South Asian Heritage Month 2021: #Reclaimingmyname — We Need To Stop Mispronouncing Our Name For The Benefit Of Others

Lifestyle May 31, 2021

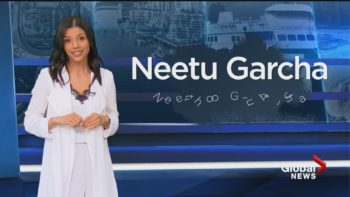

Actress Thandie Newton made headlines when she declared that she was going back to her name as originally intended — Thandiwe. Then journalist Neetu Garcha from Global BC released a segment about how she has been deliberately mispronouncing her name for the convenience of others. Inspired by these stories and to close out South Asian Heritage Month, I asked a group of South Asian women from different generations, about mispronouncing their own names, the importance of authenticity and the reasons why we need to stop.

There’s this four letter word that has caused so much confusion throughout my life.

Hina.

My name.

It’s pronounced with a short ‘i’. Not an exaggerated ‘e’. It’s just a short ‘i’.

Starbucks baristas aside (because I think that’s a whole other conversation), I find it interesting that people would just decide on their own what the correct pronunciation of my name would be. More often than not, it would just get to a point where the person has been saying my name their way for so long; I just don’t bother to correct them, fully understanding that window of opportunity closed a long time ago. Now I have to remember when they are saying “Heena” or “Hanna” that they are talking to me.

But it seems that things are changing.

I could look at it as a bi-product of last summer’s Black Lives Matter revolution, which pushed BIPOC voices to the forefront, along with it, a self-introspection of one’s own identity and discovering the heritage of their names along the way. Or to put it more simply, it could also be because of the growing multicultural mosaic in our society. Whatever it is, one thing’s for sure: there is a shift.

I still remember the 2017 clip of Uzo Aduba (Orange is the New Black) giving a lecture at a Global Citizen event about wanting to change her Nigerian name as a child. “I came home from school one day and my mom was cooking in the kitchen … I said ‘Mommy, can you call me Zoe?’. She stopped and gave that mother look that only mothers know and have. And I say ‘because no one can say ‘Uzoamaka’. She looked at me and said ‘If they can learn to say Tchaikovsky, Michelangelo and Dostoyevsky, then they can learn to say Uzoamaka’. I never asked her that question again.”

“What is amazing now, standing in my womanhood, in my power is I wouldn’t change my name in a second.” Aduba concluded, “I’m so proud of my name, what stemmed it and what it represents.”

In March of this year, Hollywood actress Thandie Newton (Westworld) announced that she was going to reclaim the original spelling of her Zulu name, Thandiwe (which means “beloved”), and use it moving it forward, telling British Vogue, “I’m taking back what’s mine.”

A month later, it was Neetu Garcha’s turn. In April, this Global BC reporter released “What’s in a name? Neetu Garcha on why getting it right matters” a video segment about how she deliberately mispronounced her name for the comfort of others. And it was time to stop. She was also reclaiming her name — and its correct pronunciation back. Adding her voice — and her name — to the #Reclaimingmyname hashtag on social.

I was intrigued. Mainly because I have always been interested in why South Asians specifically, would give an anglicized bent to their names. Kamran would be “Cameron”. Rohan would be “Ro”, Samira would be “Sam”. Kalki would be “Kelly”. So on and so forth.

It probably boils down to addressing the comfort of others before your own. When it comes to acceptance in mainstream society, that boat shall not be rocked. So the general attitude of ‘call me whatever you makes you feel comfortable’ reverberates across cubicles, zoom screens and classrooms of this society.

It was in university where I was seriously considering changing my legal name from Hina to Henna. It meant the same thing, so that won’t be lost. And everyone knew what Henna was thanks to healthy doses of Gwen Stefani and her flirtatious relationship with South Asian elements. But at least people will be able to pronounce my name without bearing the brunt of that awkward pause before it escapes their lips. I was very close to doing it but backed out. For fear of my parents’ wrath, understandably so.

Janani’s Journey

Janani Shanmuganathan a 34-year-old Toronto lawyer, and partner at Goddard & Shanmuganathan LLP had a relatively uneventful elementary and high school career when it came to her name. She was part of a robust South Asian community in Malvern, a closely-knit neighbourhood of Scarborough, Ontario. Thanks to that community who also populated the classrooms, she didn’t have an issue with mispronunciation because her teachers “who were mostly white” all learned the South Asian names of their students. But that changed when she entered university.

“In undergrad, I was in a program with a lot of white kids, and they were struggling to say my name so I started to go by ‘Jana’,” she recalled.

However her scholastic and legal years did make for a unique collection of memories and references. “It’s interesting. There’s so many different people in my life and you can tell when they came into my life by how they pronounce my name,” Janani explained.

I was led to Janani on Twitter. The first thing that stood out was that she had her phonetic spelling of her name right on her Twitter bio (Jenna-knee). A gesture, which actually makes perfect sense. Of course, I asked her about it. “In many ways when people mispronounce my name, it’s not on purpose. I want to help people help pronounce my name with the phonetic spelling,” she told me.

I was curious about her name’s journey. It wasn’t until she started articling in 2011 when she decided to ditch the anglicized version and go back to her original name. To her it was “a conscious choice.” She added, “I wanted to be my authentic true self and didn’t want to pretend to be someone else. And that starts with my name. My name is ‘Janani’ and that’s how I think of myself. ‘Jana’ is a version of myself that I created for other people, but that’s not who I am.”

