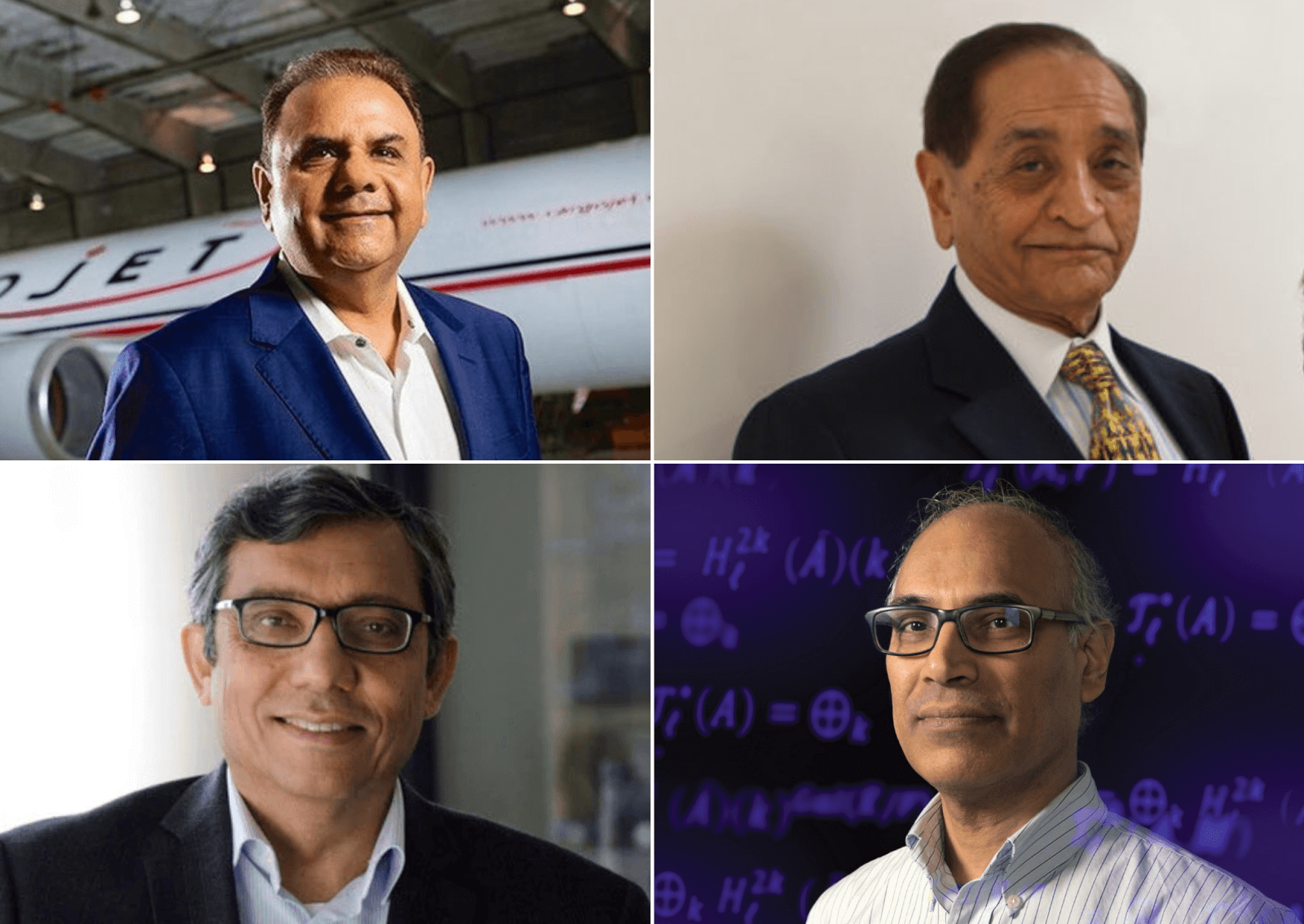

Faced with death threats and government harassment, Sri Lankan activist Kishali Pinto-Jayawardena charges on, focusing on battling sexual violence and standing up for those who can’t stand up for themselves.

She is one of Sri Lanka’s bravest women.

Lawyer and media columnist Kishali Pinto-Jayawardena is Sri Lanka’s outspoken critic of human rights abuses and one of its foremost crusaders. Her weekly legal columns in Colombo’s The Sunday Times and her several books have examined decades-long abuse of the rule of law against majority Sinhalese, minority Tamils and Muslims, and the poor in particular. She has become a formidable and legitimate critic that the government hasn’t been able to easily dismiss.

On March 8, 2014, International Women’s Day, Pinto- Jayawardena was named by Amnesty International Australia as one of the bravest women in the world, the “Malalas you’ve never heard of ” who “risk their lives every day through their determination to fi ght for other people’s rights.”

Pinto-Jayawardena keeps good company, standing shoulder to shoulder with Pakistan’s Yasmin Gull, who has defied the Taliban’s edict banning women in her region from working on social issues like education, their right to vote and access to health care; and Afghanistan’s Najia Nasim, country director of Women for Afghan Women, which runs shelters for girls and women escaping forced marriages and violence.

From her home in Colombo, Pinto-Jayawardena dissolves into intoxicating, infectious laughter when asked if she can be easily quieted under threat.

“No, no, no, no,” chuckles Pinto-Jayawardena. “(My courage) it comes from a very strong sense of stubbornness! I can’t see why anyone should be quieted by whomever.”

She is immediately awkward when complimented and shrugs off accolades. “This is a country where so many women are brave,” she says. “I just write. I write because outrage bubbles out of me. Sometimes I wish I could simmer down. Life

would be so much easier. But it is just not possible.”

