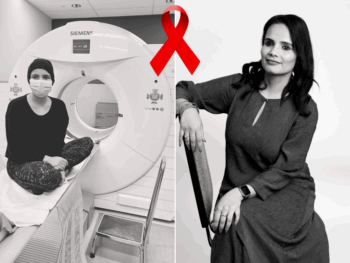

When Dr. Sheela Basrur came to be a guest on a TV program that I produce, I was very excited. She showed up in a well tailored suit looking gracious and classy, betraying any evidence of her recent battle with her illness. Her build was delicate and slight like a tiny bird. I was expecting a more serious, self-contained, distant persona given her many accomplishments. A circumstance that I am all too familiar with in my chosen industry riddled with massive egos and self-important prima donnas who are always ready to display all that they are with their dismissive attitude. She was far from this. She smiled sincerely and greeted me with a warm hug. With her sister and close friend alongside for support, she was eager and pleased to do the interview.

Dr. Basrur has cancer–a rare form–a tumour that affects blood vessels and soft tissue. Known as Hemangiopericytoma, it comprises only one per cent of all cancers. In her own words, she requires many months of further investigation and treatment.

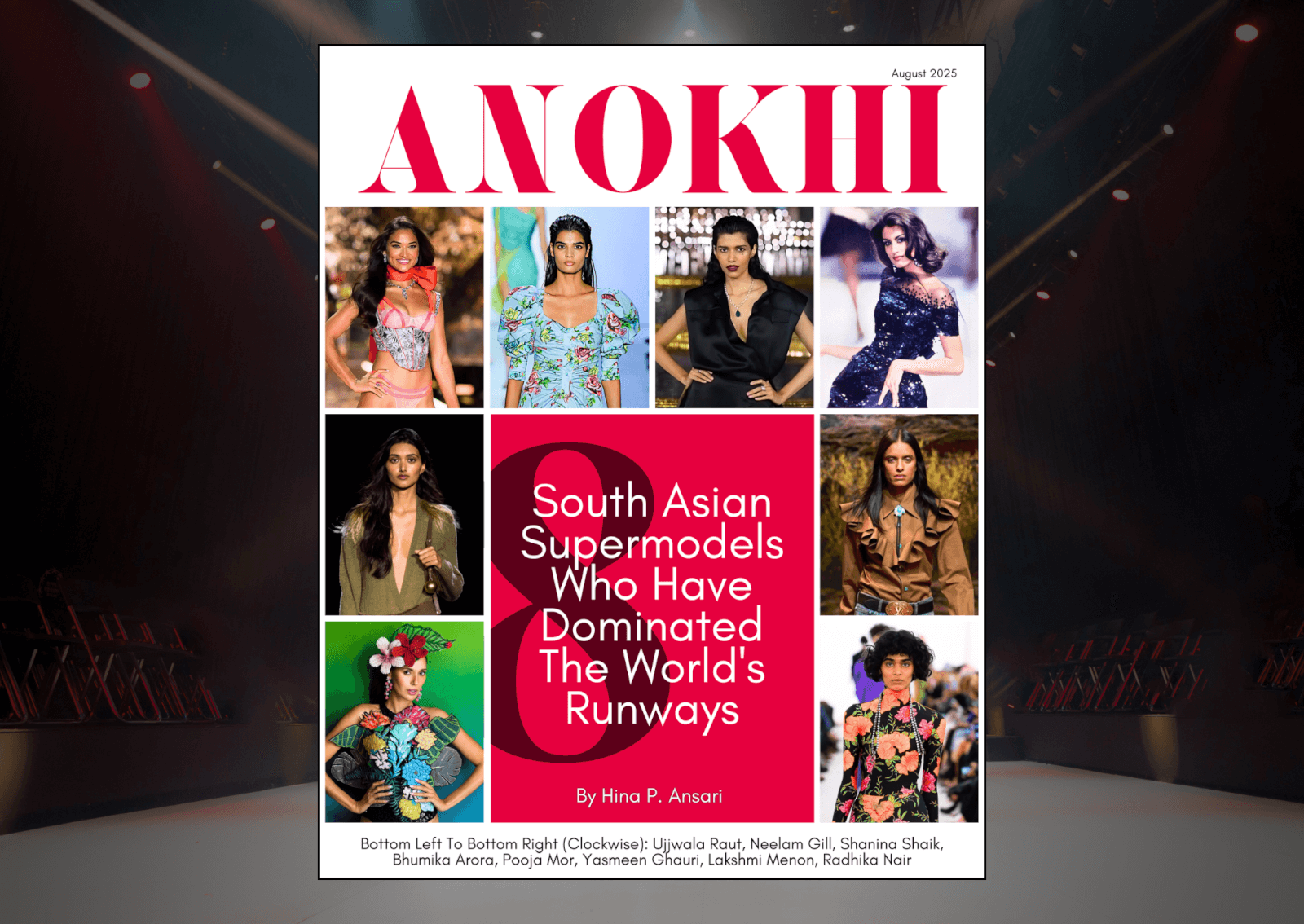

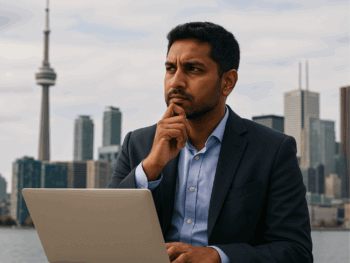

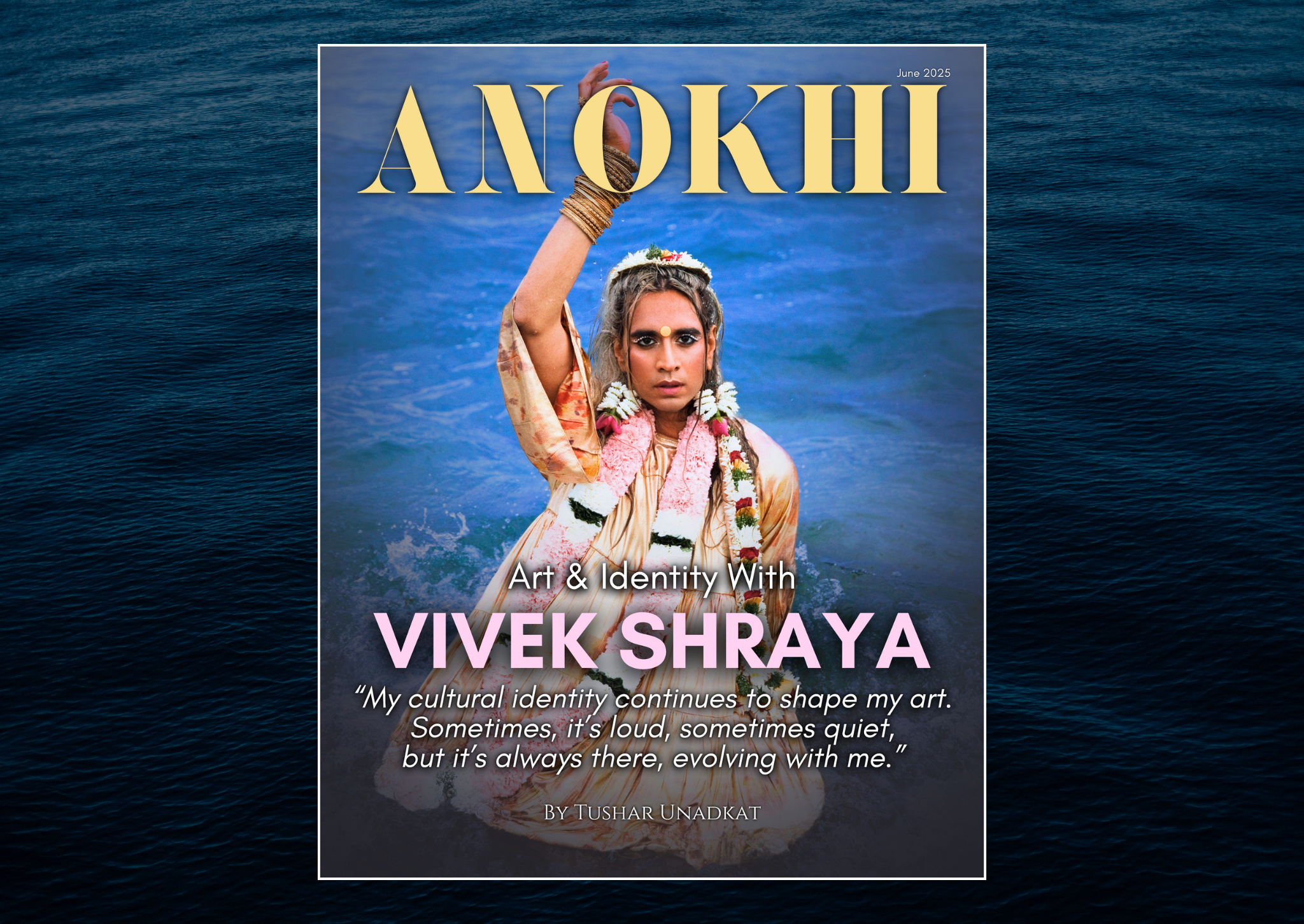

She first caught my eye on TV during the spring of the 2003 SARS crisis. This well-poised South Asian woman speaking so clearly, deliberately and penetratingly from behind the cluster of press conference microphones. She intrigued me. ‘She must be tough,’ I thought ‘to get to where she is today.’ She is a doctor and a public health spokesperson. In the present day work place–a landscape so sorely lacking of real life mentors for younger South Asian women in many a field still dominated by white men –we need more women like her, I thought.

