite the upcoming trial.

SH: I’m a citizen of a sovereign state and my constitution gives me rights. I will exercise those rights and if others have problems, they can deal with it.

DD: What kind of impact do you think your actions have had?

SH: On the flight, a young woman gave me a letter, in which was an outpouring of her feelings on how I had stood up for her and this country. When I arrived at the hotel, there were people around me. I have people hugging me with tears. When I was coming out of my office, a young woman came up to me with her baby and asked me to bless her child and said, “I want him to grow up to be as brave as you.” I was choking.

I see middle class workers telling their children to keep their heads down but the garment workers of my country, the farmers who have created the wealth that the privileged live on, they have not sold out. They still believe and are prepared to make those sacrifices. I think it is time that we recognize those people on whose shoulders we have gotten the wealth that we have.

Alam is also the founder of Drik Photography, an award-winning picture agency set up to support local photographers and Pathshala, a world-renowned media institute for photography.

Main Image Photo Credit: https://news.artnet.com

Devika Desai

Author

Devika (@DevikaDesai1) has a Masters in Journalism from Ryerson University. She's currently a web producer for the National Post. She has also interned at MidDay, a Mumbai-based tabloid. In her free time, she loves to read, work out once every blue moon and ask strangers if she can pet their dogs.