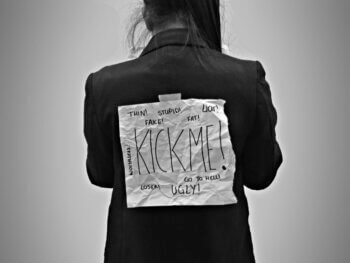

Fighting For The Invisible: My Chat With Renu Mandhane, Chief Commissioner Of The Ontario Human Rights Commission

Lifestyle Mar 04, 2019

I had an unique opportunity to sit down with Renu Mandhane, Chief Commissioner of the Ontario Human Rights Commission where we explored various forms of advocacy, including her work regarding correctional facilities and their treatment of women with mental health issues, fighting for the invisible and the power of the people.

When images of the Ethiopian famine flashed across her television screen in Calgary, a young Renu Mandhane immediately asked her father one question: “Why can’t we adopt kids from Ethiopia?” Her empathetic trait and acknowledgement for just causes clearly flourished from a young age.

Thanks to her family’s love for global travel, she was able to engage with various social and political perspectives which contributed to her foundation for justice through her various stages of school. With an LL.M degree in international human rights law from New York University in hand, Mandhane spent her early career representing victims of sexual violence and prisoners. As the Executive Director of the International Human Rights Program at the University of Toronto Faculty of Law, she also appeared in front of The Supreme Court of Canada and The United Nations. Fast forward to October 2015, when Mandhane was appointed as the Chief Commissioner of the Ontario Human Rights Commission.

Here is more on Mandhane’s mission.

Hina P. Ansari: You told me about your earliest memory of advocacy awareness was when, as a child, you asked about the children affected by the Ethiopian famine. What other personal and cultural experiences as a South Asian woman would you like to share that also helped form your advocacy perspective.

Renu Mandhane: My parents were immigrants to Canada. My dad came to Calgary in 1969 as a student. Obviously, there weren’t a lot of South Asian people so our cultural community was a big part of our lives as more people emigrated to Calgary. After my dad got married, both my parents were involved in the Hindu community of Calgary. I think I always felt that I was in-between two worlds which I now realize is common for second-generation Canadians.

From an early age, I was aware that I was different from my peers. I grew up in a suburban community where many of the kids hadn’t been outside of the Canada. My family, on the other hand, were traveling all of the world. I had a very different home life than most of my friends. I think just that sense of difference got me into social justice.

At the time, as well, I observed that South Asian culture, whether in India or in our diaspora community, was quite conservative. That always rubbed me the wrong way. I often found myself challenging expectations that some people in my community had around marriage and child rearing, for example. Now, of course, those differences are less stark in both India and in the diaspora community.

HPA: Tell me more about your travels and how that has played a part to form your specific perspective on justice.

RM: I think traveling really gave me a broader worldview and a realization that there was a world beyond Canada but also that there were really complex problems in the world.

Travel gave me the freedom to embrace and understand difference. When I was in undergrad at Queen’s University my parents took a job in Nigeria. They left Canada for ten years. That offered a whole other set of travel opportunities in Nigeria, Kenya and South Africa.

I did my last semester of law school in Singapore. From there I traveled throughout Southeast Asia. I went to Thailand, Malaysia, Vietnam, Laos and Indonesia. Singapore was an interesting place because it’s extremely clean, safe and beautiful.

I think a lot of people would think it was paradise but through studying law there, what I realized is how repressive the regime was in order to have this seemingly utopian society. They have some of the strictest drug laws in the world. That awakened the side of me that wanted to work to advance civil and political rights. I realized that I actually didn’t want to live in Singapore despite how convenient and easy life was for somebody like me because of the impact on my personal freedoms.

HPA: And that travel sensibility helped you when you were exploring the lesser-trekked Canadian areas as well.

RM: Actually, in my current role, I have done a lot of traveling within Ontario. I was most recently in Moose Factory, in Moosonee, along the James Bay Coast.

