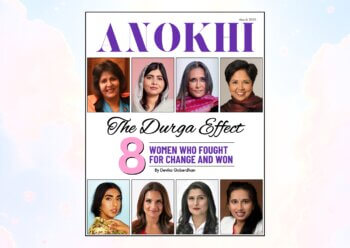

A CULTURAL CATASTROPHE?

For ten years, I was married to Deepak. Not one night of happiness…He used to beat me up…He used to have affairs with other women…Sometimes, sometimes, he used to rape me…For ten years, I lived a life of beatings and degradation. I came out of my husband’s jail and entered the jail of the law. It is here that I have found a kind of freedom.” – Provoked (2007)

These words are uttered by Aishwarya Rai-Bachchan in the film, Provoked. The actress plays real-life domestic abuse victim, Kiranjit Ahluwalia, who was given a life sentence for murdering her abusive husband in 1989. She was ultimately freed by the British judicial system in the landmark case, Regina vs. Ahluwalia that redefined the word “provocation” in cases of battered women. She was reunited with her children and subsequently given an award by the wife of former Prime Minister Tony Blair for her crusade against domestic violence.

Consider Ahluwalia’s words for a minute. Imagine how terrifying her life with her husband must have been for her to have considered jail as a place of freedom. Domestic violence is a tragedy that many women face, but as many South Asian women’s organizations have found, it is made even harder with the difficulty many people have in acknowledging its presence in the South Asian community.

First we must recognize the obvious: women’s rights are human rights. Like everyone else, women have the right to a safe home, a loving relationship, and the freedom to make their own choices.

But there have been many cases of domestic violence in the South Asian community in the United States, Canada and United Kingdom. Amandeep Kaur Dhillon was just 22-years-old when she was stabbed to death by her father-in-law on New Year’s Day 2009. Dhillon was prevented from seeing her family, her friends, and even going to the gurdwara to pray. The Brampton, Ontario woman was to be her Punjabi family’s ticket to a better life in Canada, but demands over dowry ensured that would never happen. Instead, her family had to desperately apply for emergency visas three years after her marriage to attend her funeral in Canada.

She worked at the Dhillon family grocery store with little private time for herself. Whenever she called home to India, someone always listened on the other line. Her aunt claims that conditions for Dhillon worsened after her mother-in-law moved in. The only joy in her life was her little boy, Manmohan, born on March 1, 2007. But even that happiness was stolen from her when he was sent to live with her mother-in-law in India.

Dhillon continued to sacrifice herself. Even after the wedding, she was told her immigration papers would be filed only if her parents gave them another 100,000 rupees or $2,500, which they did. The poor young woman saw no way out. She feared her baby would never be returned to her if she complained and knew the hopes of her own family rested on her beaten shoulders. In the end, time ran out for Dhillon that New Year’s Day. Her father-in-law, 47 year-old Kamikar Singh Dhillon has been charged with first degree murder in her slaying.

37-year-old Aasiya Hassan fared no better. Her murder is a crime is rife with brutal irony: a woman decapitated by her estranged husband in the offices of the television network the couple founded with the hope of countering Muslim stereotypes. Muzzammil “Mo” Hassan, the founder and chief executive officer of Bridges TV, a Buffalo, NY based Islamic television Network, admitted to police that he had beheaded his wife after she had served him divorce papers. He was only charged with second-degree murder for this gruesome act.

Honour killings, dowries, misogyny, and patriarchal families. What can we do and how can we prevent it from happening to our loved ones—our sisters, daughters, nieces, aunts and mothers? These are tragedies that begin at home with their husbands, fathers, brothers and uncles. Often, when the abused victim does reach out, she is quickly sent back to her husband’s family. The underlying assumption here is that she is beholden to her husband’s family and is better off with them than alone. But these cultural practices can often lead to catastrophes.

