Don’t know your copyright from your cappuccino? Not sure what the difference is between a patent and a trademark? Relax. We break down the legalese so you won’t lose it.

Name your favourite business podcast, radio show or television program. At some point you would have heard the phrase “intellectual property” thrown around. If you nodded, smiled and said to yourself, ‘That has to be something to do with patents and music downloading,’ then this article is for you. (In fairness, I nod and smile at most things on business shows – like “short selling” or a “derivatives” – say what?)

In any event, intellectual property refers to a loose collection of intangible rights that cumulatively form some of the most important aspects of a business in today’s information economy. This magazine, your phone and those red-soled shoes you spent $1,000 on — they’re all protected by intellectual property. Copyright, patents and trademarks are probably the types of intellectual property we’re most exposed to. Less commonly encountered types of intellectual property — or “IP” — include confidential information and industrial designs. Let me break it down.

Copyright protects any original literary, dramatic, artistic or musical work. “Original” simply means that it originated from you as the creator. As long as the work is fixed in some sort of tangible medium (paper, canvas, bathroom stall, etc.) then copyright automatically affixes to it. It’s that simple. No formal registration is required. Generally, copyright lasts for the life of the creator, plus — somewhat morbidly — 50 years following his or her death. The copyright holder has the exclusive right to produce or reproduce that work, or a substantial part thereof. Despite this, there are exceptions that permit others to use copyrighted works without permission for things like research, private study, criticism, review and news reporting.

Lastly, there is a quirky aspect of copyright called ‘moral rights.’ These rights permit the creator of a work to be identified by name, pseudonym and even anonymously. (I tried to convince the editors that I’m pseudonymously known as Abhishek Bachchan, but to no avail.) In any event, moral rights also permit the author of the work to object to any treatment of the work that is prejudicial to his or her honour or reputation. These rights originated from the idea that some aspect of the author can usually be found in their work — a particular brush stroke, writing style, or even the mere choice of medium. Therefore, since moral rights are ‘personal’ in nature, they cannot be assigned, but may be waived in whole or in part. The most famous case on moral rights in Canada is Snow v. The Eaton Centre, where artist Michael Snow successfully argued that the Eaton Centre had infringed his moral rights by placing red Christmas ribbons around the necks of the geese in his Flight Stop sculpture (a series of Canada geese in flight, suspended from the mall’s ceiling).

Patents, on the other hand, protect inventions but do not protect ideas. They protect the practical application of an idea. There is a formal application that needs to be undertaken. If granted, the patent lasts for 20 years from the date of filing. Care, however, must be taken to not publicly disclose the invention before the date of filing, as this taints its ‘newness’ (or novelty) and, subject to certain exceptions, destroys the patentability of that invention. Generally, anything that is new, inventive and useful can be the subject matter of a patent. Although over the years Canadian courts have held that higher life forms, certain professional skills, algorithms and casino games — irrespective of how new, inventive and/or useful – cannot be the subject matter of a patent. Business methods were, for a time, also considered something that can’t be patented. However, the Canadian Federal Court of Appeal recently held that business methods could indeed be patented.

Curiously, there is no requirement to actually produce or sell an invention once the patent is granted. Some non-practicing entities (or ‘patent trolls’) literally ‘sit’ on the patent and litigate others who allegedly infringe their turf. Such is the patent game.