I remember thinking that some of these places were so unlike Toronto, almost like a foreign country. I’m relying on all the skills that I’ve developed in terms of cross-cultural communication and going with the flow. Being comfortable in uncomfortable situations. Some people don’t speak English, they speak Cree. The landscape is entirely different. I was thankful that I had those earlier travel experiences because without them I would be somewhat uncomfortable. I found a comfort zone but it was my foreign travel comfort zone. The travel has been a huge theme of my life and I want that for my kids too. We haven’t yet traveled all that much with them but I want them to get the travel bug early on.

HPA: Tell me about the mission of the Ontario Human Rights Commission.

RM: The mission is to both advance and promote human rights. To create a culture of human rights’ accountability. We have a promotion mandate. We write policies, provide training, teach people about how to meet their obligations under the Human Rights Code. We have a pretty active social media presence. We’re engaging with the community, in real time on human rights issues to provide guidance and support.

I think what’s unique about the Commission and what makes us different, is that we also have an enforcement mandate. We can initiate public inquiries and we can seek and obtain information. We can launch litigation before the Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario, and we can intervene on cases including at the Supreme Court of Canada.

So, while we always use the carrot first, the carrot is always more effective when you have a stick as well. We get to use these both of these parts of our mandate in a very unique and strategic way that allows us to have the impact.

HPA: Tell me about mandate of the Ontario Human Rights Commission.

RM: We have a statutory mandate. Our mandate comes from the Human Rights Code. Though, it has been reformed over time, the Code is almost 60 years old. Just to put that in perspective, this is one of the first human rights laws in the world. The UN Charter and the UN Declaration on Human Rights pre-date the Code, but the international conventions on civil and political rights, and economic, social, cultural rights, all come after the Code.

The Code is a foundation document. It was the first human rights code in Canada. Our mandate comes from the code and it draws heavily on international human rights law principles. It’s amazing to have such a wide mandate. You could do any number of things and never be short of work.

When I was appointed to the Commission, the breadth of the mandate was something I really had to wrap my head around because there’s a way of doing this work where you’re completely reactive. You’re just reacting to one fire after the other—and trust me, everyday there’s ten—but what I really wanted to do was shift towards more proactive work.

HPA: In 2016, under your leadership, you launched your first strategic initiative: a five-year plan which prioritizes criminal justice, reconciliation, poverty and education. Tell me about this action and why focus on those areas?

RM: We picked those areas because we consulted with [approximately] 300 individuals across the province. What was so amazing is that people were able to put their stakeholder groups discrete issues aside – whether as a Black person, an Indigenous person, or as a woman – and identify those broader social systems where many marginalized groups face discrimination and barriers to advancement.

There was a remarkable consensus around these four areas. That’s why we decided to take a more sectoral approach. And because the last provincial government was focused on reforming policing and corrections, that’s where we focused a lot of our energy over the last year and with remarkable success.

We just crunched the numbers and nearly 70% of our recommendations were accepted by the government. I think that having that focused approach allows you to push that boulder up the hill a bit quicker and I think we are starting to see the impact of going deep on some key issues.

HPA: You’ve been active with respect to mental health issues especially with female inmates. Please tell me more.

RM: Before I was appointed, the Commission had established itself as a leader in mental health. Past Chief Commissioner, Barbara Hall focused a lot of her time on this issue. The Commission was part of the real push to have mental health understood as a disability.

I know when I was doing this work, even back in 2010 (Mandhane wrote an op-ed for The Toronto Star about the tragic circumstances in the death of inmate Ashley Smith the same year), people were not talking about mental health as a disability. I think the Commission was ahead of the curve on framing mental health as a disability and as a human rights issue. My own work intersected with the Commission’s work around corrections.

My own journey in relation to corrections started when I was a criminal defense lawyer. I had the opportunity to work with prisoners who were federally incarcerated and mostly women. I, along with a more senior lawyer, represented a group of women who challenged the closure of a minimum security federal penitentiary for women, the only one at the time in Canada. Through that, I got to know Kim Pate, now Senator Kim Pate, who was then the Executive Director of the Canadian Association of Elizabeth Fry Societies (CAEFS).

