“Where the language of stone defeats the language of man,” were the words that famed Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore used to describe the Sun temple of Konark. I can well understand why.

First, there’s the scale. I’m just a bit over 5 feet tall so I’m used to feeling short, I accept that – but this temple makes me feel tiny. I’m standing next to a massive stone wheel and my head barely reaches the spoke.

There are twenty-four of these wheels – remarkably well-preserved considering their age – set in pairs around the base of the massive chariot-shaped temple. At its height, the now-collapsed inner sanctum reached 229 feet – about 23 stories!

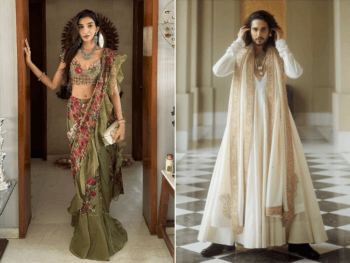

Next, there’s the intricacy of the work. Each inch of the 13th-century temple is carved with complex patterns of fantastical beasts, legendary heroes and sumptuously-dressed deities. Legend has it that over 12,000 sculptors spent twelve years working on this monument to the Hindu sun god Surya.

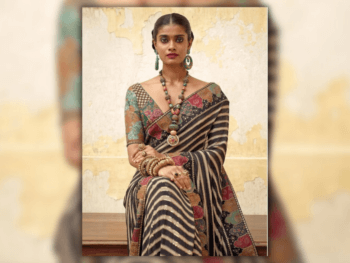

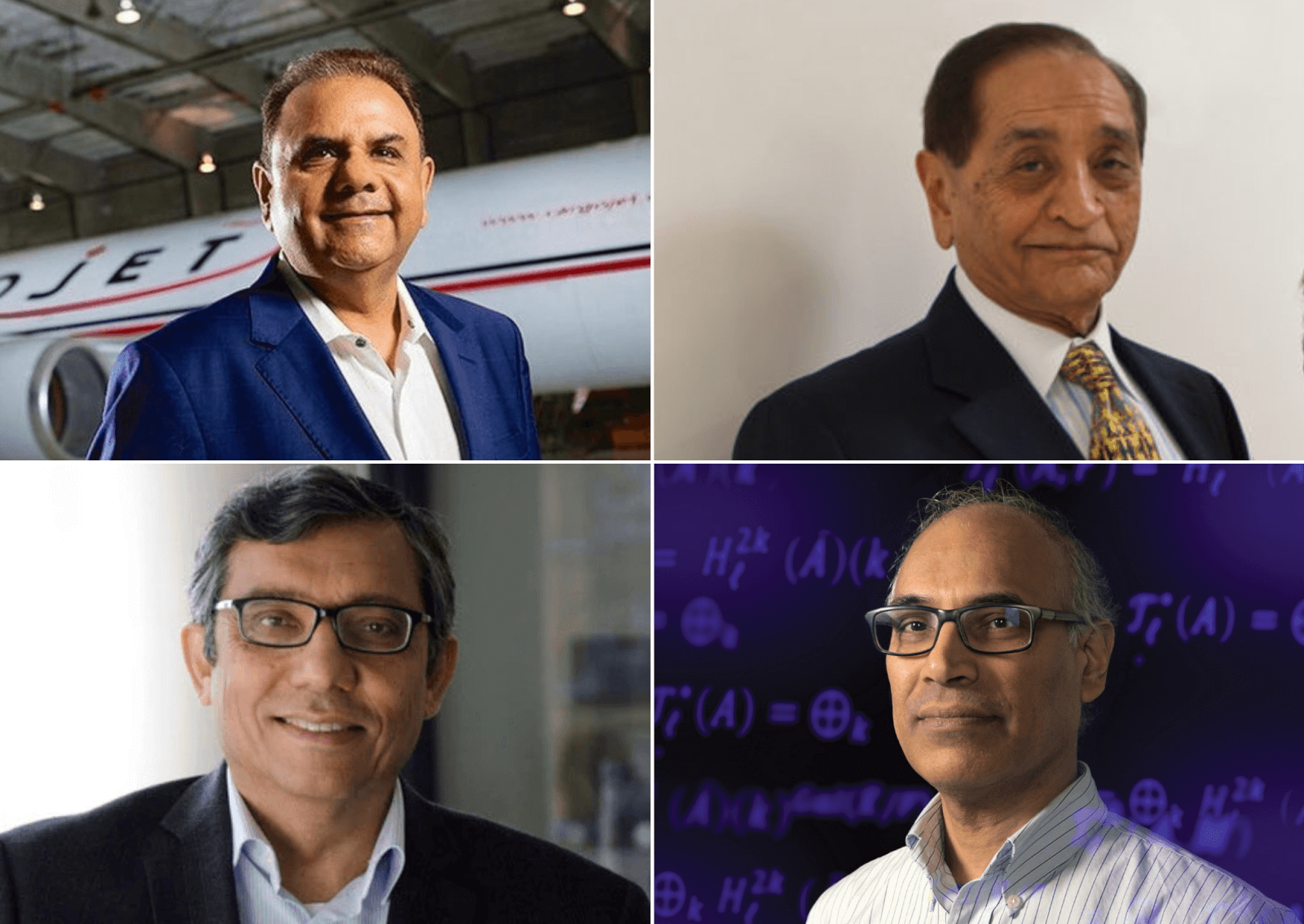

THE GRANDEUR OF THE KONARK SUN TEMPLE IS ELEVATED BY ITS CHARIOT WHEELS

The stones are cleverly fitted together like a puzzle, there’s no cement or mortar holding the individual black granite pieces together – only clever design.

The artisans of Kalinga, the ancient kingdom that once encompassed Konark, had centuries of experience building ever more elaborately decorated temples. Although the sun temple is the only example of their work in current-day Orissa with UNESCO world heritage site status, there are many other temples in this state that are worth visiting.

A few days ago I’d explored Orissa’s capital, Bhubaneshwar, which is officially nicknamed the temple city. There I only had time to visit a few of the many holy sites that are scattered through the small town. My highlights included the 2nd century BC Buddhist cave monasteries on the twin hills of Khandagiri and Udayagiri – which predate the more famous cave temples of Ajanta and Ellora in Maharashtra – and the 11th century Lingaraja temple dedicated to Shiva.

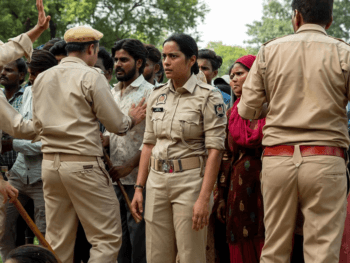

TRADITIONAL CRAFTS OF ORISSA BURSTING WITH COLOUR AND DESIGN

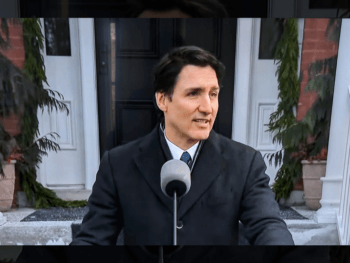

The most visited temple in Orissa however, is the Jagannath temple in Puri. One of Hinduism’s most holy places, the temple hosts millions of worshippers each year. Although the grounds of Jagganath are reserved for Hindus, the balcony of a nearby library doubles as an observation deck which is open to all faiths.

