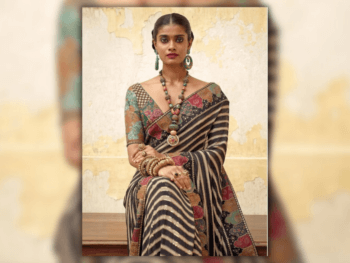

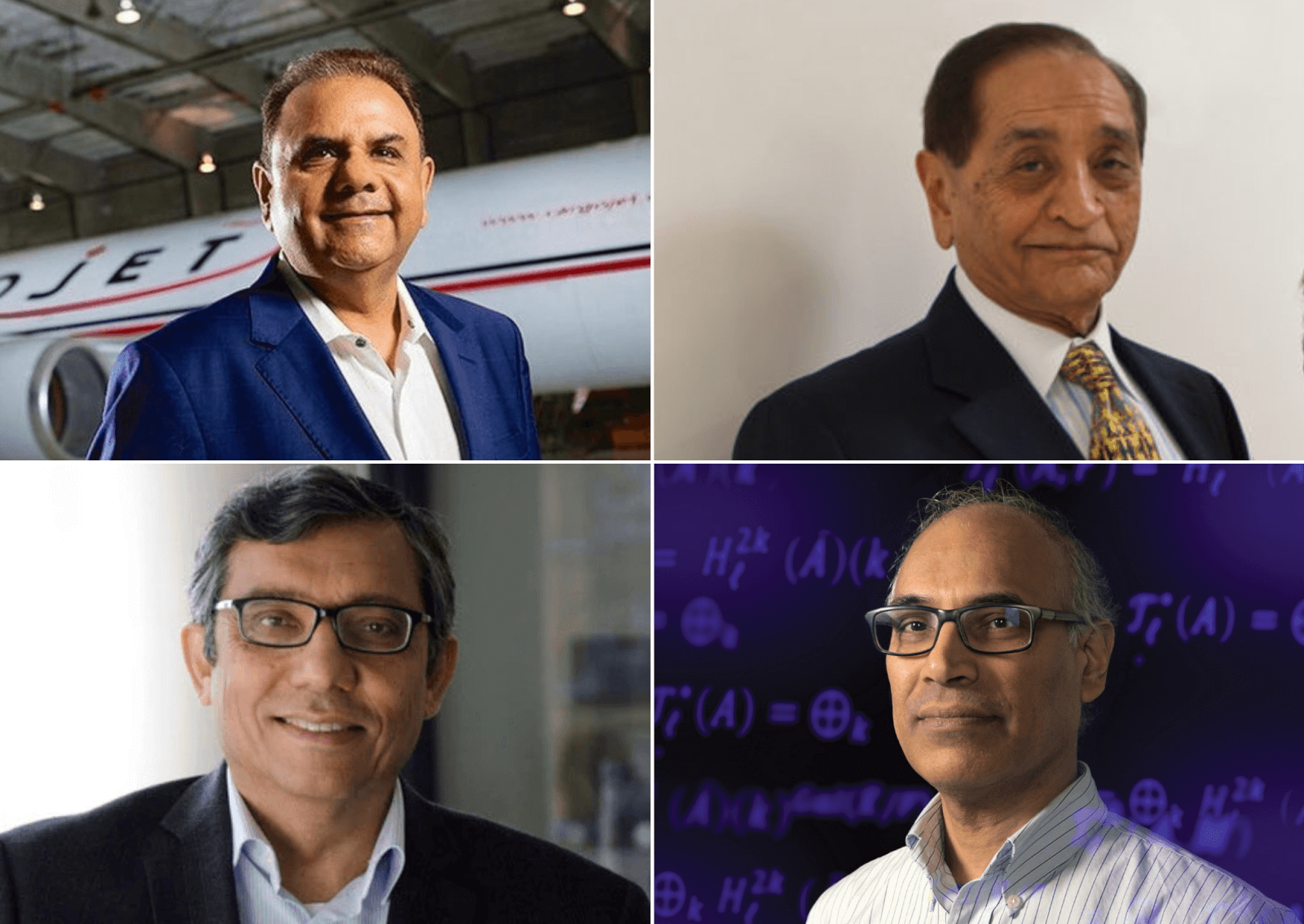

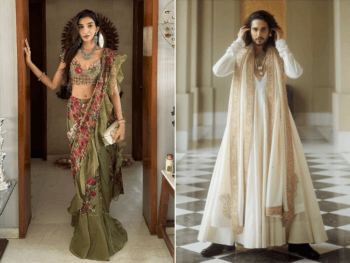

A peek into the lives of the Indian artisans who work to dress the rich.

A recent meeting with the artisans at Jharcraft, Jharkhand Silk Textile and Handicraft Development Corporation Ltd., was a heartening experience. They sat happily in an air-conditioned room embroidering kurtis and dupattas in kantha work. “It is a pleasure to spend our day here at the sampling unit and return home with a decent salary every month,” Chandravati Devi told me. “Apart from the salary, there is provident fund (similar to a pension plan), free medical facilities, and also an option of taking bank loans,” she added. “An artisan at Jharcraft gets the same employee benefits as a designer,” said Shahidullah Mulla, who works as a tailor at the company. “But what I love most about my job is that I’m working for an organization that truly thinks about its staff at all levels.”