Janani realized how her name — and consequently, her identity — can get devalued when ignored, or dissected for the convenience of others. This was especially the case for her in the courtroom. “I go to court and often times I would be the only non-white lawyer in the courtroom.” she recalled. “And when the judge would refer to the other lawyers they would always say “Mr. So and So”. When it came to me, I was always referred to as “Counsel.” There’s nothing demeaning with the word “counsel”, but I was made to feel like an outsider where everybody else had a name.”

She wrote about it for the Criminal Lawyers Association, which got the attention of the Federation of Asian Canadian Lawyers (FACL). They in turn, created a web series where each lawyer would be asked how to pronounce their name, and invited her to be part of it. She did and it went viral in the legal space.

How do you help others pronounce your name? View the video of lawyers @Gerald_Chan_law and Janani Shanmuganathan to learn the approach @_JananiS takes when she’s in court.

Learn more about our Asian Heritage Month initiative here: https://t.co/O8dlPRHDy5 #FACLAHM19 pic.twitter.com/p3yOadC4rj

— FACL Ontario (@faclOntario) May 2, 2019

Fast forward to today, and Janani also sees the same shift that I do. “I really see a change that a lot of people are reclaiming their names,” she enthused. “I think it’s so important for future generations to see that you don’t have to change your name, like I did in undergrad. I’m hopeful that the trend will continue and conversations like this don’t need to happen because everyone just goes by their real name.”

When My Group Chat Blew Up

I immediately turned to my group chat. Consisting of some pretty fabulous women, all from different generations sharing the same sense of community. I picked up my phone and started typing. Boy, did it blow up. Here’s an excerpt of the (long) thread.

Shanta, 48

“My father, as a young doctor was known as “Sid” in small town Fort Erie because no one could say Syed. They called him that for years and many of the old school people still around from that time still call him that.

For me, I still say “Shawn-ta” rather than “Shan-tha” when I have to talk on the phone people. It’s difficult to change. But I’m making a conscious effort.”

Shazia, 39

“[My husband] Milan tells people his name is ‘Mike’. Sometimes I get so mad. He tries to tell me people can’t say his name properly and I get mad and tell him, they can learn!! Say ‘if you can learn to how to say Supercalifragilisticexpialadocious, you can figure out how to say my name’.”

Farah, 43

“In addition to letting others mispronounce my own name, I’m guilty of mispronouncing other South Asian names so that it’s easier for others to recognize who I’m speaking of.

At work, I used to say “Shank-R” and “Prooothvi”. Now that I pronounce them correctly, people ask me to repeat the name as if they don’t know who I’m talking about. Even though Shankar and Pruthvi pronounce it the same way I do. Not to mention that it’s not that hard to infer whom I’m speaking of.

I think one way we can help is by not anglicizing the sounds when speaking about each other or any non-English phrase for that matter e.g. Ram-a-dan.”

Shaheen, 53

“This is a trigger topic and loved that piece Neetu did. The system is designed for conformity that doesn’t reflect anything outside of it. So we were asked to adjust to fit into Anglo names considered the norm rather than others expanding.

My name was cringe worthy on any roll call especially the first day of school in new classrooms. It’s spelled like it sounds but was Shannon, Sheera, Charlene, Shaneen … anything other than what it is. I also adapted by correcting but making it easier to Shaheen rather than Shaaheen pronunciation. I tend to switch depending on the audience creating a duality.

The movement is a necessary and speaks to an inclusive unapologetic claiming of space.”

Samihah, 21

“Growing up I let my name be mispronounced constantly, too shy to correct others. I look back on my internalized racism, asking new friends to call me by an anglicized nickname when I started university. I did this not just to fit in or to get ahead of the awkwardness of having to correct them, but also in the hopes that it would make my name easier to remember — thereby making me easier to remember.

When I started my first clinical placement of my degree in midwifery, I found out that my classmate had already told the midwives at my placement, “just call her Sam”. It occurred to me that for her this was a simple thing. For her there was no second thought about how with those words, she disregarded my heritage, a major part of my identity, and who I am. It was most convenient to shorten my name to fit the molds of whiteness & eurocentricity.

As I continue my journey to become a health care provider, I emphasize each syllable of my name when I introduce myself and don’t offer an alternative (even when asked for one). I am vocal about the fact that all of my clients, and all people in general, deserve the respect & effort it takes to learn to pronounce their names correctly, every single time.”

Afshan, 50 (Samihah’s mom)

“We are all in the same boat.

[My daughters] Samihah and Inayah were taught to say their names properly. They repeated it properly from the start … unlike me who after over a decade felt awkward to fix it. It probably helped that they lived in a more diverse demographic.

Nonetheless … I insisted the girls owned their names from the beginning.

I believe it is changing.

On the flip side … I have a very diverse demographic at work with patients and I have learned to ask people to let me know how to say their names properly because I know it matters.

What’s in a name? A lot.”

A Worthy Weight To Carry

Indeed. Our names do hold such weight. It’s a wonderful milieu of our ancestry, culture, and a snapshot in time. So why should we continue the #reclaimingmyname movement?

“Your name is your oldest possession. You’ve had it since birth. It belongs to you.” Janani adds.

She looks to celebrities and athletes — specifically hockey players, as evidence of a selective effort that does exist. “People think that it is something of value. ‘I’m going to take the effort to pronounce their name’,” she noted. “It’s a common courtesy that should be applied to everybody. It shouldn’t just be for someone special, it should be for everyone.”

Main Image Photo Credit: www.unsplash.com

Hina P. Ansari

Author

Hina P. Ansari is a graduate from The University of Western Ontario (London, Ontario). Since then she has carved a successful career in Canada's national fashion-publishing world as the Entertainment/Photo Editor at FLARE Magazine, Canada's national fashion magazine. She was the first South Asian in...