Taking an historical look at traditional South Asian beauty treatments

It’s no secret that women have been obsessing over their beauty for thousands of years. Whether it was Romans and their scented baths, the Chinese binding the feet of young girls, or European ladies strapping themselves into corsets, beauty has been a focus in many cultures for centuries. And while some beauty traditions have remained constant, others have changed over time. Almost every South Asian kid can remember their grandma massaging coconut and amla oil through their hair. Sure, the modern day equivalent is a “coconut-enriched moisturizing conditioner,” but the reason—and result—is the same. Here’s a look at three of our favourite beauty traditions that are crossing cultural boundaries:

1. Mehndi

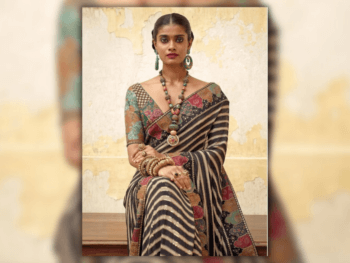

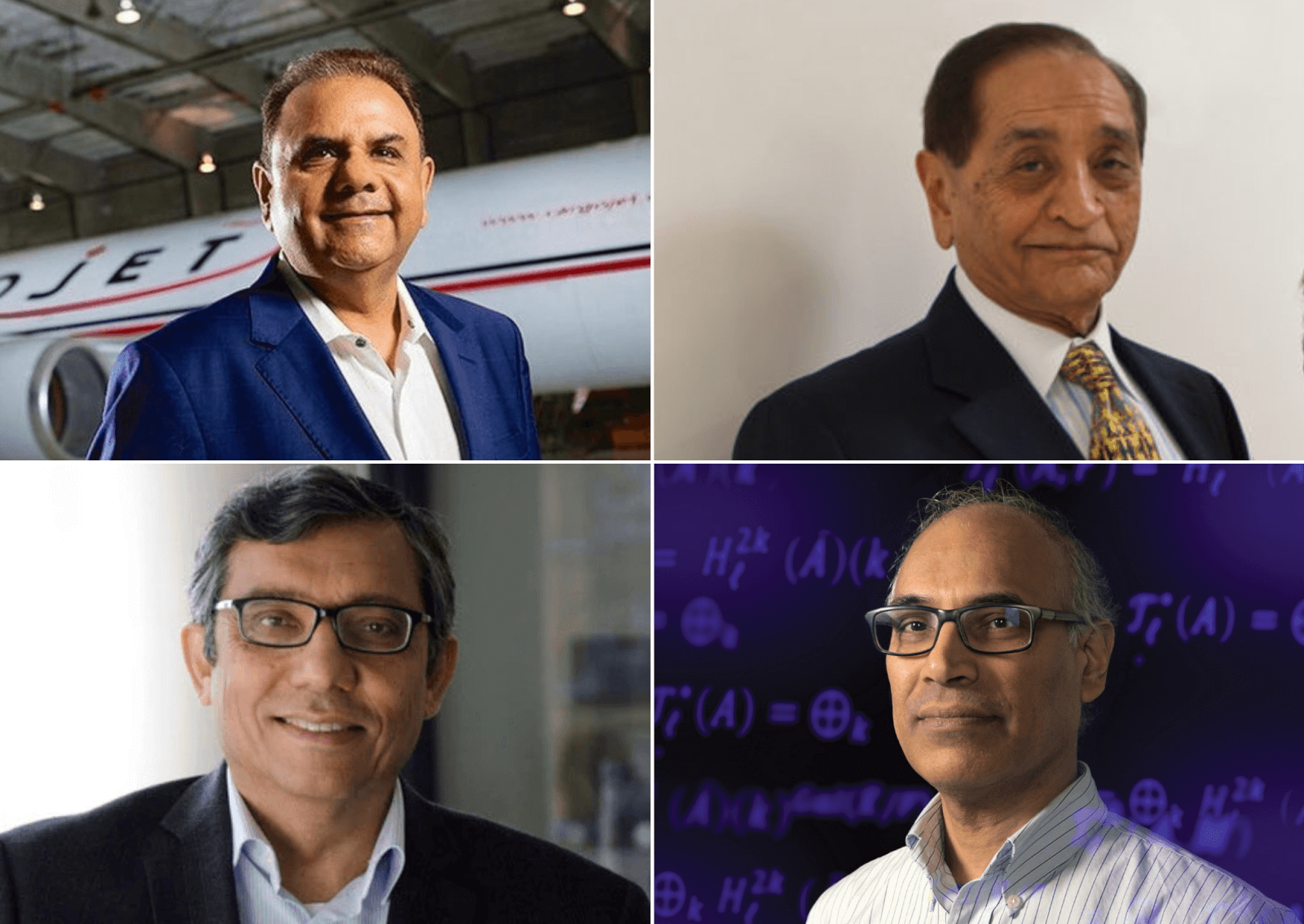

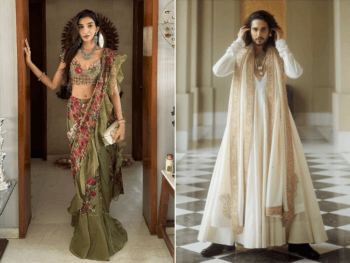

You would recognize it anywhere. The rich, dark burgundy-stained hands of a dhulan. The laughter as ladies gather around, their palms stretched out as another woman traces designs with a blackish paste from a cone. The application of mehndi, or henna as it is sometimes called, is an ancient tradition hailing from South Asian and Middle Eastern culture.

