PRIDE 2021 Special: Let Me Tell You My Trans Journey From Female To Male & How That Has Affected My Desi Family

Lifestyle Jun 08, 2021

*We posted this story to celebrate International Transgender Day Of Visibility. We feel this perspective is so important that we decided to share it again with our global audience as part of our PRIDE 2021 Special.

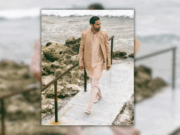

We head to South Africa where Jude Daya a transgender man with South Asian heritage shares his personal journey. Coming from the world of academia, Daya’s MA in Psychological Research focuses on transgender men and mental healthcare. He aims to train as a clinical psychologist and work with LGBTQIA+ youth and people with personality disorders. Today, he explores the sense of otherness and belonging, both in terms of culture/race/ethnicity and in terms of gender. Here is Jude’s story.

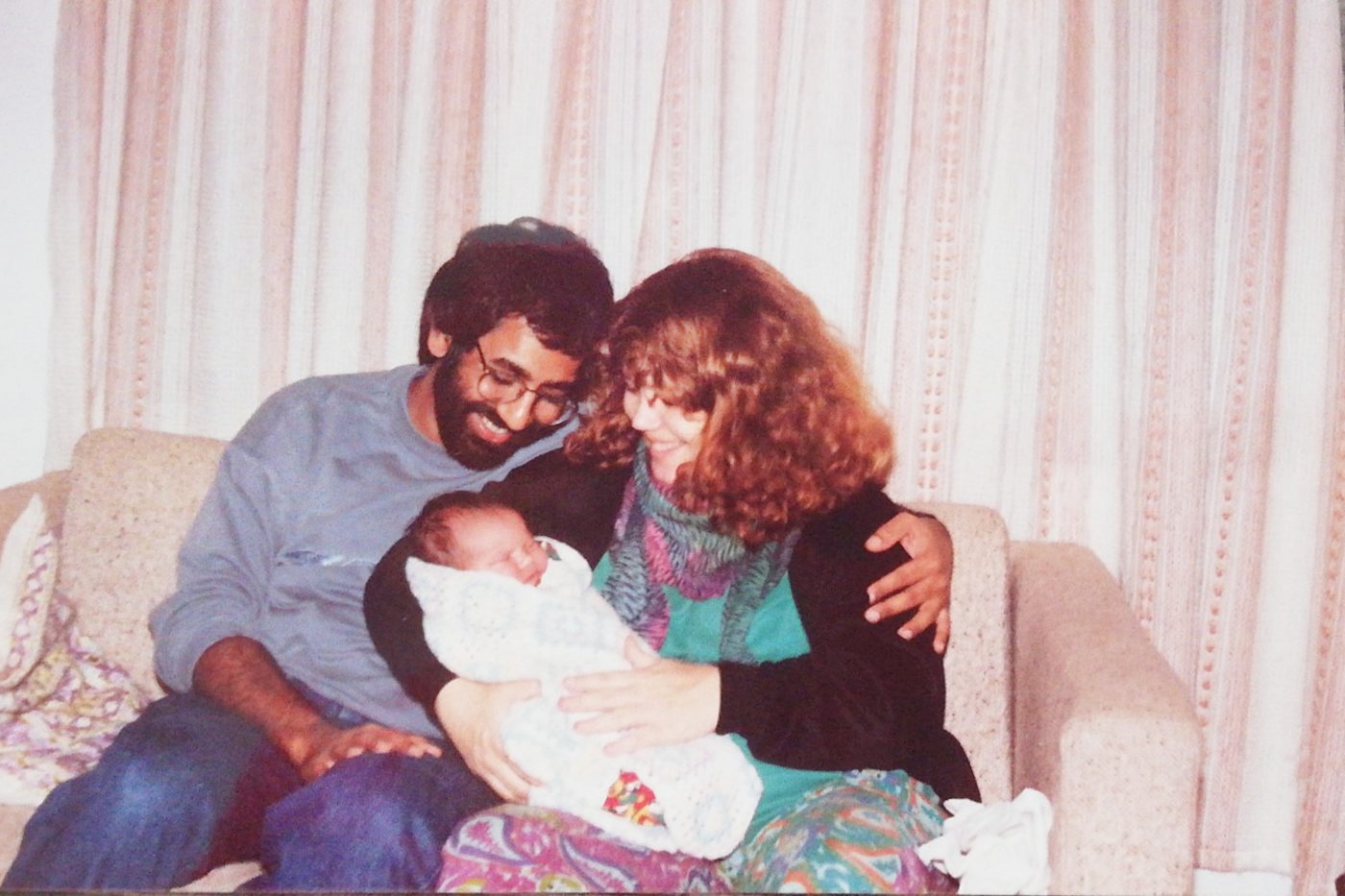

In June 1993, Pramod Daya and Fiona Adams welcomed their first and only child into the world: a daughter. The name they give her is chosen not only because it represents her Indian heritage but also because it will be easy for others to pronounce. For the next 24 years, every non-Indian person who meets Anjuli Daya will butcher her name or try to Anglicize it. This is the start of an ongoing conflict between one cultural identity and a world that does not understand it, that tries to interpret it through a White gaze.