Kim and I kept in touch over the years and it was the work we did together that resulted in a report—while I was at University of Toronto—on the treatment of federally sentenced women with mental health disabilities. The goal of that report was to take the Ashley Smith case which had struck a chord with the public at that time and demonstrate how Ashley’s treatment was not atypical.

HPA: I remember that case well and how the issue of mental health in correctional facilities was under the glare of the national media.

RM: This was the first time we were talking in the public square about corrections, about women and about mental health. I remember when those videos of Ashley’s horrendous treatment came out, people who had heard me talk about this for years, said, “I finally get it. I don’t know that I actually understood what you were talking about until I saw those videos.”

I think the goal of our research that Kim Pate and I did at University of Toronto, was to highlight the fact that the treatment of Ashley Smith was systemic and it was a natural product of the way corrections handles people with mental health disabilities. While the result was tragic, it was a predictable result based on the practices that were being used. People want to believe that an extreme case does not represent our society or how we treat people in crisis.

The goal of this report was to say, “This is exactly how we treat people with mental health disabilities in corrections.” We disproportionately use solitary confinement. Women tend to be classified as high risk because of their histories of abuse and as survivors of abuse, or because they are Indigenous.

Out of that I started to become very interested in corrections and I think it was a culmination of a lot of things. I have a fascination with invisibility. The idea of people who are part of our society that we as a society choose to make invisible because it’s more comfortable and because they don’t have a voice for themselves.

HPA: With your focus on “the invisible” combined with mental health and correctional facilities, you must come across some eye-opening cases.

RM: I think the intersection of marginality and mental health comes together in the correctional setting. When I came to the Commission, I was already primed to care about these issues because I’d worked on them for a long time.

Prior to my arrival, the Commission [negotiated] settlement in the Christina Jahn case which involved a woman who was kept in solitary confinement in the Ottawa-Carlton Detention Center for more than 200 days. I remember being briefed on the settlement and one of the terms of the settlement was that provincial corrections wouldn’t put people with mental health disabilities in segregation or solitary confinement except in the most exceptional circumstances.

Well, I had just done this research on provincial corrections while at the University of Toronto and I get briefed on this file as incoming Chief Commissioner and my gut was just like, “They are not following the settlement.” I’ve been in these facilities; I’ve met these people. This just doesn’t accord with the reality that I’ve seen first-hand.

At the same time, the government was doing a segregation review. We started visiting correctional facilities because nothing sends a stronger signal than just showing up and saying, “Hey, I’d like to take a look.” I also knew that almost no one has access a correctional facility. Journalists don’t get access; community activists don’t get access.

Really, it’s the lawyers who get access and people in positions like mine. I felt that it was important to start having a presence in these facilities and opening myself up to hearing people’s stories. I have tried to bring that grassroots approach to a lot of our work at the Commission.

You can’t understand these issues unless you engage with individuals because systemic issues are individual and individual issues are systemic. They’re not two different things and travelling to these correctional institutions was part of trying to get the Commission into the center of where things were happening.

HPA: In your experience, do you find that the awareness of human rights issues, is so front and center now, then it has been in the past?

RM: The issue of sexual harassment is an amazing example of that. Sexual harassment has been illegal for decades but it only became socially unacceptable through the #MeToo Movement. That’s when we started seeing companies hold their own CEOs accountable. Previously, that would have required someone to file a complaint, to go through a huge legal process and then, basically force their employer to act.

On the flipside, we are also seeing more polarization. As equity seeking groups become more vocal, they face those who want to maintain the status quo at all costs.

HPA: The public voice is essential.

When the public echoes our call for justice and equality, that’s the game changer. We can be writing a policy, we can be advocating in court and see a marginal gain but when the public demands accountability, that’s when we just see these leaps and bounds.

Main Image Photo Credit: Michelle Girouard/ The Ontario Human Rights Commission

Hina P. Ansari

Author

Hina P. Ansari is a graduate from The University of Western Ontario (London, Ontario). Since then she has carved a successful career in Canada's national fashion-publishing world as the Entertainment/Photo Editor at FLARE Magazine, Canada's national fashion magazine. She was the first South Asian in...