Contrary to the controversial preference for a son in other parts of South Asia, in Bangladesh, the girls are getting quite the status upgrade.

“Daughters are a curse,” a mother hissed at me, enraged at the return home of a daughter whom she believed had been successfully married off.

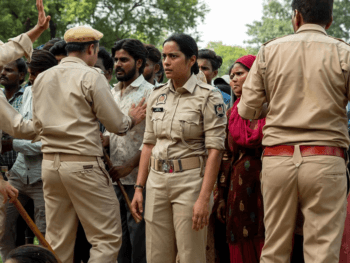

I first encountered the dark side of “son preference” that has long characterised South Asian societies as a young researcher carrying out field work in the village of Amarpur, Bangladesh, in 1979.

One woman, Ruma*, told me that baby girls in her village often died when they fell ill because no one in the family, including their mothers, thought it was worthwhile to seek medical help. Another woman quietly said that some mothers had smothered their infant girls.

As an only child, I had not directly experienced son preference, but I was always struck by the fact that my grandmother, when asked how many children she had, would always answer: “I have six precious diamonds,” by which she meant her six sons. That she also had three daughters was not mentioned. It was only in the course of doing research on the causes of Bangladesh’s extremely high fertility rates in the late 1970s that I came to understand the causes and tragic consequences of son preference.

South Asia is one of the main contributors to what has been dubbed the phenomenon of ‘missing women.’ Millions of women are ‘missing’ because they die in much larger numbers than men at almost every age. They die from malnourishment, lack of medical care, and infanticide. Some of them have never been born, rooted out through prenatal sex selection. This means that the population of Bangladesh, along with that of India and Pakistan, has a lower proportion of females to males than elsewhere in the world, with the exception of the eastern parts of Asia, China in particular.

SONS: AN INSURANCE POLICY?

Most women who took part in my 1979 survey expressed a strong desire for sons. The reasons were not difficult to understand: Cultural traditions restricted a woman’s ability to move freely outside the home, and gave men the responsibility of providing for the family. As a result, men were given privileged access to property and jobs. Women, on the other hand, were dependent on male members of their families – first their fathers, then husbands, and finally, sons – provided, of course, they were fortunate enough to have sons.

Daughters were regarded as an economic liability, to be married off as soon as possible so that the costs of feeding them could be shifted to husbands. The rise of dowry, a relatively new phenomenon in Bangladesh, made matters worse. Sons, on the other hand, were considered insurance against poverty in old age. Having large families ensured that at least some of the sons would defy child mortality rates to look after their aged parents. One obvious way to counter the costs of having many children was to let less-valued female children die – usually through malign neglect.

Since my early field work, the spread of contraceptives and the desire to educate children have contributed to declining fertility rates across South Asia. Unfortunately, in India this has been accompanied by increased discrimination against daughters. While parents might opt to have fewer children, sex-selective abortion is being used to ensure that these children are solely or predominantly male. The result is an abnormally high ratio of boys to girls at birth.

Puzzlingly, the same thing does not seem to be happening in Bangladesh. On the contrary, national statistics seem to suggest that the “missing women” phenomenon is declining. Survival rates of baby girls are increasingly on par with that of baby boys and there is no evidence that parents are resorting to sex-selective technologies.

So, nearly 30 years after my initial field work, I returned to Amarpur in 2008 with a team of colleagues to find out whether Bangladesh’s daughters were indeed surviving infancy, and if so, why.

THE RISE OF THE DAUGHTER IN-LAW

Using similar research methods as in 1979, we found a marked shift away from son preference towards greater indifference to the sex of the child. Most women we interviewed wanted fewer children and no longer cared much if they were boys or girls. Indeed, some expressed a preference for daughters.

Detailed interviews with village women helped to flesh out some of the reasons for this shift in attitudes. One became almost immediately apparent. We dubbed it “the rise of the daughter-in-law.”

Mariam, one of women we interviewed, explained, “The value of women is higher than that of men these days. Women look down on men. They think that now they can earn money and have an education. If the husband does not earn much of an income, the woman can afford to say, ‘I don’t need a husband like you.’’’

Evidence suggests that women are indeed more educated than before and are earning incomes on a scale that would have been unthinkable when I first undertook my field work. Microloans for women, the increased hiring of women by the expanding NGO sector, the rise of an export-oriented garment industry, and even the Green Revolution in agriculture have all generated demand for women’s work. Young women now enter marriage on far less dependent terms than before and are less willing to put up with abusive husbands and in-laws.

Film and television have been major forces behind the rise of the daughter-in-law phenomenon. In a society that shuttered women at home, the spread of satellite TV opened a window to different worlds: News, talk shows, soap operas, and ubiquitous Bollywood offerings have helped women gain new understanding of their rights. They now know what to do if they are abused, beaten, or divorced. Their ideas about love, sex, and romance have also been influenced. Wives have now aware that they have power over husbands that can offset a mother-in-law’s hold. And with families becoming increasingly nuclear, husbands and wives focus more on ensuring the future of their own children than on their obligations to the husband’s extended family.

DAUGHTERS: PRECIOUS DIAMONDS?

The rise of the daughter-in-law is only half the story. If parents can no longer rely on their sons and daughters-in-law to look after them in their old age, they now turn to their daughters. Daughters are deemed more loving, more compassionate than sons. And the strides they have made in education and employment means they have become an insurance policy for old-age security.

Mothers have been central to this process. In Amarpur, mothers spoke about their aspirations for their daughters, describing how they had suffered during their own marriages. They were determined to provide their daughters with better opportunities. As Buli, one of the women, told us, “Girls used to be married off very young and they would bear a lot of hardship and abuse at their in-laws’ house. But now girls are going to school. If she passes intermediate levels of education, there is a chance that a girl can get a job and feed herself. She will not have to depend on someone else’s son like we had to. She will be able to fend for herself. That is why I want to educate my daughter, so she can stand on her own two feet.”

So, paradoxically, the very independence that older women decry in their daughters-in-law, they have inculcated in their own daughters!

Daughters, in turn, value the sacrifices their mothers have made to educate them as they now have the economic capacity to support their aging parents, as well as the independence of spirit to persuade their husbands to let them provide this support. And should the marriage break down, they can return to their parents’ home, knowing that they will not be regarded as an enduring curse.

As Morgina told us, “If I had one child, I would want a daughter. I think daughters are better; they are pulled by feelings for their mothers. They want to know whether you have eaten, how you are doing, what you are doing. They can keep a look-out for you even after marriage if they want to.”

Daughters, just as their brothers, have become “precious diamonds.”

Naila Kabeer is Professor of Development Studies at the School of Oriental and African Studies, London University. Kabeer’s research on the ‘missing women’ of Bangladesh was carried out in collaboration with the Centre for Women and Social Transformation at the BRAC Development Institute and supported by Canada’s International Development Research Centre (IDRC).

BY NAILA KABEER / PUBLISHED IN THE FASHION & STYLE ISSUE, OCTOBER 2012