My parents are not transphobic, but the popular media I encountered as a child was: the only times I would see transgender people were in sensationalist tabloid stories invariably focusing on “the surgery,” or trans women misrepresented as “men in dresses” on TV. It was a long time before I had any idea of what being transgender meant, and longer still before I knew that trans men even existed. I had no idea that I was part of this group, let alone that two decades later I would be researching what remains an understudied community.

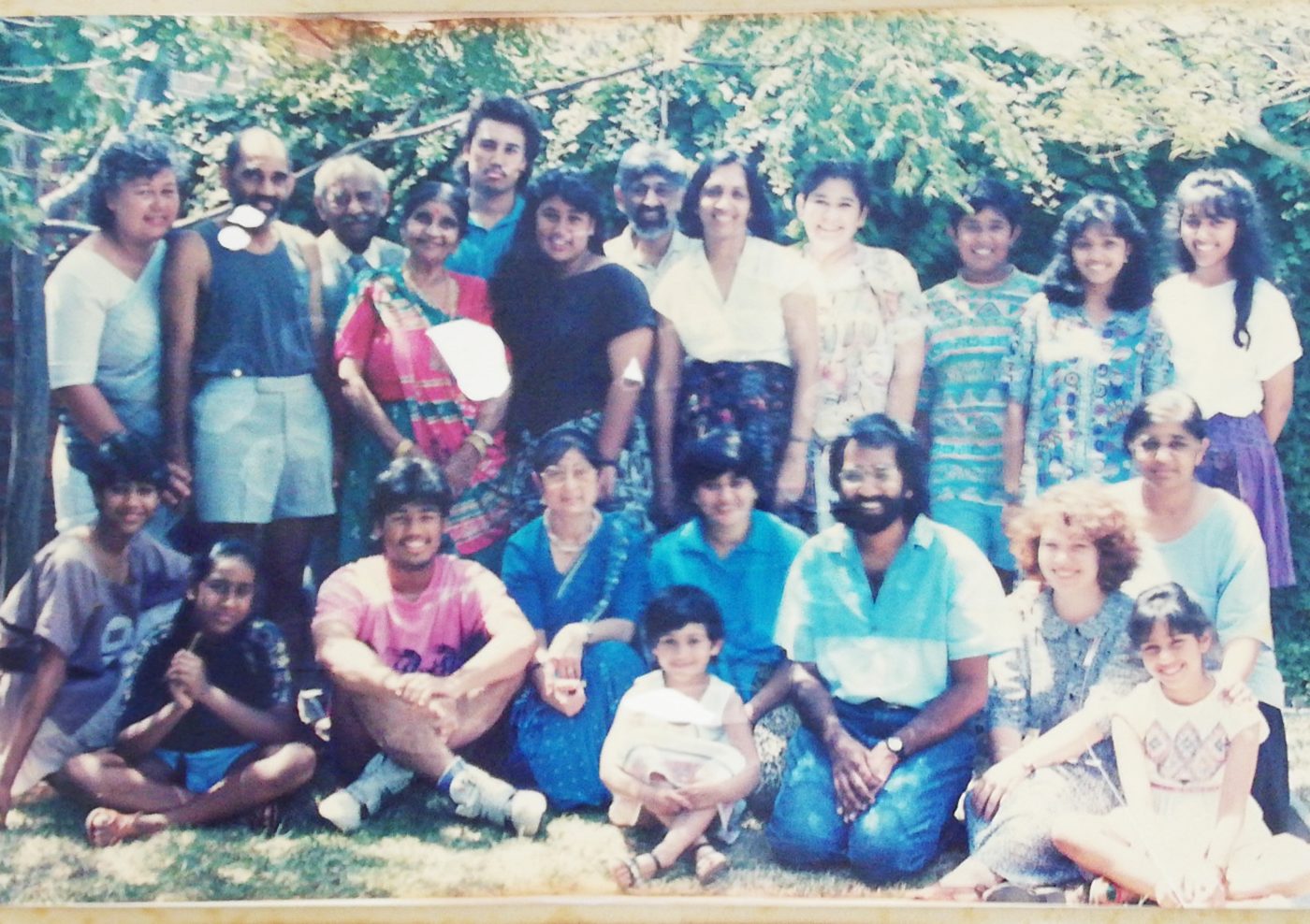

Representation and having the words to explain your experiences can make you feel less broken, less weird; however, I never saw anyone like me anywhere growing up. My parents were friends with another White/Indian interracial couple, but their son looked more Indian than White. I started out looking like a light-skinned Indian girl, but today I am a completely White-passing man. I’m in online communities of trans people, and Asian-mixed people — but nowhere for the intersection of these identities.

