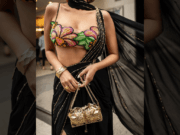

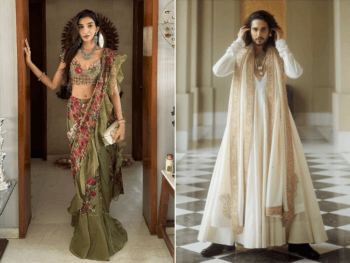

An Art Installation Explores The Patriarchal Domination Of The South Asian Bride

Apr 14, 2017

An artist dissects the cultural practices of the Indian bride leading up to her wedding day.

Born to activist parents, award-winning artistic director Ms. Mutta (Rakhi Mutta) creatively explored navigating the expectations and processes that are associated with the generations-long rituals of North Indian marriage. A one-night-only, multi-disciplinary performance in Toronto, The Good Indian Bride aimed to physically embody the painful legacy of patriarchy over the bride both in the diaspora and the subcontinent.

The concept and motivation to create the live performance of The Good Indian Bride came from a photography exhibit of the same name that was featured at Nuit Blanche 2015 in Toronto and the 2015 Feminist Art Conference in Toronto.

A packed room of captivated wedding guests awaited patiently to explore three different rooms that hosted brides-to-be partaking in different wedding ceremonies. Ms. Mutta challenged her guests immediately by presenting a very young bride partaking in wedding preparation led by two adult women. The dark and eerie backdrop was in stark contrast to the young bride dressed in her best clothes and finest jewellery, being pampered to appear her most beautiful. However it was clear that the bride-to-be’s expression doesn’t appear joyful, despite the fact that she has been told her wedding day is meant to be an auspicious event.

The attendees are forced to see this young bride and empathize with her sadness and isolation. Ms. Mutta shares that the pressure on a bride to look flawless and elegant is drilled into her brain from a very young age, leading to management of weight, etiquette training and even bleaching of her skin to appear fairer.

Next the guests move into the bedroom where the new wife is anxiously awaiting her new husband to partake in Suhaag Raat, or the loss of her virginity on her wedding night. Adorned in the traditional red wedding garbs and surrounded by decorations of hanging garlands of flowers, she grasps a glass of saffron almond milk to offer to her husband when he enters the chamber. He is expected to drink half and offer it back to her, to ensure they can conceive once the marriage is consummated.

Ms. Mutta disrupted the intimacy of the wedding night from being a pleasurable experience for the bride by illuminating how hauntingly demoralizing it is for her to be reduced to a vessel for procreation, leaving little if any room for her to experience pleasure like her husband. Again, the painful inequities of a man and woman in marriage seem clear to see for onlookers.

Finally, the wedding guests are presented with an abstract representation of the bride and her offering of a dowry. Quite literally, the two brides wore dresses made of Canadian $50 bills. Not only does this allude to Ms. Mutta’s own Indo-Canadian identity and diaspora, but comments on the value of the bride being directly tied to the value of her dowry and responsible for many undocumented murders of Indian women.

Ms. Mutta’s poignant commentary in this room was that while women are historically not allowed to earn money, dowries have been a long-withstanding practice to offset the costs associated for the groom’s family to take care of the bride. In fact, due to the act of dowry giving, gendercide (the killing of a fetus due to sex) has become all too common an everyday reality in North India. Over the course of a lifetime the bride’s family can be solicited for more money to reduce the mistreatment and abuse of the bride, and perpetuates a very dangerous cycle to disadvantage The Good Indian Bride.

Main Image Photo Credit: Indian Roots Daily