Such women often live under constant threat of sexual harassment, sexual assault, and rape, in their own homes and from men they know. In most South Asian societies, the responsibility of maintaining standards of sexual ‘purity’ and ‘honour’ are imposed upon women. Thus, it is often the victim and not the perpetrator who bears the burden of shame and guilt. Consequently, women are often hesitant to report the crime. Many women are afraid to complain. "Once you come out in society and complain about abuse, police and the neighbours see you differently. You're a victim, but they will victimize you more," says one survivor who does not wish to be named.

Dr. Amritpal Singh Arora conducted a study at the University of British Columbia in Canada examining the barriers surrounding domestic abuse among South Asian women. He approached various women’s agencies and gained their cooperation of 11 South Asian women between the ages of 24 and 54 who were either still in an abusive relationship or who had left. “Although the impact of domestic abuse on a woman’s health has been well documented, the impact on South Asian women has not been thoroughly investigated,” says Arora. “I wanted to find out what more family physicians can do to address this issue in our community.” He found that when victims of abuse approached their family physicians, the tendency was to swiftly prescribe medications without delving into the cause of their chronic complaints. When the participants did confide in their family physicians, the women were frustrated at divorce being presented as the only option. “We need to present realistic options to these women, like counselling and women’s networks who deal with such issues.”

One such organization that specifically helps South Asian women in need is Sakhi for South Asian Women, a community-based organization in the New York metropolitan area committed to ending violence against women of South Asian origin. They handle requests and arrange counseling for women who come to them for help. They also run national advocacy and research programs to expand awareness of the prevalence of domestic violence.

Over the past seven years, Sakhi’s call volume has more than tripled. In 2001, it received 201 new requests for support, compared to 731 requests in 2008. Purvi Shah, Executive Director of Sakhi says, “This data does not mean that the prevalence of domestic violence is increasing. Rather, it shows that people are realizing that they do have options when it comes to domestic violence, and thus, accessing information and seeking support. In fact, we know Sakhi’s community-based approach has been successful because we have noticed a marked trend of more men reaching out not only for information for themselves but also to marshall resources for women in their lives including sisters, nieces, and aunts.” The most important step in combating domestic violence is recognizing that violence is not acceptable, irrespective of religion or cultural expectations. “Many of the women at first blamed themselves. They felt that they were somehow at fault for provoking abusive responses by their partners. As the abuse continued however, most of them realized that they were not to blame and that they did not deserve to suffer. This realization was important as it allowed them to begin to take action,” says Dr. Arora.

Even though leaving their partner may eventually be the answer, it may take time for a woman to come to this realization. Women in abusive relationships need to feel that they can survive on their own. Many want to try to work on their relationship and resolve the issues. A man who is physically or emotionally abusive may be willing to find ways to change his abusive behaviour. Amandeep Kaur, who is a survivor of domestic abuse and now works as a Manager at Punjabi Community Health Services in Brampton says, “We have to take a holistic approach. If the woman cannot leave her abusive home, then we need to find an alternative plan for her.” Kaur goes on to add that in such cases, the PCHS encourages the whole family to come to the gurdwara for services such as senior and youth programs where the abusive partner is not directly confronted. Rather, the focus of these services is to explicate the negative influence of domestic violence on children and how it damages their personal growth. “This method has been quite successful because then the whole family is involved,” says Kaur. “It’s never too late to seek help, and it’s only the woman in the situation who says when it’s time to call in the police. That happens when her safety and the safety of her children is on the line.”

There is a growing demand for resources to support the victims of domestic violence and Shah believes this is a huge step for the South Asian community as a whole. Twenty years ago, it was a challenge for the community to even acknowledge that domestic violence was an issue in the community. What’s more, eight percent of Sakhi’s new requests in 2006 came from men compared to nearly 13% last year. “This is truly amazing. Given that Sakhi is working for a day when we no longer need to exist because there is no violence. To see men seeking help to make a difference in their families is a positive step towards our community working together to end violence,” says Shah. “And this makes the point clearly that domestic violence is not a women’s issue but a community issue.”

BY: TAMARA BALUJA / PUBLISHED: SUMMER 2009 ISSUE