To an outsider, this is simply a sweet family photo. To me, it is bittersweet. My parents’ unwavering love for me is clear as day on their proud faces. And I wish I could tell you a straightforward ‘success story’ about a mixed-race girl who easily found her place in the world. But reality is never that simple, and neither is the ongoing juggling of dual ethnic identities — nor the profound mistake made by assigning me female at birth.

There are differences and similarities between the two sides of my family. My paternal grandparents had an arranged marriage; my maternal grandparents did not. Almost all of my father’s siblings had several children; I am the only grandchild on my mother’s side. Some things are more complicated. Although my mother was the first White person to join the Daya family — and not the last — she was not the first person of another race. My father was the first person of colour to join the Adams family.

I would never have addressed any of my grandparents by their first names. However, although they were always just Gran and Grandpa to me, I knew from childhood what my maternal grandparents’ names were; I only learned my paternal grandparents’ first names later in life, because everyone called my grandfather Bapuji or Dada and my grandmother Ma.

My parents started teaching me to read at age three or four. Our first family trip to India was in 2000, and the fourth Harry Potter book came out that year. I was a massive fan but only seven, so my parents thought that the 600+ page book was more than enough reading for a three-week trip. I finished it in the first week.

This was the start of an insatiable curiosity and desire for learning. The HP books are for children but contain many Big Words I needed help with. I was fascinated by all these new words, and even from this young age, relished being challenged intellectually, found learning new concepts exciting rather than daunting. This has been part of the driving force getting me to the point of doing Master’s, and what keeps me going when academic work gets overwhelming.

I am only seven or eight here, but the nightmare of puberty started one to two years later. It’s not an easy stage generally. But when most of the changes happening to your body feel alien and wrong, and you don’t understand why, it can be traumatic. Puberty blockers are medical treatments that stop the prepubescent body from developing testosterone or estrogen. I’m not sure they were available then, plus I didn’t know I was trans yet, but if I had been put on them then it would have saved me so much pain. Putting gender-questioning children on blockers isn’t harmful, and if they change their minds they simply start puberty a little late. But going through the wrong puberty can be distressing for trans youths, and many of those physical changes are irreversible.

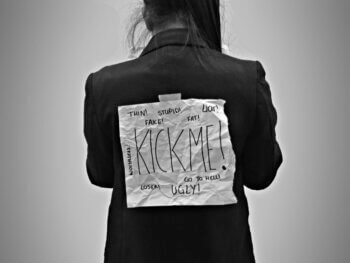

Although this was a decade before my legal name change and medical transition, to me, this is where Anjuli ends and Jude begins. At 13, I was still desperately trying to fit myself into boxes not made for me, identities that contradicted each other, never feeling like I belonged. On the one hand, not feeling Indian enough — even in a chaniya choli, bought on our second trip to India, attending an Indian cousin’s wedding, I felt inadequate. On the other hand, not White enough — not because of my mother, but because I didn’t fit White beauty standards, was too Indian to fit in with the all-White friend group I somehow ended up in. I had an “exotic” name and what one girl called a “natural tan”: Whiteness was a norm I couldn’t measure up to.

Then, I thought that I hated my long hair because it was difficult to manage. Now, I know I was experiencing gender dysphoria. The hair felt weird because it ensured I was seen as a girl. So the following year, the hair went. First in a series of progressively shorter bobs, until eventually in sheer frustration, I just went at it with the kitchen scissors. When I cut my hair, I cut off part of my life. I had moved to a boys’ school that had relatively recently become co-ed, wore the male uniform unquestioned, my hair was short, and even though I was still battling severe depression, I felt more like myself. Without long dark hair, however, I started looking less like my father’s family.

I had long since outgrown the children’s and YA sections of the local library, and by my mid-teens, I was reading things like neuropsychology textbooks for fun. I understood my interest in psychology as “wanting to understand how people work”. Maybe if I could understand other people, I could learn to be ‘normal’. But it wasn’t others I needed to understand as much as myself.

The next year, I moved schools again. If I followed the expected trans narrative, I should have known I was a boy since early childhood, been a total tomboy, or at least had some kind of eureka moment when I realized I was trans. Instead, I just remember that by age 15, I had found online support and resources, and trans male online communities. I started finding words to explain why I never felt right. However, even though I learned gender is not binary, I still felt societal pressure to fit within this dichotomy. ‘Woman’ was completely not me, and ‘man’ felt mostly right. But the online communities I had found were not without unhealthy messages: there was one way of being a trans man, and if you didn’t fit into that, you weren’t truly trans.

