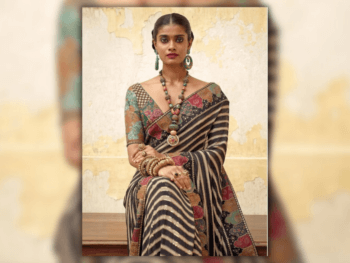

Every tattoo tells a story of artistry, culture and identity.

The first time I told my mother I wanted to get a tattoo was halfway through my first year of university. I wanted to do something to mark what was supposed to be this life-altering experience. Her reaction? Confusion mixed with disbelief and amusement. She wasn’t thrilled, but she didn’t refuse. I had already picked a design, but then something happened. I changed my mind, not once but several times. Did I really want to permanently mark my body? What would my traditional Indian relatives think? What would my perfect future husband and kids think?

I imagine that other young South Asians have gone through a similar thought process. Tattoos are not uncommon. According to a study financed by Health Canada in 2000, eight per cent of Canadians aged 12 to 19 have a tattoo and an additional 21 per cent indicated the desire to get one. Since 2000, these numbers have continued to rise. But despite their growing popularity, tattoos are still a grey area — a speck in the larger debate of merging traditional Indian values and customs with more liberal western practices.

Roots in cultural body art

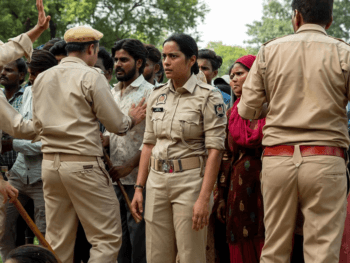

Today’s tattoos modify the body by inserting pigment under the skin. However, tattoos have ancient roots that started with cutting the skin to achieve scarring. Historical recounts of many cultures have revealed forms of tattooing that served various purposes, from devotion to rites of passage to means of identification. Body art can even be found in the roots of our own South Asian culture. Older women of the Rabari tribe living mainly in Rajasthan, Gujarat, Haryana and Kutch often have designs imprinted on their hands, necks, legs and even dots on the face — markings they believe to be magical.

