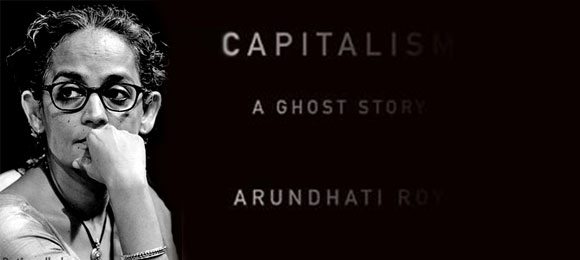

Roy’s Latest Non-Fiction Examines The Dark Side Of Democracy In Contemporary India

Arundati Roy is an Indian author and political activist widely known for her seminal novel, The God of Small Things (1997). To add to her intellectual repertoire, she has also been involved in human rights and environmental causes and has written widely about climate change, war and the dangers of free-market economical development in India. She has defended the marginalized and the poor who are caught in the middle of all the chaos and who are overlooked in the larger schemes of economic and social development in contemporary India.

Roy's latest non-fiction book, Capitalism: A Ghost Story (2014), is a must-read. Admitting to readers that her book might be a “harsh critique” of capitalism, she writes that capitalism is like a sorcerer’s apprentice working to magically draw forces that are overwhelming and difficult to control. These "apprentices" are multi-national companies, which she says cause rifts and disruptions to the world’s cultures, governments and economies.

She mainly denounces the Ford, Rockefeller, and Carnegie foundations, which have been responsible historically for creating what she calls “global corporate governance” in the 1920s. This led to the development of the most powerful foreign policy measure groups in the world, including the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR), which was later funded by the Ford Foundation as well. Then, the CIA, UN and the Research and Development Corporation (RAND) were products of the grants and funding that these foundations supplied. Many years later, Roy observes, this idea trickled down to India and Bangladesh with the Grameen Bank and the concept of microfinance. Roy argues that microfinance has been “responsible for the hundreds of suicides — two hundred people in Andra Pradesh in 2010 alone.”

The book scrutinizes the ways in which Indian politics have built a capitalist model mirroring the US. In Roy's eyes, this has been nothing but damaging to the poor, marginalizing those who have been victimized. 250,000 farmers have committed suicide, while 800 million Indians have been impoverished and dispossessed due to environmental destruction.

Roy underscores three startling concepts: poverty, feminism and the "NGO-ization" of the women’s movement. These topics were of interest to me especially in terms of my scholarly work and research.

Let me begin with Roy's critique of poverty. She cites that poverty, like feminism, has been often seen or understood as an “identity problem.” For me, it was interesting to note that she used Danny Boyle’s Slumdog Millionaire (2008) as an example of arts that problematically create an “exotic identity” of the poor. This identity shows the poor as resilient, with fighting spirit, and able to overcome their lives' challenges.

I agree with Roy about the way in which poverty has been romanticized — especially in films such as Slumdog Millionaire. She also makes a powerful point, questioning why the rich aren’t examined in the ways poor communities and their people are judged or understood. I couldn’t help but think of the Dharavi slums in Mumbai, where the poor and forlorn are shown by media as survivors and ingenious entrepreneurs working through their daily lives (in other words, "Oh! Their lives aren't really that bad.").

Roy also criticizes the feminist movement in India for being borne out of Western liberal feminism. She cites the foundations of financial support for women’s movements in India in the 1960s and '70s. She distinguishes between the urban and rural women’s movements in India. While most radical, anti-capitalist movements were located in rural cities, she suggests, urban Indian women (who have joined movements such as the Naxalite movement), have been greatly influenced by Western feminism. Roy draws connections between the women’s movement and NGOs that have been responsible for defining "feminism" based on the amount of funding received by each NGO.

While there may be some truth to her observation, considering her intellectual and political status in India, I do think that the feminist movement in India is more complex and nuanced. There are still women who lack property rights or reproductive rights (in the case of surrogate mothers). Class perhaps does play a role in shaping the women’s movement in India, but it's hard to create an absolute distinction between class and gender because the gap between the poor and rich is so wide but women face many issues across caste and class boundaries.

Roy's non-fiction book draws a compelling anti-capitalist critique that explores capitalism's effects on poor and marginalized people in India. I think it’s a great book to read — especially as we think of India as the world’s next great economy after (or before) China.

Feature Image Source: Current Books

Nidhi Shrivastava

Author

Nidhi Shrivastava (@shnidhi) is a Ph.D. candidate in the English department at Western University and works as an adjunct professor in at Sacred Heart University. She holds double masters in South Asian Studies and Women's Studies. Her research focuses on Hindi film cinema, censorship, the figure o...