She fears nothing; not the insidious, shadowy tentacles of government propagandists, outright vicious attacks or even the threatening anonymous letters dropped in her mailbox.

It is this courage, this stubbornness, that has allowed Pinto- Jayawardena to fight injustices on the frontlines of Sri Lanka’s protracted conflicts, through her newspaper column and in courts of law from Colombo to Geneva.

Her parents were a strong formative influence. Her father Brian opted to serve on remote farms in Sri Lanka’s rural belt after obtaining a doctorate in animal husbandry. After marrying her mother, Susyma, a senior teacher in mathematics and English, they moved to Kandy, a city nestled among the hills. “They hated the hustle and bustle of Colombo,” Pinto-Jayawardena reminisces. “And I cannot remember any denigration of race or religion when growing up.”

Even though her parents were devout Christians, “we had the freedom to examine things for ourselves, develop our own personalities and challenge the status quo, even when they did not necessarily agree,” she says. “I studied the injustices perpetrated by the Church on women and vowed, after I became 18, that I would not go to church, but instead, have my own private faith. It took my mother some time to understand this but she did, eventually.”

Her mother exerted a particular influence on Pinto-Jayawardena. When she passed away in 2005, her “beloved voice stilled,” Pinto- Jayawardena wrote, “My mother . . . was extremely empowering to both my sister and myself. We were brought up without any awareness that there were any limitations imposed on us because we were female.”

Pinto-Jayawardena was free-spirited, even as a child.

“You know, I have always been the diffi cult one in the family,” she says. “I take after my mother’s mother who, with two younger brothers in her wake, ran away from a staid up-country Buddhist family as a teenager and entered a Christian convent. This was scandalous during that conservative pre-colonial era. I remember her as being pint-sized, but very tough.”

The encouragement to think, to challenge, to speak up and to speak out served her well.

And it was the same rebel spirit that provoked her, as an activist practitioner, to boldly go to the United Nations Human Rights Committee in Geneva against a “very political” Chief Justice of Sri Lanka, Sarath Nanda Silva, when a lay teacher was sentenced to hard imprisonment for speaking loudly in court. He was later tortured in prison. The committee agreed that an injustice had occurred.

“It is hard enough to come to terms with state brutality,” says Pinto-Jayawardena. “But it’s worse when those who are supposed to hand out justice behave like this. I stopped going to court several years ago. I am disgusted by what our courts have become; judges are now tools of the politicians.”

Pinto-Jayawardena has also challenged the status quo by putting pen to paper in the country that the Committee for the Protection of Journalists ranked the fourth most dangerous in 2014.

In an opinion piece for The Sunday Times, Pinto-Jayawardena wrote about the chill that has fallen over free expression. “In this country, public opinion commentators may write if they wish but at their own peril, always conscious of the invisible line which, if crossed, would result in inevitable consequences.”

Pinto-Jayawardena crossed that “invisible line,” writing to the newspapers as a teenaged girl. She continued to do so while completing a law degree with honours at Colombo’s Faculty of Law. She was lucky in finding mentors from Sri Lanka’s golden age of political journalism, a time “when the media really was powerful enough to bring down governments,” she says.

“We had freedom of expression then,” she says. “Serious people encouraged me. That kind of encouragement, I think, is not all that common now. Encouragement of the young to express views that are very dissident, very, very anti-establishment, very anti-status quo.”

Although Pinto-Jayawardena has been on the receiving end of threats and insults, she remains undaunted.

“I know that I am doing right in my own conscience,” she says. “So many people appreciate the fact that there are still some who are speaking out.”

And now, as Pinto-Jayawardena turns her gaze to Sri Lanka’s future, lending her vast expertise on Sri Lankan law to international organizations like Canada’s International Development Research Centre and the International Commission of Jurists, she believes that the threat of sexual violence and the plight of the poor are the greatest injustice facing her country today.

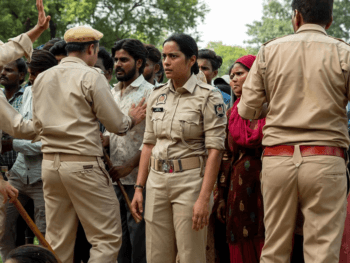

“In recent years this (sexual violence) has been coming out very much into the open, and that’s a positive sign,” says Pinto- Jayawardena. “Particularly in the South Asian context, women often keep quiet because of the social stigma.”

According to Pinto-Jayawardena, Sri Lanka is part of a rising chorus of international journalists, experts, and ordinary men and women decrying calculated sexual attacks on women around the globe, from the refugee camps of Syria and the Democratic Republic of Congo, to the barricades of the Arab Spring, and particularly in South Asia, where violent assaults have sparked widespread public outrage and forced governments to take action.

But it is by no means the only injustice taking place in Sri Lankan society today.

And when it comes to injustice, Pinto-Jayawardena does not mince words.

“The greatest injustice, I think, is very much against the poor of Tamil ethnicity, of Sinhalese ethnicity and of Muslim ethnicity,” says Pinto-Jayawardena. “Those who are rich and are powerful, even if they are of minority ethnicity, can play the system and get away with it.”

For this Sri Lankan voice, the struggle is not yet won. It may never be won. “But for the moment, speaking out is necessary,” she says.

She recalls the words of Martin Luther King, which are hanging on the walls of her study as an every-day reminder: “Our lives begin to end the day we become silent about the things that matter. In the end, we will remember not the words of our enemies but the silence of our friends.”

Isabelle Bourgeault-Tassé is a Toronto-based writer, formerly with the International Development Research Centre in Ottawa, Canada.

BY ISABELLE BOURGEAULT-TASSÉ

PUBLISHED IN THE HEALTH & WELLNESS ISSUE/SUMMER 2014