I did identify with parts of it: puberty felt awful, my body developing curves felt wrong, I wanted a flat chest, was never comfortable in dresses or skirts, and desperately wanted people to see me as a boy. But there were parts that I felt pushed into if I was to be ‘trans enough’, such as rejecting everything remotely associated with womanhood and femininity. The problem was, I’ve never strongly identified with traditional ‘macho’ masculinity either.

What I knew for certain was that I wanted to start medical transition as soon as possible, so that when I started university, I would be just another guy. So during high school, I came out to my parents. I am incredibly fortunate that my parents were accepting, that my main concern was that they wouldn’t understand. I did not fear what many trans youth still do today: being rejected, disowned and thrown out of the house. As understanding as my parents were, they did not, however, agree to my starting my medical transition before I was 18 and had left school.

In 2012, I started studying a Bachelor of Science at a university far from my home town. I wanted a fresh start, somewhere nobody knew me. The first two years, I stayed in university accommodation — residence, ‘res’ for short. However, there was no co-ed res, and although I was determined to stay in a male one, my parents vetoed the idea for fear I would be harassed or worse. Stuck in a girls’ res, in a small town with no access to trans healthcare, I grew despondent and doubted myself. I wondered if being trans was just a phase, and tried my best to be a woman. This led me to realize two things. I enjoyed some aspects of femininity, like wearing makeup. But I was not female.

My whole childhood I hated my name and spent hours on baby name websites in my teens looking for alternatives. When I was in undergrad, though, I realized that there was no way I could graduate as Anjuli. I searched for names again, looking first for a unisex or male Indian name that I could be certain nobody could mispronounce. Finding nothing that felt right, I broadened my search and chose Jude — yes, after The Beatles song. In July 2015, my legal name change was approved. I didn’t realize I’d signed up for endless “Hey Jude” jokes, but at least people say it correctly.

I wasn’t aware until much later that the reason my father had a problem with the name change was that he saw it as a rejection of my Indian identity. For me, this was about gender identity, not ethnicity; I am proud of my heritage.

After switching to a Bachelor of Arts, I completed undergrad in 2016: finally graduating as Jude Anjuli Daya. But I couldn’t do much with a BA in Psychology and English besides study further.

Back in my home town, I finally started the process of going on HRT (hormone replacement therapy) in early 2017. After a meeting with someone at a local trans organization, I was referred to the transgender unit at a local government/public hospital — one of very few such units in the country. I was assessed by three psychiatrists from the unit, a nerve-wracking experience to say the least, and was given a referral to the endocrinologist. I phoned every day for a week, but nobody answered. With the public system getting me nowhere, I tried the private route.

Through another trans male friend, I got the details of a different endocrinologist. In October 2017, I started Nebido testosterone. I am so grateful that I can afford this particular form of T (testosterone), one long-acting injection every 10 weeks — and that private healthcare is an option at all, since this isn’t the case for most South Africans.

Since there would be noticeable changes on T, I realized I had to come out to my extended family. Terrified of rejection, I sent the message in the Daya group chat. I already felt like the black sheep of the family, and this was yet another ‘different’ thing about me. They accepted me, with one cousin even asking about my pronouns. I may be different, but I still belong in my family.

I started studying again in 2018, this time through distance learning. As difficult as this was, it taught me self-motivation — invaluable for further studies. In 2019, I completed a BA Honours in Counselling Psychology — Honours is a postgraduate degree here, and a prerequisite for most Master’s programs.

But to become a psychologist in South Africa, you also need to complete a Master’s in Clinical Psychology. I couldn’t manage to complete the time-consuming applications by the May deadline — but there was another psychology MA option, which I applied for just in time for the October deadline.

In December 2019, I was officially accepted, and in February 2020 began a Master’s in Psychological Research. I had been thinking about potential thesis topics since undergrad but had too many options. With my supervisor’s assistance, I chose one: Transgender men and mental healthcare services in South Africa. I wondered if it was self-centered to choose a topic so close to home, but quickly realized its significance. Trans people are so often reduced to statistics about murder rates or suicide attempts, and there is a great need for research that looks at us as individuals with unique experiences.

South Africa is renowned for its progressive Constitution, yet this has by no means resulted in the country being an entirely accepting place. Many (if not most) trans South Africans still face prejudice, harassment and violence on an ongoing basis in many areas of life — including discrimination from healthcare providers. However, very little is known about mental healthcare treatment of trans individuals. I aim to contribute to knowledge in this area in order to help ensure trans people receive appropriate healthcare that is sensitive to their needs.

*Check out our article on 8 Ways To Support The Trans Community right here!

All Photos Courtesy of Jude Daya

Jude Daya

Author

Jude Daya (@MorticiasDad) is a transgender man from South Africa. His MA in Psychological Research focuses on transgender men and mental healthcare. He aims to train as a clinical psychologist and work with LGBTQIA+ youth and people with personality disorders.