We have no problem talking about money, sex, love and the latest Netflix drama. But when it comes to mental health we clam up. Why do we have such a hard time talking about something so important? With May being Mental Health Awareness month, Dr. Gursharan Virdee, a researcher from the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, tries to understand why.

There are many issues within the South Asian community that directly impact our overall well being; domestic violence, substance misuse and sexual abuse to name a few. But the one I want to draw your attention to today is mental illness.

Rates of mental illness vary globally. In high-income countries like Canada, the U.S. and the U.K., rates range from one in four to one in five and in low-income countries such as India rates appear to be slightly lower at one in seven.

In North America, we know very little about the prevalence rates of specific mental illnesses by ethnic group, and more specifically for South Asians. Only a handful of Canadian studies have tried to tease out some of these important details. For example, a study published by Dr. Farah Islam and colleagues in 2011 identified that South Asian immigrants experience higher levels of anxiety and more stressful life events compared to those born in Canada.

However, and interestingly, Canadian born South Asians reported higher rates of poor-fair mental health. A recent study revealed higher rates of psychotic disorders reported among South Asians in Canada, in particular those with refugee status. While these rates are not as high as those for other ethnic groups, they are higher than the majority community of European background. These findings also mirror what has been found in other high-income countries like the U.K.

In our community, mental illness is one of those things that we continue to have difficulty recognizing, accepting and seeking help with early on. Many ignore and deny its impact within themselves and their loved ones. The silence around mental illness exists in all communities to varying degrees, but there are some cultural factors that make the experience of being South Asian with a mental illness very unique, which makes the ability to seek help early on challenging and in some cases impossible.

I grew up in a small town in the South East of England where there was a large Punjabi Sikh population and saw this same denial manifested there. I moved to Mississauga, just outside of Toronto in Canada, and have continued to see the same thing here. As I began to unpack the layers of silence, I was met with a number of interesting values and beliefs that reinforced the silencing.

Broadly speaking, the South Asian community operates within a collectivist framework – meaning that we tend to focus on the community perspective and not the individual. Statements like “what will so and so say?” and “we can’t say anything because it will affect our family honour” are some everyday examples of collectivism impacting our communities.

In some cases there is also a different understanding of mental illness. In my research on South Asians with psychosis, a number of participants and their family members understood the experience of hearing voices and other symptoms as a spiritual experience or gift from a higher power rather than an illness. As valid as these perspectives are, when not a positive spiritual experience, this resulted in delays to seeking help, often leaving it until the individual’s mental health had further deteriorated or exhibited challenging behaviour in the home.

It’s not surprising that recent research conducted in Toronto found South Asians along with East Asians were more unwell when arriving at hospital. It is important to consider the mind-body-spirit connection that frames well-being in many South Asian cultures and that we do not leave our beliefs at the border when moving to a different country.

When I think about the silencing of mental illness among South Asians, it would be unfair to leave the conversation focused on community-level issues. We don’t function in a silo and are constantly interacting with others. This is where the impacts of being a minority immigrant community come into play, highlighting wider societal and systematic effects.

Being a ‘model minority’ community creates a further layer of complexity for the South Asian diaspora, whereby a number of stereotypes are imposed by the majority community – for example being hard working, productive, obedient citizens who do not cause any problems. Somewhere along the journey we have internalized these stereotypes and I have come to believe that it prevents us from asking for help as a way to maintain this ideal which ultimately bolsters one sense of belonging.

It’s not just one area that requires tackling, and we need to work together to identify community and service level issues. At the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH) in Toronto we are doing just that by raising awareness and funds for research to develop culturally-relevant supports for South Asians.

We are working with community leaders and agency partners, including the faith sector, to raise awareness and address the stigma surrounding mental illness, and develop tools to support the unique needs of our community. This line of work led to the development of The Collaborative for South Asian Mental Health, a CAMH-led initiative that bought together researchers to advance mental health equity for South Asians through research and advocacy.

One way we are doing this is by participating in the Mississauga Marathon on May 6 to 7. Our call to action focuses on each of us to be a part of the change in whatever way we can, whether its opening up about our own experiences; asking people how they are feeling and genuinely taking an interest to listen with care and kindness as other begins to share their stresses and worries; thinking about the language we use when speaking about mental health; or if in leadership roles, to capitalize on that platform and highlight the need for culturally appropriate services.

Over the past few years there has been increased momentum from within South Asian communities, with leaders in various sectors stepping up to address mental health related stigma. For example, in 2015, Deepika Padukone opened up about her battle with depression which ultimately led to the launch of the Live Laugh Love Foundation in India. Raising awareness is key but we need to ensure people have the right services available to them as they embark on a journey of healing and recovery.

For more information about how you can contribute to the fundraising efforts please visit: https://www.supportcamh.ca/getinvolved/southasianmentalhealth.

Dr. Gursharan Virdee is a trained psychologist (UK) currently working as a researcher at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. Her research focuses on expanding our understanding of mental health recovery and psychological interventions for diverse populations, youth and individuals with severe mental illness. Dr. Virdee co-leads The Collaborative for South Asian Mental Health, and is on the board of the Regional Diversity Roundtable, Peel.

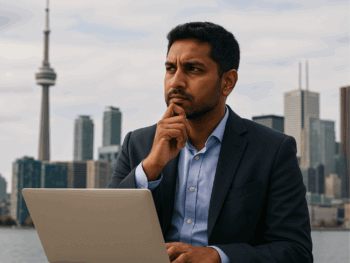

Main Image Photo Credit: The Chronicle Herald

Gursharan Virdee

Author

Dr. Gursharan Virdee is a trained psychologist (UK) currently working as a researcher at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. Her research focuses on expanding our understanding of mental health recovery and psychological interventions for diverse populations, youth and individuals with sever...

COMMENTS

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE

Newsletter Sign Up

Subscribe to our FREE newsletter for all of the latest news, articles, and videos delivered directly to your inbox each day!