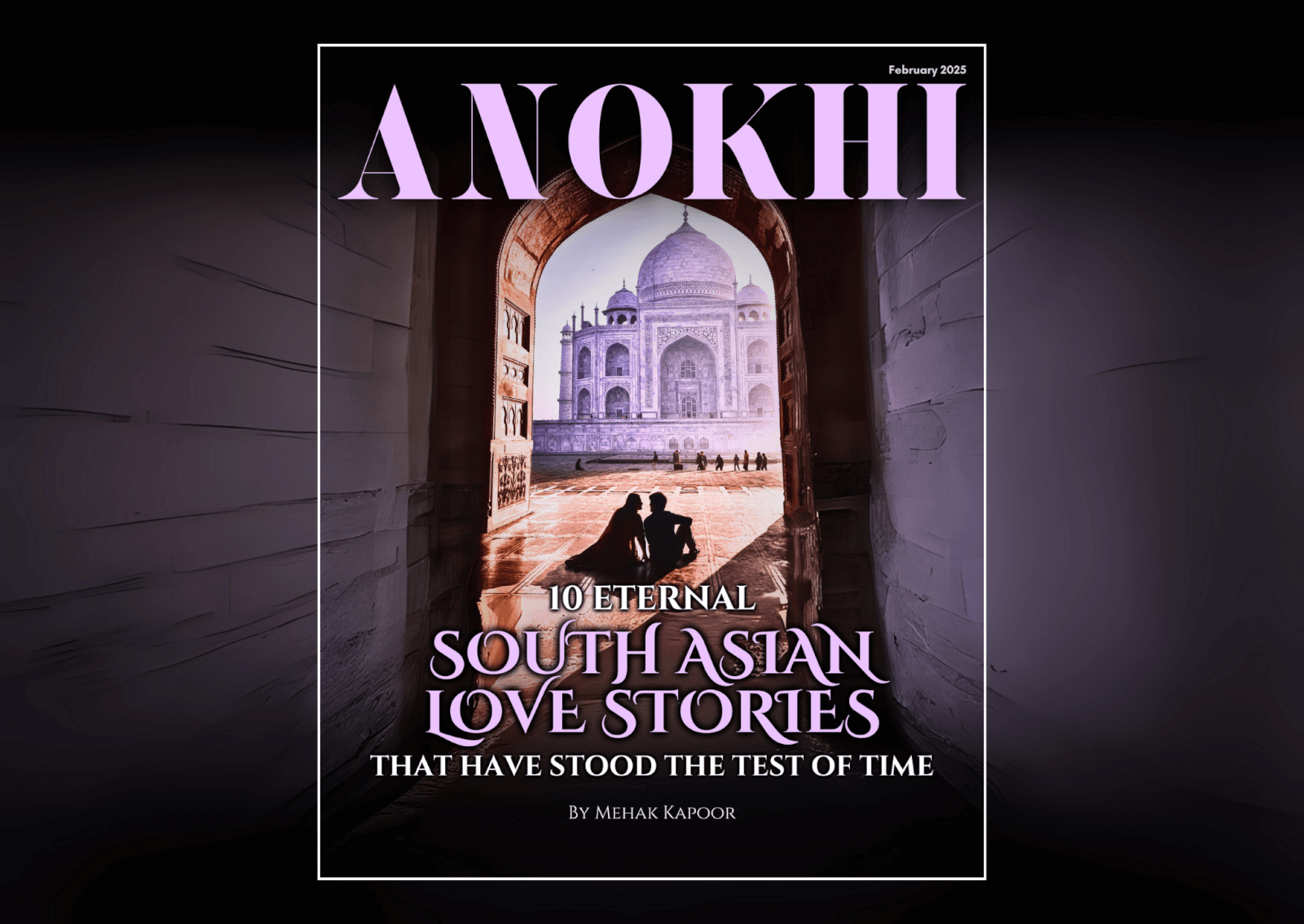

Imagine coming to a new country. Your old way of life is gone. Now you have a new one to adapt to. How do people here think? What’s considered normal? How should I act?

It’s your old mentality versus the new one. But you’re young, so you still have some growing to do. But your parents? Their ways are pretty much set in stone.

So while you may have left the old country, the old country hasn’t left your parents. And you live with them. What can possibly go wrong?

We sat down with three women (names changed, of course) who lived in India and then immigrated to Canada before the age of 18. Sona, now 34; Malika, 38; and Chiti, 21 all grew up in households where mom was front and center for the child raising. Dad was frequently away on business, leaving Malika and her siblings under the rule of mom. And everything revolved around mom’s expectations. The same was true for Sona and Chiti.

“My father was a stranger to me,” Sona tells us. “I had talked to him on phone from overseas but I didn’t know much about him except that he was my father.

Malika describes the childhood relationship she had with her mother as “a dictatorship.” Mom’s mantra was, “Children should be seen and not heard.”

