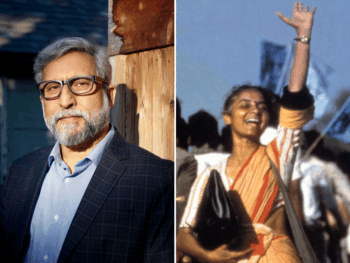

Deepa Mehta Takes On Rape Culture In TIFF Drama “Anatomy of Violence”

Dec 17, 2016

The Canadian filmmaker goes beyond the headlines of the infamous 2012 Delhi gang rape, with a raw, unsettling drama that aims to expose the pervasive squalor and toxic patriarchal forces that turned six men into monsters.

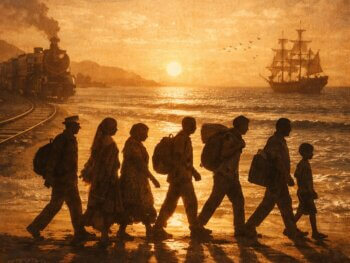

On December 16, 2012, a 23-year-old physiotherapy student was beaten and raped in broad daylight by six men cruising the streets of Delhi in an off-duty bus — “brutality” doesn’t even begin to describe what she endured that day. After clinging to life in hospital for two weeks, she succumbed to her injuries. It’s a crime that spurred outrage and made headlines around the world, and incited protests in India from a public fed up with institutional apathy toward this all-too-pervasive stain on their society. The tragedy and ensuing uproar spurred changes to the criminal code, including more severe sentencing for sex crimes and an attempt to increase safety on public transportation — one of the most common venues for assault.

And yet, reports of rape have risen. Clearly, any solution needs to go beyond amending a few laws; clearly a more profound transformation is required — one spurred by understanding the real root of the problem. That’s what makes Deepa Mehta’s dramatic revisiting of that four-year-old attack as timely as ever.

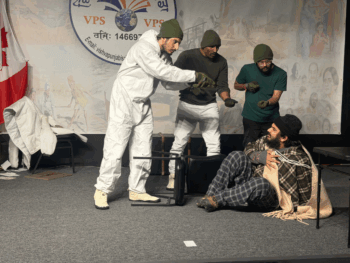

Debuting at the Toronto International Film Festival this past fall, Anatomy of Violence doesn’t focus on the incident itself; rather, it explores and indicts the society that would allow it to happen, imagining the lives of the six rapists — the squalor, anger and toxic patriarchal forces that, over the course of their lives, forged them into men capable of committing the unforgivable, without remorse.

In an interview that, as the director herself pointed out to us, took place on the four-year anniversary of the Delhi assault, Mehta offered ANOKHI a little more insight into a film that’s deeply challenging in more ways than one.

“Like most people I was outraged by the crime and what it said about a culture where patriarchy reigns and inequality of gender leads to lack of accountability across the board,” Mehta begins. “I thought of doing a film using this tragic incident as a framework two years ago; I knew even then that I had no desire to re-victimize the victim, but rather felt a compulsion to explore ‘What makes a rapist?’”

To that end, she journeys way back to each fictionalized attacker’s childhood, to the moment where a seed of the act that would come to define their lives was planted — either by learned behaviour or being sexually assaulted themselves. In one of the film’s more striking choices, the adult actors (Vansh Bhardwaj, Davinder Singh, Jagjeet Sandhu, Mukti Das, Suman Jha, Mahesh Saini) also portray their characters as children.

“We wanted to explore the most traumatic moment in the lives of the rapists amongst other aspects of their lives. All the ‘traumatic’ stories evolved from some childhood incident in their lives and were sexually or physically violent in origin,” Mehta explains. “It would have been extremely manipulative to use child actors, as well as uncomfortable. So we collectively made the decision to have the adult actors play themselves as children. Also, that distance — a character looking at himself through time — gives the piece a certain objectivity.”

From there, we follow each through adolescence and adulthood, as their isolated stories gradually converge, those traumas festering and expanding, until the fateful day they all pile into a bus for a drunken birthday party and head on the prowl.

Mehta and her actors, along with theatre director Neelam Mansingh Chowdhry, engaged in extensive workshopping before filming, wherein each performer was given a great deal of freedom to improvise their characters’ personal journeys and psychological evolution from innocent child to remorseless rapist and killer.

But as much as the film sets out to understand these men, the light that they snuffed out is ever-present in the film — with Mehta periodically cutting to the victim (played by Janki Bisht) delighting in the company of family, friends, co-workers and a love interest in the days leading up to the attack that will soon snatch her away from them.

“Anatomy of Violence is [the role] of societal mores in the nurturing of men who perpetuate violence against women. The six rapists are totally accountable for their brutal crime. The question is what we as a society can do to prevent the proliferation of these monsters,” Mehta says. “To juxtapose [the victim’s] life — her hopes, ambitions and utter normalcy — with the dysfunctional lives of the rapist seemed like a categorical imperative.”

Anatomy of Violence, as you may have guessed, is not an easy watch. It unsettles not only in its subject matter, but in the raw, unflinching, experimental, altogether anti-cinematic way in which it’s filmed. At a recent public screening at the Whistler Film Festival, Mehta and producing partner David Hamilton confirmed it: they didn’t make this film for the purposes of “entertainment.”

Mehta expanded on the point during our chat: “The nature of violence against women is brutal. To make a film that deals with the exploration of this intensely horrific fact in a manner that makes an audience member uncomfortable is a given. How can it be otherwise? The film has no ‘frills’ that might mitigate the horror that unfolds before us more palatable — no music score, no dance numbers, no fancy lighting, no smooth camera moves. The film is as raw as its narrative. And if that brings a viewer closer to the reality of what we as members of a society perpetuate on each other — then I feel our goal to start a dialogue of prevention has begun.”

Indeed, it’s a dialogue they’re taking steps to continue beyond the film’s current festival run and yet-to-be-determined theatrical release, in an effort to impact the conversation on this global problem.

“The primary reason to make Anatomy of Violence was its potential to be used as a tool to perhaps catch a glimpse about what causes violence against women. The question is an extremely complex one and has equally complex answers,” Mehta explains. “I guess I didn’t want to be daunted by this uphill task by sitting on the sidelines, lamenting about the horrific inequality between genders, the nauseating cultural mores like patriarchy, the fury of powerless men, etc. I wanted to show the landscape where they breed, so hopefully we can have, someday in the near future, a society that is humane. Doing my small bit, I guess.

“The good news is that our efforts are actually having an effect. Iceland, for one, is going to use the film in their curriculum for senior school students; panels in universities; screenings in central India, Turkey, Philippines, Thailand and Cambodia — from village to village. We are working to do the same in Canada, U.K. and the U.S. Let’s not forget violence against women knows no geographic boundaries, class or colour.”

Main Image Photo Credit: www.tiff.net

Matthew Currie

Author

A long-standing entertainment journalist, Currie is a graduate of the Professional Writing program at Toronto’s York University. He has spent the past number of years working as a freelancer for ANOKHI and for diverse publications such as Sharp, TV Week, CAA’s Westworld and BC Business. Currie ...

COMMENTS

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE

Newsletter Sign Up

Subscribe to our FREE newsletter for all of the latest news, articles, and videos delivered directly to your inbox each day!