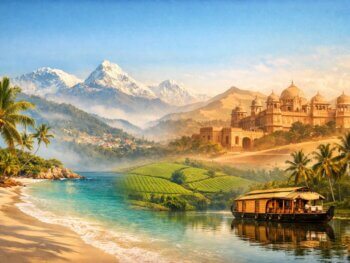

Nagarhole National Park

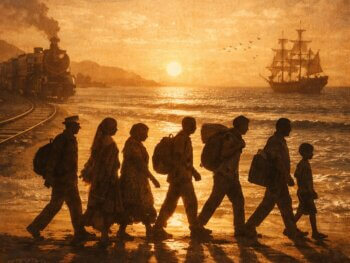

We have an appointment with a tiger. I hope. There are seven of us in the safari jeep–a guide, a driver and five eager tourists: a camera-toting engineer from Bangalore, a Swiss couple and two Canadians (my sister and I). As we leave the main gates separating our temporary home, the Kabini River Lodge, from its surroundings at the Nagarhole National Park, our guide assures us we’ve come at the right time and regales us with tales of recent sightings.

The jeep is open to the elements, with only a thick tarp overhead to protect us from the sun. Though this early in the morning, the sun is still only a faint presence, providing just enough light to spotlight trees and break up the last of the dawn fog.

Just a few minutes into the forest, we surprise a herd of chital or spotted deer. They are at the side of the dirt road, in a semi-cleared area dotted by slender rosewood and teak trees. The little ones bound into the safety of the forest proper and vanish into the tall grasses, while some of the bolder males stare at us as we pass by.

Our driver barely slows down, there are thousands of deer in the forest and spotted deer, the most common species, are hardly worth noting. Now, if we’d sighted one of the rarer species, like a sambar, four-horned antelope or barking deer, then that would be worth a stop.

At the moment, we are headed to a large watering hole, known to attract wild elephants and the jungle predators–leopards, jackals and of course, tigers.

The park is crisscrossed with water, whether it is tiny streams or the four major rivers incuding the Kabini, Lakshmana, Teentha and Nagarhole. In fact, the name Nagarhole, pronounced as Nagarholay, comes from the Kannada “naga” or snake and “hole” or streams. And although the park was officially renamed in honour of late prime minister Rajiv Gandhi, it is still most commonly known by its older name.

The park is crisscrossed with water, whether it is tiny streams or the four major rivers incuding the Kabini, Lakshmana, Teentha and Nagarhole. In fact, the name Nagarhole, pronounced as Nagarholay, comes from the Kannada “naga” or snake and “hole” or streams. And although the park was officially renamed in honour of late prime minister Rajiv Gandhi, it is still most commonly known by its older name.

When we reach the watering hole, we meet a family of wild boar. They are happily living up to stereotypes, wallowing in the muddy banks and they ignore us. We settle in to wait for the main attraction.

Our engineer turns out be an avid birdwatcher and pulls out professional-grade binoculars that he obligingly shares with the rest of us as he and our guide point out the dozens of bird species. The region boasts over 250 bird species ranging from common herons and kingfishers to the endangered Malabar Trogon, the malabar trogon, the malabar pied hornbill and the crested hawk eagle.

“Tusker,” interrupts our driver and all heads follow his outstretched arm to the opposite shore. There is a male elephant, his ivory tusks gleaming against his large grey body. We all watch spellbound as he casually munches on a strand of bamboo. As if his presence is a signal, we start spotting other wildlife.

“Gaur,” points out our guide motioning to the left of the elephant, where a white-socked brown buffalo heads towards the water to drink. “Crocodile,” at the water’s edge by the Swiss husband. “Crested serpent-eagle,” murmurs the bird-watching engineer. “Sambar,” contributes my sister.

But alas no tiger.

Nearly an hour later, we give up and head back into the forest for our drive back to the lodge. On the way back, we nearly run into a sloth bear. I see nothing but a black blur that vanishes into the forest, but it causes major excitement amongst the rest of our party. According to our guide, sloth bears are quite rare.

Back at the lodge, we sit down for a hearty breakfast and commiserate with our fellow guests over eggs and South Indian idlis. There are currently thirty of us and we’d gone out in a half-dozen different jeeps for our morning safari, but nobody had spotted a tiger today. The patriarch of a Delhi family shares a video of wild dogs taken the previous evening.

I spend the late morning on a hammock pretending to read a book but really watching a family of monkeys play in a treehouse. Nearby, a resident flock of sheep mow the lawn, while children–human children to be clear–swing from tires suspended from the massive branches of an age-old tree.

I tell myself I’m secretly glad not to have seen a tiger as yet. This was only the first of five jeep safaris I have planned for the next few days, and I want to save the best for last.

My more active sister goes on a walk around the compound and comes back with stories of baby trees, planted by celebrity guests such as Goldie Hawn.

The Kabini River Lodge has hosted visitors for well over a century. The oldest buildings at the lodge are colonial in style and date back to the days when this was a favourite hunting camp for the Maharaja of Mysore. It is a gracious wilderness retreat, an ideal place to relax away from the bustle of modern Indian life, free of cellphones (banned), radios and television.

To put you out of your suspense: I end my trip as the only person who doesn’t see one. I see a leopard, mongoose and giant flying squirrels but am cursed by bad tiger luck. But I can’t find it within me to complain; I just have a compelling reason to return.

WORDS/PHOTOS RITIKA NANDKEOLYAR

COMMENTS

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE

Newsletter Sign Up

Subscribe to our FREE newsletter for all of the latest news, articles, and videos delivered directly to your inbox each day!