Peeling back the shimmery Bollywood layers, we take a closer look at the industry's beauty double-talk

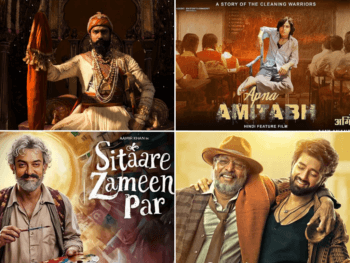

"Amitabh Bachchan is the one and only rare example of an actor’s career spanning more than three decades and still going strong,” says journalist, screenwriter and Bollywood insider Devansh Patel. This is the crux of the matter, as when the Big B (as he’s popularly known) joined the film fraternity, he was criticized very harshly for his tall, lanky, dark-skinned looks. Although his talent was undeniable, his looks were not appreciated. Yet today, he is a brand ambassador for so many campaigns, his voice and face are known even in remote parts of Africa. Similarly, superstar Rajinikanth from the South, who commands a massive fan base in Japan, is a dark-skinned, not-so-tall man who acts with India’s best-looking women and commands one of the highest salaries in Indian cinema.

Patel speaks of this contrast between looks and talent and ultimately, longevity: “No one understands who works and who doesn't,” he says. “It's the time of your arrival, it's the way you market yourself, it's the way you socialize and it's the way you choose to climb the ladder. Actresses have come and gone, but the mix of talent and beauty, like that of Jaya Bachchan, Hema Malini and Rekha, has remained forever. But sadly, our audiences are more inclined towards actresses and their looks than real talent, and filmmakers cater to that.”

The Indian film industry has proven to be fickle in its behaviour towards its actresses, many of whom start working in their teens — Neetu Singh was 13 when she first appeared on screen with now-husband, Rishi Kapoor. The shelf life of these women often extends only until their late twenties, and even then, many have very ornamental roles that are contradictory to their talent, which only a few good directors bring to the forefront. Very few actresses are given their due, in stark contrast with Hollywood, where actresses are often allowed to conquer their roles and get due respect on screen. The beautiful Natalie Portman, for example, will have her Black Swan, while Nargis was given a meaty and poignant role in Mother India. But in modern day cinema, this type of role is rare indeed.

Dr. Naman Ramachandran, renowned journalist and author of one of Bollywood's most comprehensive books, Lights, Camera, Masala, speaks about one of the ugliest truths of the cinema industry: “The casting couch is the darkest side of the industry. Alas, though people deny it till they are blue in the face, it still exists — for both men and women.”

Ramachandran also speaks frankly about models-turned-actors who have tried to make it on their looks alone: "Upen Patel tasted success only in modeling. Once he turned to acting, the audience quickly realized that he is merely a beefcake without an iota of acting talent and a strange accent to boot. He sounds neither British, nor Indian, merely illiterate.” This is in contrast to John Abraham and Arjun Rampal, who choose diverse roles to avoid being typecast.

When asked about the true meaning of beauty in Bollywood, Ramachandran is again to the point: “It is important for women to look good of course, unless you can make up for the lack of traditional good looks with acting skills like Konkona Sen Sharma. For men, they can escape with being plug ugly as long as their parents are senior industry people.”

Another worrying effect is that top heroines are not averse to just showing skin and looking good for item songs in films, something actresses like Helen in the North and Silk Smitha in the South did in the past. They allow themselves to merely decorate the film with a female presence, as opposed to demanding meaty roles. A very recent example is Katrina Kaif, with the very raunchy “Sheila Ki Jawani” in Farah Khan’s Tees Maar Khan. Kaif didn't speak a word of Hindi when she joined the industry and though she is learning, her body and face were her ticket straight into working with top actors from day one.

This objectified “item girl” phenomenon is examined by Ramachandran: “People like Malaika Arora Khan have made successful careers by just being item girls. But they are a rare breed, because most heroines are willing to do the same things that these item girls do. Regarding being well-known through objectification, most of these item girls are there in the industry for fame and since they achieve it, it must be satisfying work. More people in India give Malaika adulation for a “Munni badnaam” or a “Chaiyya Chaiyya” than if she were a heroine.”

Asad Shan, filmmaker, TV presenter, actor and head of the Iconic Bollywood Acting Academy in London, England, speaks about the unconventionally good-looking actors that do well outside of India: “People like Irrfan Khan (Slumdog Millionaire, The Namesake, A Mighty Heart) succeed because they play real-life characters the Western audiences can relate to and believe.” Shan goes on to speak about his experiences with the real ugly side of the industry in Mumbai: nepotism. “Nearly every movie star’s a ‘star son or daughter,’ and directors are not appointed by producers because of their talent, but for which star they are close to and who they can easily rope in. I don't blame the producer as they need to make their money back and audience relates to star power, but things have changed. The consumer and audience have changed and now content does matter. Recently, many big star movies have bombed and smaller films are decent bets due to the supply and demand of more Westernized, urbanized audiences making a huge shift.”

Englishman Steven Baker, the self-proclaimed “Bollywood gora,” is a prolific journalist who shares time between Delhi, Mumbai and the UK and shares his knowledge of the industry: “For a female to make it in Bollywood, looks supersede talent, which is why models-turned-actresses like Katrina Kaif and Deepika Padukone, will get parts in big projects where the way they’re presented is more important than their acting abilities. Stars like Tabu and Konkona Sen Sharma, who are perceived as unconventional, would still be judged as beautiful by most people's standards,” says Baker. “For men in the film industry, I feel that there are different expectations for the male 'star' compared to the male actor. The star, even in his forties, is expected to display a gym-bodied six-pack aestheticism. For male performers who are viewed as actors (Om Puri, Naseeruddin Shah, Nana Patekar, Anupam Kher), looks are not a factor. It seems as though there is a gender imbalance at play when it comes to gender and beauty in Hindi films.”

Baker discusses the skin-lightening fascination within Bollywood, especially as he has played roles in films like Dostana and Kismat Konnection and seen it first hand: “There is a definite 'dark side' to Bollywood, and that of course is connected to skin tone. Female actors are consistently expected to be lighter-complexioned than their male co-stars, and directors will use any means, from make-up to lighting techniques, to present the leading female heroine as fair. What is particularly interesting about Bollywood is that the actors we see on the screen are not representative of most of the population of India. This may be partly to do with the heritage of many acting clans from the pale-skinned, light-eyed region of Peshawar, or the use of fairness creams; compare a ‘90s Shah Rukh Khan or Preity Zinta to their more recent avatars and you will see what I mean.”

Back in the late 16th century, Shakespeare wrote that “beauty is bought by judgment of the eye” in his comedy Love's Labour’s Lost. This is a sentiment that rings true with every passing day, especially in Indian cinema.

BY ASHANTI OMKAR / PUBLISHED: THE LIVE BEAUTIFUL ISSUE / MARCH 2011