Fast forward to the day I met her at OMNI television studios; still poised, articulate and undeniably intelligent, I had a chance to tell her she was that mentor that younger women needed to know more about in this dearth of professional advisors from our cultural background. She quickly agreed to a magazine interview. She cordially invited me for tea and a chat at her sister’s suburban home in Scarborough where she was presently residing. “Come by the house,” she said.

I arrive at the house on a warm spring evening after work in May. Her sister Jyothi tells me as I sit down that Sheela hasn’t been feeling well all week, but she really wants to do this interview. “This is the kind of stuff that makes her feel good right now,” her sister tells me quietly. I don’t want to impose on her time or her delicate health. But I am told its fine, and she absolutely did not want to reschedule.

Leaning on the piano is a large bright poster made of construction paper with pasted-on family photos. Colourfully penned in felt markers are the words “Auntie Sheela We Love You.” Clearly a ‘cheer-up’ present made from a child’s love. Sheela and I sit down for our chat.

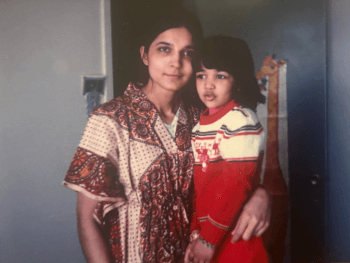

Her parents came to Canada in the 1950s as single graduate students both studying genetics. They met here, married and Sheela was born in Toronto. Sheela remembers growing up in charming Guelph with her parents and her younger sister Jyothi, and being one of the first visible minority families in town. She had a happy childhood. Her most carefree memory is of wiling away the summer days bicycling through a wonderful field. “It was a small town, very safe. I was blessed and fortunate,” she recalls.

She recalls those moments in childhood that shaped her. She remembers making a friend in the sand box. “We stayed friends for 50 years.” And when that friend passed away years later at the end of 2005, it caused Sheela to look at her own life in a different way. “I realized I was working too hard. There wasn’t enough time to enjoy anything.” Her dear childhood friend had put a lot of energy into working hard all her life so that she could have a better future for herself but as Sheela puts it she, “never had a chance to enjoy that future. It made me realize you need to enjoy your present day as much as you can.”

Sheela’s mom put her dad through medical school. As a child, Sheela remembers her mother, now a professor emeritus at the University of Guelph who worked for 40 years at the Ontario Veterinary College, as being the first powerful role model she knew. Her mom came from a matriarchal society–from Kerala–and her father from Banglore. Both South Indian: a people known for their strong commitment to scholastic achievement. Sheela remembers, “I grew up in an atmosphere that was a very high achieving environment.” She marvels out loud at her father today, still a doctor working full-time as a radio-oncologist who, “even though he is 76-years-old now, he is still saving lives.” She ponders, “He is amazing. He could be fishing in Florida right now.”