Malika laments, “Indian girls are brought up to please others. You had to be self-sacrificing to be considered good.”

Cultural challenges exist especially with daughters.

Image Credit: dayatrust.com

For Sona, this type of in-house oppression didn’t carry over well into the new world of North America. “I just wanted to be able to do a lot of things without any restrictions and barriers. That led me to be a little feisty and rebellious because I didn’t like being told no all the time.”

“In my culture everyone in the community is so involved in your life that you have to be careful what kind of move you make just in case someone’s watching, because then they will tell your parents or spread rumors about you to the community. So your parents’ respect was on the line, and your parents’ respect is the most important thing in a child’s life. You can’t do anything that would in any way bring shame upon them.”

Sona believes that this conflicts with North American values. “In India, you structure your life around the community. But in North America, you structure your life around yourself.”

Relationships

“I was confused when I first arrived in Canada,” Malika says. “I was 16, and the culture shock fed my insecurity because I wasn’t sure how to behave. That could get you into situations that are not true to you as a person. You try and fit into a new set of values that may not be in line with yours, but you’re forced to try and find a middle ground so that you can feel secure in yourself.”

Malika told us, “Being the good Indian girl I was raised to be, I was really self-sacrificing when I first started dating.”

“In India,” Sona says, “Men are handed opportunity. They expect it. It's part of the culture. I’ve seen men immigrate here from India, and what’s seen as authoritative there could be seen as presumptuousness here. Women, on the other hand, are seen more as servants.”

The lingering childhood teachings stayed in Malika’s head, and spread to areas of her life her parents didn’t consider. “If a guy wanted to kiss me, I would let him. He wanted to touch me, I would let him. Sometimes I would have sex with a guy just to make him happy.

"But I changed that. I had to learn the hard way, but I did change it. I think it's important for everyone to get to know people in their communities who have gone through similar integration struggles, and then you learn from them. Ask them questions. It's okay to speak up. Better to ask a silly question than find yourself in a horrible situation."

Sometimes standing up for yourself is key when adapting to new situations.

Image Credit: shutterstock.com

Work and Money

So what happens when the kids get more freedom? More money? A career path?

“When we first arrived in Canada my parents managed all of my money,” Malika says. “Any cheque I got went straight into their account, not mine. I didn’t have one until I moved out. Needless to say, they were not happy about either of those facts.”

“My mom still opens all of my mail,” Chiti says. “Every letter, every form, every paycheque. She knows exactly how much money I make.”

As for making money, all of their parents had the exact same idea. The highest profession in Indian culture. “They wanted me to be a doctor, of course,” Malika says with an eye roll. “And when I told them I was going to be a college professor I think their opinion of me dropped a little bit. Wouldn’t be the first time.”

“I’m in medical school right now,” Chiti says. “During exam time I under eat and vomit from all the stress. If I don’t become a doctor my parents will practically disown me. Seriously.”

She adds, "But it will all be worth it in the end. Growing up in an Indian community within Canada it's pretty clear that my parents will be living with me for most of my life. When they're older I'll probably be taking care of them, and being a doctor I'll be able to support them. It'll be a small thanks for giving me a life in this great country."

Greater Generation Gap

A broader generation and cultural gap also exists in joint family situations where multi-generations of families exist under one roof. The reason for a multi-generational can be multi-faceted: It can be cultural or simply economical.

According to Statistics Canada, South Asian grandparents are a whopping eight times more likely to live with their grandchildren. In 2014, the U.K. recorded "households containing two or more families were the fastest growing household type increasing by 56 per cent to 313,000 households." According to the AARP and Pew Research Center, in 2008 "49 million Americans or 16 per cent of the U.S. population lived in households that contained at least two adult generations or a grandparent and at least one generation.

Sure parenting can be challenging when raising kids in a culture entirely different than your own. However add living with your parents to the mix and this can result in various forms of cultural rifts when it comes to home country versus new country and grandparents versus grandchildren.

Cultural battles can even fall into the unsavoury side. Farida Bano Ali, a Vancouver resident who works with female domestic violence and abuse victims, stated that she frequently sees live-in South Asian grandparents get taken advantage of for babysitting and also for their money. She’s seen cases where children of senior citizens take away their parents’ social security cheques.

Canadian stats when it comes to multi-generational households.

Image Credit: vancouversun.com

How We Coped

"The way I've dealt with it," Malika says, "I've just come to accept the fact that I can't change my parents. They are who they are, and trying to convince them to think otherwise just gets us nothing but arguments and headaches. You have to make sacrifices where you can, because at the end of the day, they are your parents."

Sona concludes, “I always fought for my rights as a girl. It did take little convincing but, eventually my parents understood that Canada just has a different way of life. It’s impossible to say that they should have adapted sooner, but we all have to learn at our own rate.”

Taras Babiak

Author

Taras is a freelance blogger, video editor and screenwriter. He is the co-writer of "Made In Bali," which recently won Best Short Film of the year from the Director's Guild of Canada.