One only wishes that every artisan in India could be as happy and contented as this group. Their fate could be different if every stakeholder in the fashion and textile industry thought as much about the labourer who weaves, dyes, prints and embroiders apparel or puts together accessories for the upwardly mobile section of the society.

But all’s not well

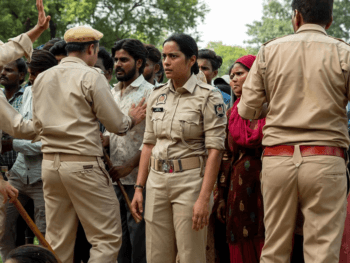

In a country like India, where population is a deterrent in every effort for improvement, it is not difficult to imagine why the artisans are still not living a comfortable life. The garment industry in Tirupur, Tamilnadu, India, employs girls 14 to 18 years old. Hailing from an economically weaker section of the society, these girls are lured by labour agents/middlemen who get them from their villages with a promise of a daily wage of Rs. 195/day (or about $4 CDN), a bonus of Rs. 30,000 to 50,000 (approximately $600 to $1,000 CDN) every three years and good accommodation and food. “In reality, these girls are paid not even half of that, are served only rice for their meals, and bonuses are mostly unheard of,” says Ramesh Raju, a labour activist. Face masks and caps which are essential for a worker’s safety are missing from the scene. These innocent young women often die due to lack of know-how about the use of machinery. Some go missing when sexually assaulted.

Another set of easy exploits is kids 10 to 14 years old. Owners of deft nimble fingers, they are considered safe bets for handling delicate work such as fixing small decorative stones in jewellery, making bangles and fine embroidery, especially zari work.

It can cost them their health

Some of the sweatshops and factories that these labourers work in are neither well lit nor properly ventilated. Respiratory ailments are common among their lot. Long hours spent standing cause spinal problems. Workers at the dyeing unit are not supplied with gloves; their hands remain coloured all day, and the water-based dyes often cause dermatitis. “Hard skin acquired due to dermatitis easily cracks and allows the dyes to be absorbed, which may lead to cancer,” confirms Dr. Sachin Dhawan, a leading dermatologist from India.

Some of the sweatshops and factories that these labourers work in are neither well lit nor properly ventilated. Respiratory ailments are common among their lot. Long hours spent standing cause spinal problems. Workers at the dyeing unit are not supplied with gloves; their hands remain coloured all day, and the water-based dyes often cause dermatitis. “Hard skin acquired due to dermatitis easily cracks and allows the dyes to be absorbed, which may lead to cancer,” confirms Dr. Sachin Dhawan, a leading dermatologist from India.

Parveen Sikkandar, director at Damini The Artisans Of India, a fashion business with ethics, adds a word about the kids who work with accessories: “After custom creating fancy earrings for a customer, my fingers ache for a couple of hours, so one can imagine the plight of the kids who do this on a regular basis.”

Why are promises not kept?

There are adequate legal provisions for protection of child and labour rights in India. With laws like the Child Labour Act and the Juvenile Justice of Children Act of 2000, both of which ban hazardous employment for a child younger than 14, there is no reason why children should work. The Forced and Bonded Labour Act and The Health and Safety in the Workplace Act look after the rights of adult labourers. Plus, each state has a minimum daily wage for unskilled/semi-skilled/skilled labourers falling within a range of Rs. 100 to 350 (approximately $2 to $7 CDN).

But a major issue is lack of enforcement of these laws. There is illiteracy and lack of awareness among the poor labourers and the middlemen take advantage of that. The workers’ singleminded dedication toward making a good living leaves them even more vulnerable to the treatment that they get. They are willing to work for a pittance, put in extra hours without compensation and wait for long periods to get paid at all.

A change is possible

We need to work together to move things in the right direction. The fashion designer who usually works with a small set of karigars who are paid a high wage of Rs 350 to 450 (approximately $7 to $9 CDN) per day will have to look beyond her domain. She’ll need to ensure that every worker who works for her brand at any level, whether weaving, dyeing, embroidering or the painting unit, is paid his due and is an adult.

“An amendment in the existing Child Labour Law with a blanket ban on child labour and a strict enforcement of Right to Education can improve things,” says Bhuwan Ribhu, an activist at Bachpan Bachao Andolan, an NGO working for child rights. The good news is that the Labour Ministry has already proposed this and is waiting for a nod from the government. “Rehabilitation of labourers should include social security so that they do not get back to their old, underpaid work,” he adds. Parveen seconds him. “If only we stopped being so obsessed with handwork and accepted machine work instead, so many kids could go to school.”

Consumers should check with a brand every time they purchase their goods to ensure their karigars were all adults and paid well for their work. It just might make the brands more conscious about their duty. A government policy to check this and label ethical brands would shake things up even more.

People who work at the grassroots level for the poor, train them and create employment for them, are needed today. Most selfhelp groups have been quite successful in their efforts. Rekha Mann, who works with the Phulkari Cluster Head in Rajpura, Punjab, has been pivotal in creating employment for more than 1,000 women. She has trained them for skill up-gradation, machinery usage and has even marketed their talent. Each of her employees today works either full-time or are freelances and get a monthly wage, life insurance and access to a medical practitioner. Her reward? “My joy knows no bounds when ladies who were once a part of our organization call up to invite me to their exhibitions in Singapore and Italy.”

BY: PRITI SALIAN / PUBLISHED IN THE FASHION & STYLE ISSUE, OCTOBER 2012

PHOTOGRAPHY BY PARVEEN SIKKANDER, REKHA MANN