A cultural and generational gap of sorts

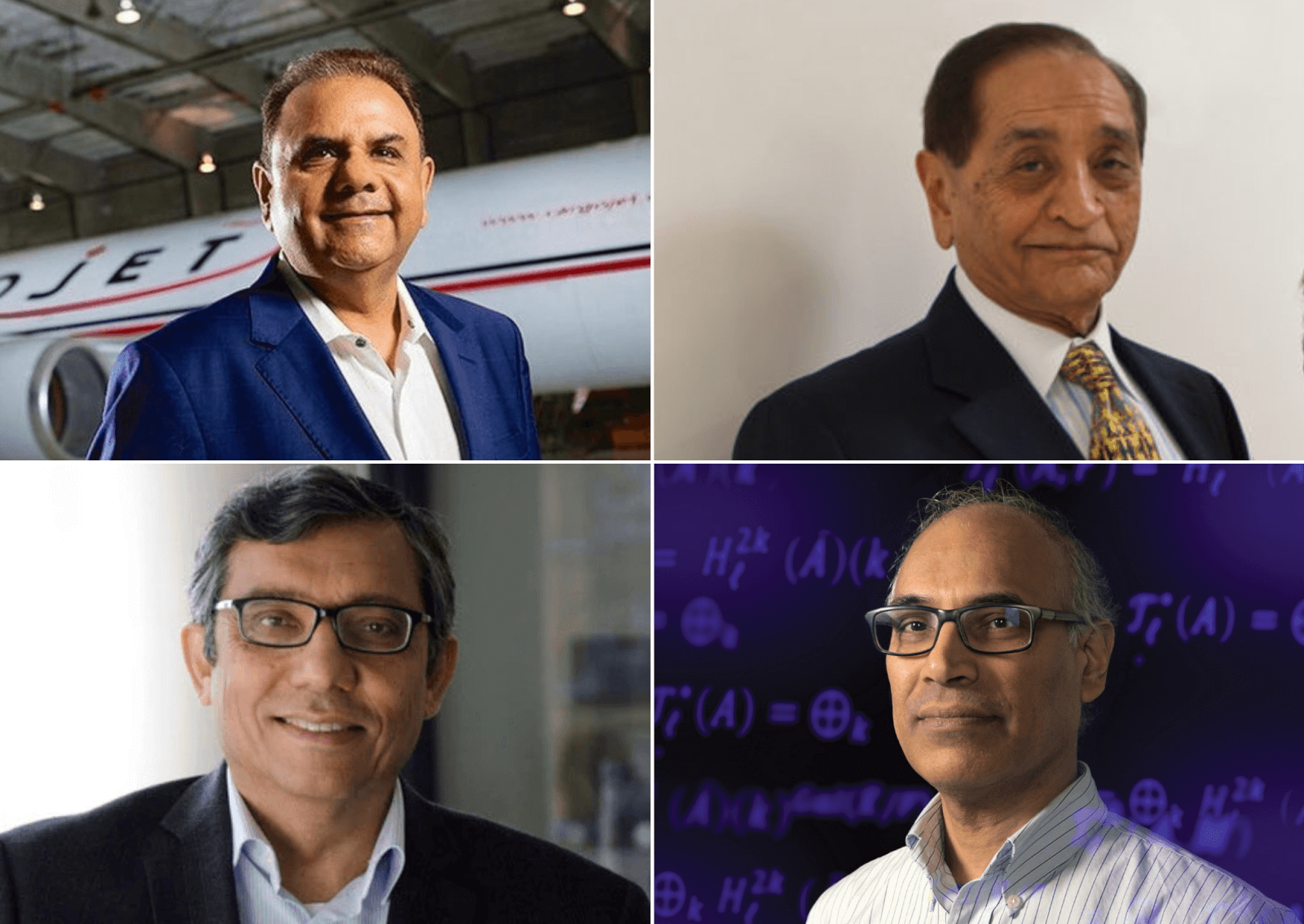

The tattoo culture on our side of the world is strikingly different from the villages of rural India. Somewhere between there and here, tattoos became denigrated — something reserved for young defiant troublemakers and dangerous jailbirds. But over the past decade, tattoos have resurfaced in mainstream culture, adorning the bodies of college students, middle-aged parents and CEOs alike. Many argue that this growing visibility of tattoos on people of all ages, races and social circles means they’ve become more socially acceptable. It seems logical, but is it true?

Dr. Sachit Shah is a family physician in Surrey, B.C., and his clinic, Beautiful Canadian Laser and Skincare Clinic, specializes in laser tattoo removal. He has seen removals for many reasons, from prison and gang markings to conservative mothers-in-law demanding that their new daughters-in-law have their tattooed past erased. “I’ve even got a subset of patients who have ended up getting good jobs,” explains Shah, “but as they get up their career ladders, there’s a feeling that they cannot progress if they have visible tattoos.”

Feelings are mixed for young South Asians in North America. They don’t see anything wrong with tattoos but don’t think their parents feel the same way.

Nineteen-year-old Ammar Dayani, born in Montreal and raised in Toronto, has three tattoos: a parent’s name on each shoulder blade, with a rose around his mother’s. He got them to celebrate everything his parents do for him. “Most people think I only got my parents’ names because it would be a good excuse to get a tattoo,” says Dayani. “But I put a lot of effort into thinking about what I wanted, when I wanted it and where I wanted it.” Both of Dayani’s parents supported his decision to get inked, but everyone isn’t that lucky. “Most South Asian parents are old-fashioned, which is why most parents don’t have tattoos and don’t let their kids get tattoos, because it ‘ruins’ your image.”

Saima Ali*, 23, got her first and only tattoo last year. Despite knowing that her father would never allow it, she wanted to get something to symbolize the most important people in her life and the beliefs that they’ve taught her. Her father still doesn’t know about her tattoo. “As a Muslim, getting a tattoo is completely frowned upon. He believes altering the body God gave us is a sin,” she explains. She credits her decision to get the tattoo anyway to “personal choice and differences in beliefs.”

The missing link

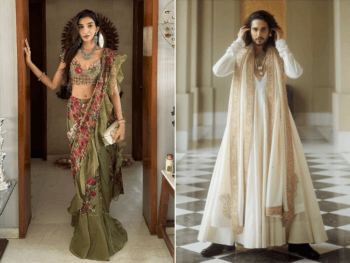

Body art in parts of India is not only accepted, it’s expected and even celebrated. But it’s not the same in North America; the missing link in merging cultures and lifestyles is the significance of the tattoo. When the industry gained momentum in the 1990s, the trend was to walk into a parlour, pick a design and have it done on the spot. Today, the tattoo industry is undergoing another transformation, taking it back to cultural roots. Ion Nicolae, owner of Toronto’s trendy Black Line Studio, has seen proof of this evolution. “People are a lot more educated these days. They’re putting more thought into it and the flow of the industry has gone into custom art. Requests are getting more and more intricate.” According to Nicolae, people are going big with custom designs like sleeves and full backs. But this trend isn’t unique to Canada. Lokesh Verma, the owner of Devilz Tattooz in New Delhi, says, “In the past two years, a lot of people have started to give more thought to their ink. People are getting more meaningful things done — things they can relate to.”

Tattoos as personal markers

Ashnoor Kanji of Edmonton, Alta, is a prime example of someone who uses tattoos as a way of marking her history and the struggles she has overcome. Her first one is of a celestial sun with the yin and yang symbol in the centre. “The sun represented a new beginning and the yin and yang represented balance, so essentially, a new beginning of balance and equilibrium in my life,” she says. Her second tattoo, which she had done earlier this year at the age of 35, is Arabic calligraphy meaning “In the name of Allah, the most beneficent, the most merciful.” Explains Kanji, “My faith and my God have been my guiding beacons through some very difficult times.”

Because tattoos modify the body, they may never become entirely acceptable. But people seem to be getting it. Tattoos have to be personal and meaningful. Today, they’ve become more than just body art. They’re not just a symbol but also a statement, an extension of what makes a person who they are and who they hope to become.

I’ve decided to shelve my tattoo plans for now, perhaps until I find something that I feel best incorporates, represents and celebrates my Indian-born-Canadian-desi life. My mom agrees.

BY SORIYYA BAWA / PUBLISHED IN THE FASHION, STYLE & HOLIDAY ISSUE OCTOBER 2011

*NAME OF PARTICIPANT HAS BEEN CHANGED