Skin Whitening Is An Increasingly Lucrative Industry In Countries Like India And It's Showing No Sign Of Slowing Down

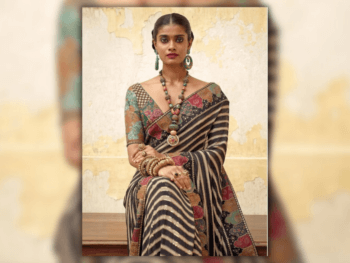

The bronzed, dusky skin that's so sought after and attained with tanning products and tanning salons in Europe and North America would probably seem like a strange practice in Asia, where alabaster skin is the preferred aesthetic. In India, for example, skin-whitening products are a multi-million dollar industry with companies like Hindustan Unilever Limited and Emami making a massive profit each year. Hindustan Lever Limited's Fair & Lovely skin-whitening cream is the largest selling product of its kind in the world, marketed in 40 countries in Asia, Africa and the Middle East. In India, it dominates over 80 per cent of the skin-whitening cream market and is consumed by an estimated 60 million people throughout the Indian subcontinent.

For all its popularity and near monopoly of the skin-whitening cream market, Fair & Lovely has met been with equal chastisement from the public. The print and television ads by Fair & Lovely have been scrutinized the most. Most of them correlate fair skin with success and happiness, whether it is in one's personal life (finding a husband) or one's professional life (getting a good job). While the company and its proponents argue that the cream is about "choice and economic empowerment for women," its critics believe it creates unrealistic and unfair standards for women. The carefully marketed rhetoric seems to suggest that darker women suffer from a condition and that skin-whitening products offer a cure.

But this type of insidious advertising isn't limited to Fair & Lovely, with several companies offering similar remedies in their skin care lines. Critics argue that for all their talk of empowerment, they do more harm than good. Skin-whitening products have been accused of promoting a false ideal of beauty, perpetuating racism and masking potential health risks. Others detractors, such as Professor Amina Mire of Carleton University, point out the way in which these products are also the result of colonial residue. In Africa, the often clandestine practice is the result of an inferiority complex from years of white colonial oppression.

In India, the desire for fair skin goes beyond the impact of the British Raj and aspirations towards a Westernized ideal of beauty. After all, the Mughals also had light skin. The desire for fair skin has a much more complex cultural history that also has to do with class. For centuries, light skin has been a marker of wealth, distinguishing the rich who had the luxury of staying indoors and not work from the poor who worked outdoors under the sun. But the issue is as complex as India's social organization and ideas about light skin are also entrenched within the country's caste system.

It's no surprise then that the poor are also targeted by companies. Unilever admits that the company generates half its business from rural areas. Its products are sold in around 500,000 villages, thanks to Project Shakti, which invites women from villages to become "direct-to-consumer sales distributors." They sell soaps, shampoos and skin-whitening creams to other village women and they in turn earn an income from the money their sales generate.

But Dr. Aneel Karnani, an associate professor at the University of Michigan's Stephen M. Ross School of Business, doesn't buy Unilever's corporate responsibility shtick. If you've followed the debate surrounding skin-whitening cream, you may have already heard of him. Dr. Karnani is particularly vocal about Unilever and its unsavoury marketing tactics. The statement on Unilever's Shakti Project reads: "Unilever believes that one of the best and most sustainable ways it can help to address global social and environmental concerns is through the very business of doing business in a socially aware and responsible manner." They might believe they're empowering them, but Dr. Karnani does not. "The way to empower a woman is not to sell her Fair & Lovely," he explains. "The way to empower a woman is to give her a job so that she's earning independence. And then she can decide whether she wants to buy these products or not."

The rhetoric of empowerment has further been destabilized by various women's organizations in India who have lobbied against these products. In the case of Fair & Lovely, the Indian government banned two ads in 2003 after a yearlong campaign by the All India Democratic Women's Congress. Another organization, Women of Worth (WOW) created the "Dark is Beautiful" campaign last year to combat the stigma attached to dark skin and celebrate the diversity of Indian women.