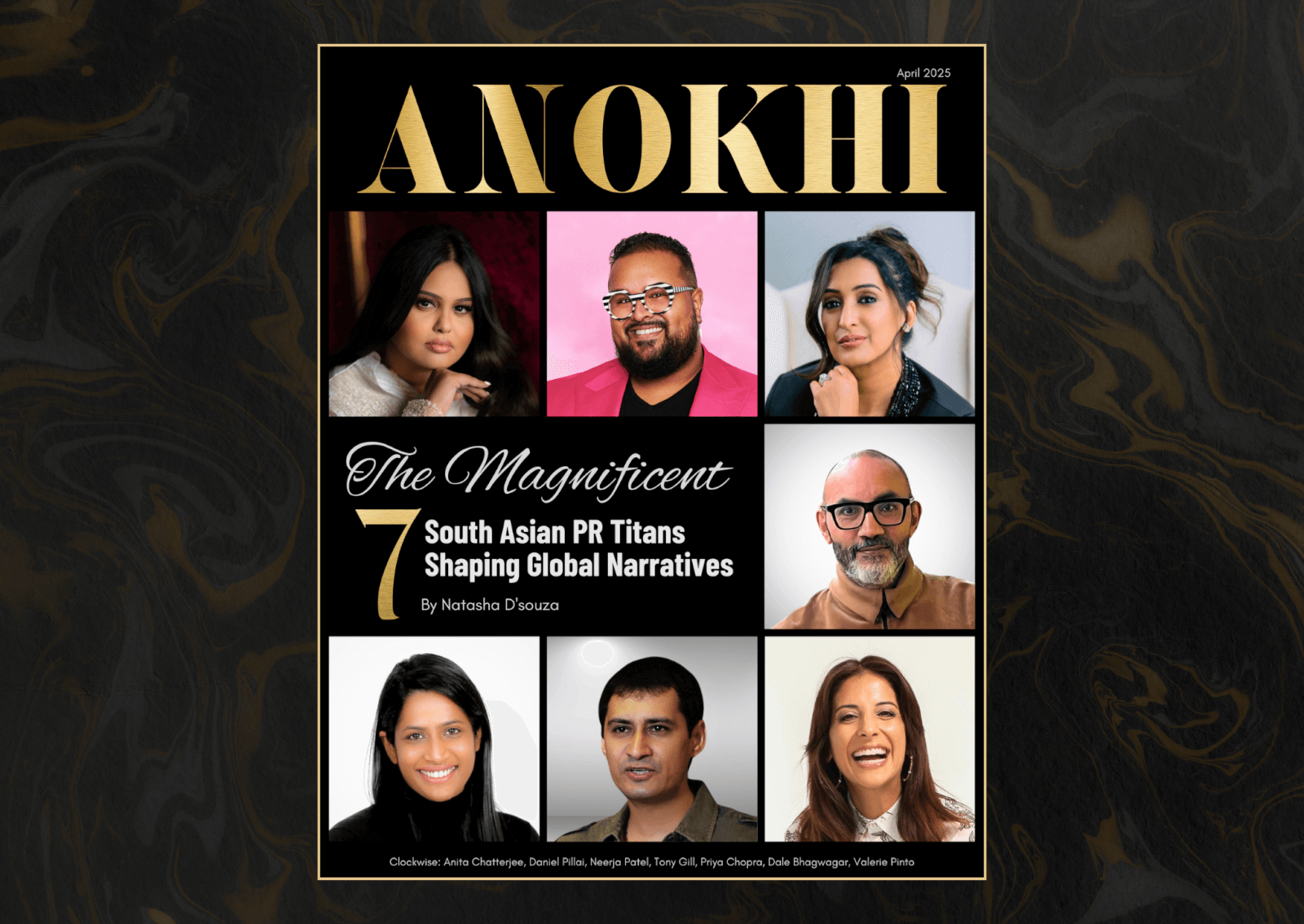

Trademarks are perhaps the most familiar intellectual property right to us. Trademarks protect the goodwill behind the goods and services we use. They serve as indicators of source and quality. They are the reasons we buy, and continue to buy, certain things. Any sign, letter, number, symbol, sound, image, phrase, word, or even smell, can serve as a trademark, “ANOKHI”, the Nike swoosh, and even the scent of Chanel No. 5 are all trademarks.

Basically, anything that can distinguish one good or service from another can serve as a trademark. By extension, descriptive or suggestive words, phrases or signs cannot serve as trademarks because they do not distinguish one good or service from another. For instance, you cannot claim a trademark over ‘cold’ ice cream, since it is descriptive of ice cream. But a fanciful variant, like ‘monkey pants’ ice cream could indeed be a valid trademark. Sometimes, however, even descriptive words or phrases acquire a ‘secondary meaning,’ whereby the public come to associate that word or phrase with a particular good or service. For instance, when someone says they’re going to Shoppers, we all know this to mean Shoppers Drug Mart, despite the fact that “shoppers” is an utterly descriptive word for, well, all types of shopping. This is one of the rare instances where it could be argued that the word “shoppers” has acquired a secondary meaning.

No formalities are required to claim a trademark right. These rights arise automatically upon use. Registration does however have some advantages. It serves as prima facie evidence of ownership and gives Canada-wide protection for the trademark. Therefore, even if the trademark owner only operates in Ontario, registration of the trademark serves to prevent others across Canada from using a similar mark. Without registration, the trademark owner receives only a limited sphere of protection. They are protected only in those areas or regions in which they operate and have goodwill.

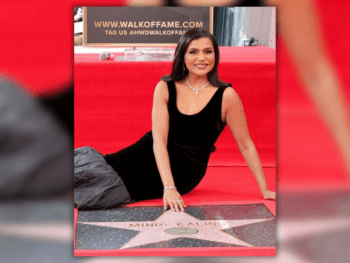

The beauty of a trademark is its longevity. As long as the trademark is in use, it can last in perpetuity, or if registered, be renewed in perpetuity. The world’s oldest registered trademark that’s still in use is the Bass Ale red triangle logo (first registered in England in 1875). And speaking of beauty, Aishwarya Rai has registered a US trademark (#3606334) for “promoting the goods and services of others through the issuance of product and service endorsements and personal appearances” and “entertainment services, namely, personal appearances by a celebrity fashion model.” Now that I’ve regained your attention, let’s briefly cover confidential information and industrial designs.

Confidential information is just that: Non-public information that’s communicated in confidence and used accordingly. Anything can, in theory, qualify as confidential information insofar as it is not publicly available. A trade secret is a sub-set of confidential information and is intended to cover things like recipes (KFC anyone?), formulae and even know-how. Trade secrets are sometimes likened to undisclosed patent rights. Confidential information (and trade secrets) can last indefinitely, insofar as the subject matter is kept confidential.