There, anyone can observe the commotion, when each summer, the small coastal town is overwhelmed with pilgrims for its famous Rath Yatra. During the Rath Yatra, the 3 deities, of Jagannath, Balabhadra and Subhadra are paraded through Puri in a grand procession of chariots to mark the start of the gods’ annual vacation.

But winter is the off-season and I am primarily there for the beach, one of the many fine white sandy strips of coastline that are Orissa’s under-appreciated natural treasure.

The beach at Puri actually stretches the entire 30 kilometers to Konark, but as I am feeling a bit lazy I only walk a few kilometers.

It’s a surreal experience. I start near the temple precincts, where constant funeral pyres generate smoke and ashes that are often washed in the ocean, making swimming downstream unadvisable.

Then I pass the main tourist drag. Here wizened old men crack open fresh coconuts with machetes for a quick drink while ice-cream wallahs and pearl-sellers hawk their wares. Here, Bengali families on vacation congregate to build sandcastles or picnic with candy floss and soft drinks. Here, the occasional fishing boat beaches and its crew temporarily takes over the sand to roll-up their 100-foot long nets.

But in less than a kilometer, the bustle fades away. Now, I’ve reached a peaceful tropical paradise, something I’d expect on an exclusive Caribbean island retreat and an unlooked for escape from the madding crowd.

I would experience this solitude again, a few days later in a boat on Chilka Lake. The lake, Asia largest inland brackish lagoon, is home to hundreds of aquatic species. The star attractions are the endangered Irrawaddy dolphins and the million avian residents including one of the world’s largest flamingo breeding colonies.

I have taken a boat out to an observation tower on Nalaban island, one of the dozen of small islands that dot the lake and the heart of the Chilka Lake Bird Sanctuary. It is just after dawn and sun has just begun to burn off the mist that enshrouds everything.

There’s reputedly over 150 different species of birds in Chilka. Several are migrants that spend October to March here before returning to homes as far away as Siberia or Iran. Despite my lack of bird watching expertise and the less than ideal light, in an hour, I spot over a dozen different birds from white-bellied sea eagles to Siberian cranes.

But just like the birds, I’m only a visitor in this eastern paradise. After a few restful days, I return to Bhubaneshwar back to modern India.