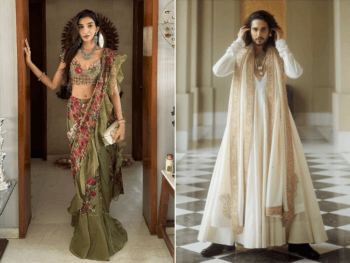

The controversy surrounding skin-whitening products may not be new, but recently, it's received more attention than usual. For one thing, companies have zoned in on a previously untapped demographic-men. The ads use a similar angle to proposition males: Light skin will lead to an improved love life and job prospects. In India, Emami Fair & Handsome is the most popular brand for men. The product's success owes in no small part to Bollywood actor, Shahrukh Khan, who is the face of the popular product. He's won over consumers with his natural charm and wholesome good looks, but he has also received a fair amount of criticism for his endorsement of such a controversial product.

Also making headlines is GloRiel, a skin-lightening cream that's being developed by two graduate students at Carleton University. Pratik Lodha and Eman Ahmed-Muhsin are the brains behind GloRiel, which is based on Nobel Prize-winning gene-silencing technology. If patented and sold to a cosmetic giant, it will bolster what is already an exceptionally lucrative market.

When Canada's CBC.ca broke the story, it generated an interesting debate. One poster, presumably Pratik (as he identified himself on the website), defended the technology. Among his arguments was that the technology "has broad potential applications in skin care including treatment of age spots, skin blemishes, and other cosmetic needs" that go beyond skin lightening. Multinationals and the creators of GloRiel may defend their right to make these products available in the market, but they certainly aren't the only perpetrators. Bollywood has also contributed to presenting a very specific ideal of beauty, with actresses like Aishwariya Rai, whose beauty is exemplified by her fair skin and light-coloured eyes.

"There is an increasing Westernness in the beauty style of Bollywood today," says Tayaba Jafri, Global Makeup Artist for Laura Mercier Cosmetics. "Contact lenses and all. However, the interesting part is that although the heroine is always the fairest girl amongst the dance troupes, over the decades some of the iconic Bollywood heroines weren't overly fair. Rekha would be a prime example. In fact, some of the great finds of Raj Kapoor himself, that were touted as beauties with milky white skin, such as Mandakini (she even had natural blue eyes) and Zeba Bakhtiar, flopped and weren't very accepted by audiences."

Apart from savvy PR by film companies, Bollywood stars have readily offered their services to promoting such products. Olay Natural White, a whitening cream by Olay, enlisted the help of actress Katrina Kaif to endorse their product. L'Oréal-owned Garnier launched its first range of skin-lightening products for men with the help of John Abraham. Consciously or unconsciously, actors and actresses are helping sell a lifestyle that presumably can only be attained with fairer skin.

Likewise, the Miss India pageant also reinforces the correlation between beauty and fair skin. According to Susan Dewey, author of Making Miss India Miss World: Constructing gender, power and the nation in the World, all the women in the 2003 pageant were taking some sort of medication to "alter their skin, particularly in [colour]."

The belief in fair-skinned beauty isn't as pervasive in the European and North American diasporas and as a result, the market also isn't as strong for skin-whitening products. But products like Pond's whitening cream, Emami Fair & Handsome and Stillman's Bleach Cream are still readily found in South Asian grocery stores, right alongside other similar imported products from India and Pakistan. The only difference is that they don't fly off the shelves. "North American or Western countries are not so lenient with drug laws and many bleaching ingredients are basically outlawed or would never get approval, but the fact that you do still see pseudo-bleaching products shows a need/desire in the market," says Jafri.

Taken out of its cultural context, the use of skin-whitening products might seem like a strange practice to people living in North America. But the popularity and pervasiveness of such products is the result of multiple factors working simultaneously to create a demand. In addition to creating awareness of such a phenomenon, it may also be worthwhile to examine why these perceptions of beauty persist and how they can be changed. So far, the controversy surrounding skin-whitening products has been about culpability, which hasn't generated dialogue so much as it has resulted in a stalemate amongst its foes and advocates.

BY: MISHAL CAZMI / PUBLISHED: MARCH/APRIL 2010 ISSUE

(PHOTO COURTESY OF ISTOCKPHOTO.COM)