From a young age she felt you worked hard for anything that mattered. “I wasn’t a brilliant wave,” she says of herself. She knew in order not to disappoint her parents she had a sense of personal responsibility to work hard and set high goals for herself. “Parents make you or break you,” she says, “If your parents can be there for you, you are so much farther ahead. You exceed. Children don’t set high goals for themselves. Others do it for them. You learn from hard work getting you somewhere.”

She was clued in at an early age on how to command respect from her cohorts (an ability that many young women only come to reflect on in their mid-twenties). “I have always felt, since I was a child, voice is how you are presented to the world.” She knew at the time that one had to work on using vocal presence to command authority and respect. She calls it her “entry card.” How prophetic for the young achiever to deliberately adopt this professional tactic. One cannot help but be reminded of her calm, clear voice that was so reassuring to Canada’s largest city in a time of uncertainty and fear; years later the accolades would read how she provided a “voice of reason, providing calm, clear and accessible information to a nervous population.”

After completing an undergraduate science degree at the University of Western Ontario she became a doctor of medicine in 1982 at the University of Toronto and later completed her masters. In the mid 1980s, while in her late twenties, after already working for a year in general practice, she informally studied the Hindu religion when she trekked around the Himalayas. For one year she explored India, Nepal and South East Asia. In this year of self-exploration she found her inspiration to pursue the study of public health.

Many first met Sheela during the 2003 SARS crisis as the medical officer of health for the City of Toronto, which she was appointed to in 1998. In this job she headed one of the largest public health bodies in North America with an annual operating budget of $160 million and 1,800 staff across 30 locations.

Her work during that difficult time did not go unnoticed. In 2004 Sheela was appointed Ontario’s chief medical officer of health and the assistant deputy minister of public health. Nearly halfway into her five-year term she began suffering chronic back pain and she had to be rushed to emergency for surgery. She stepped down for sick leave from the position on December 6, 2006.

At 50-years-old, dealing with her illness now, she reflects, “From a spiritual perspective I have reached my peace with my god.” And she is hopeful and courageous in her fight, although, ever the true health care professional, she speaks calmly and succinctly of her own prognosis, “I am hanging in there. I’ve had a moderately rocky course.” She started chemotherapy in March to cut off the tumour’s ability to create its own blood supply and then started a new treatment in May and she reports, “It appears to be working now.” Sheela’s chemotherapy will continue until autumn of 2007. “I’ll see what the future brings when it comes and whatever it brings I am determined to love what I have,” she tells me.

I ask her what she would tell her 22-year-old self today if she could. After some reflection she says she would tell a young Dr. Basrur to, “get as much practical experience as you can,” but also would tell her, “Life is to be enjoyed as long as it can be.” She goes on to say, “People have to find a balance within themselves. All those issues come down to whether you feel balanced as a woman.”

Making commitments to informed choices is also a key to success, Sheela believes. “I would consult and look at issues up and down and sideways and stick with it. I had to do that in work and my personal life; to be careful, thoughtful and decisive.” And every profession deals with people dynamics. I ask her about office politics. “You need to cultivate relationships as a tool. You have to understand people’s motivation.”

She provides the age-old advice to follow your dreams and never let culture and family detract from them; a generations-old struggle especially for our cultural group. “Know yourself and your heart,” she advises, “Know your dreams and somehow don’t do anything but follow your dreams,” and even if that means not having the financial security that our parents’ generation coveted so earnestly. “You might have to make ends meet but don’t sacrifice your dreams,” she says, “I have seen so many young people who pursued a life that was imposed upon them and then became happier once they escaped.” Certainly solid advice coming from the doctor with a proud public legacy.

WORDS RIMA KAR

PHOTO NRANA

COMMENTS

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE

Newsletter Sign Up

Subscribe to our FREE newsletter for all of the latest news, articles, and videos delivered directly to your inbox each day!