Industrial designs protect the visual appearance of products. The right protects the “features of shape, configuration, pattern or ornament and any combination of those features that, in a finished article, appeal to and are judged solely by the eye.” In Canada, the design must be registered and lasts for 10 years. (Curiously, in England an industrial design right can arise automatically, and need not be registered.)

So that’s it. Intellectual property in a nutshell. Well, not in a nutshell, but a magazine. So the next time you hear the term bandied around, you needn’t ask, “What?” Hopefully you have a better sense of its importance, features and longevity.

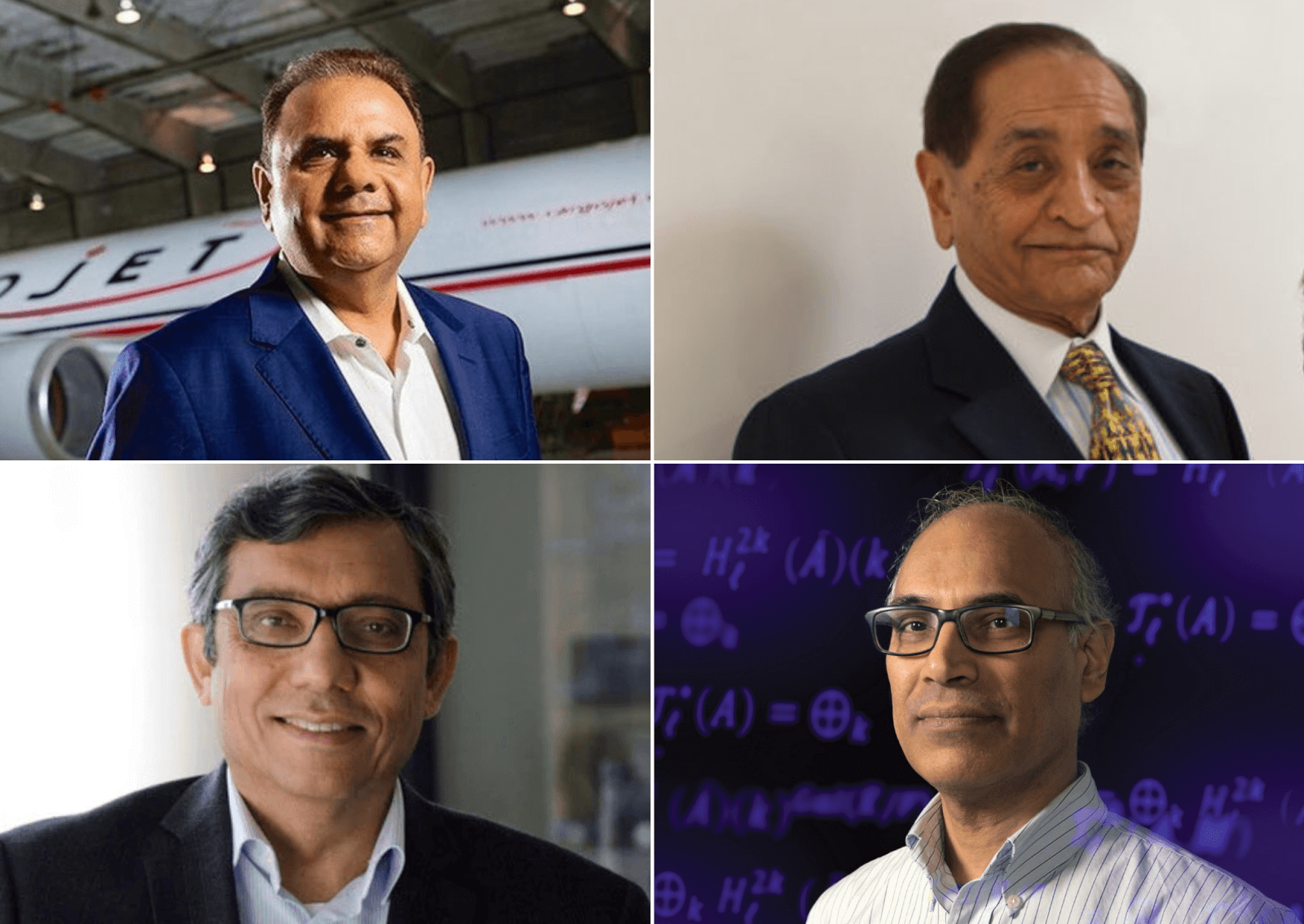

Dr. Emir Crowne is an Associate Professor at Ontario’s University of Windsor’s Faculty of Law, and Partner at Crowne PC. He received the “Professor of the Year” award in 2008, 2009 and 2010. In 2010 he also received the “Young Practitioner Award” from the South Asian Bar Association of Toronto. He can be reached at [email protected].

BY DR. EMIR CROWNE / PUBLISHED IN THE HEALTH & WELLNESS ISSUE, JULY 2012