A potential origin is thought to be Egypt, where there is some evidence that henna was used on the fingers and toes of pharaohs prior to mummification, the idea being that body art would ensure their rulers recognition in afterlife. In South Asia, however, it has no religious signification; it is simply meant to enhance beauty, as a form of jewelry. One theory is that mehndi was brought to South Asia by the Mughals in the 12th century. Shah Jahan’s queen Mumtaz Mahal, in whose honour he built the Taj Mahal, was reputedly the first Mughal queen to be decorated with henna. To this day, mehndi artists practice their craft outside the Taj Mahal in her honour.

In her book, Mehndi: The Art of Henna Body Painting, Carine Fabius suggests an alternate theory. She says mehndi started out as an answer to the need for air conditioning in the hot deserts of Rajasthan, Punjab and Gujarat. The henna plant, Lawsonia Inermis has several medicinal properties, chief among them its ability to cool down the human body.

People from these areas would dip their hands and feet in a mud or paste made with the crushed leaves of the henna plant. When the mud was scraped off, they noticed, that while the colour remained visible, their bodies felt cool. Eventually, Fabius writes that some women grew tired of bright red palms and found that one large central dot in the palm of the hand had the same effect. Other, smaller dots were placed around the centre dot, which gradually gave way to the idea of creating artistic designs.

Mehndi initially used to be applied by dipping a stick in the henna and then tracing designs. In the last two decades, most artists have made the switch to cones, which allow them to trace more intricate designs.

As manager and lead artist at The Touch of Dimples, a Toronto-based bridal studio, Dimple Shah can whip out an intricate design in mere seconds.

“Brides are more interested in getting traditional designs with wedding themes incorporated in the designs,” she says. There are plenty of design options; from fertility motifs like mangoes, wedding scenes such the bride leaving in her doli or the barat arriving, to thicker Arab floral designs and African styles that tend to be more geometric.

And there some fun traditional myths associated with mehndi. For example, if a groom cannot find his name written in the mehndi decorating his bride’s hands, it is said the woman will have the upper hand in the marriage. And the darker the colour of the mehndi, the stronger the relationship between the prospective newlyweds is expected to be.

Mehndi decorations also became fashionable in the West in the late 1990s, where they are sometimes called “henna tattoos.” Shah says many customers like the idea of a not-so-permanent tattoo—a chance to experiment—with more culturally neutral designs such as butterflies or Celtic designs. Celebrities such as Madonna, Sting and Gwen Stefani, amongst others, have popularized this ancient art in the West.

2. Turmeric

One of my youngest memories is my dadi smearing a turmeric paste all over my face and extolling the virtues of one said cream, “Vicco Turmeric.” Apparently, it would make my skin glow. Turns out, she was right. It did come in handy, especially during my pimply teenager phase.

Turmeric has a variety of names in Sanskrit, such as “Haridra,” meaning “the yellow one,“ or Gauri, an South Asian name meaning “the one whose face is light and shining,” or “Kanchani,” which is literally the “Golden Goddess.”

Perhaps it should come as no surprise then that turmeric, or haldi as it is known in Hindi, is often used in South Asian beauty traditions, including wedding ceremonies. Although it is practised in many subsets of South Asian cultures, Bengalis have a particular name for the yellowing ceremony called gaye holud, during which turmeric paste is applied to make the bride and groom’s skin glow and soften. The ceremony is considered auspicious and is meant to purify both bride and groom before the big day, symbolized by the colour yellow, which denotes sanctity.

The plant turmeric, Curcuma Longa, grows wildly in the forests of Southeast Asia and comes from the ginger family. Probably originating from India, turmeric has been used in India for at least 2,500 years. It may have been cultivated first as a dye, with use as a spice coming later. Turmeric, in the form of a paste is often prescribed by practitioners of Ayurveda for beauty care as well as to treat various skin ailments. In Ayurvedic practices, turmeric is used readily as an antiseptic for cuts, burns and bruises as it is essentially an antibacterial agent.

Turmeric paste can also be used to ward off wrinkles, prevent tooth decay, get rid of acne and unwanted hair (supposedly) and dry skin. Some sunscreens have also started using turmeric as an ingredient. Of course, one of its main advantages is that it is readily available, inexpensive and requires no skill to apply!

3. Threading and Sugaring

South Asians tend to be blessed with thick, dark, voluminous hair—the envy of many a woman. But for better or worse, that also applies to body hair as well. Hair removal can be the bane of many a South Asian. So it’s not surprising that we have our unique hair removal techniques.

“Threading is a centuries-old technique of hair removal,” says Jennifer Pesce, New York City’s celebrated hair removal expert and brand director at Shobha hair removal salon. That perfect “Indian arch” of the eyebrows is usually attainable only with the precise work of a threader.

“Although the exact origin (of threading) is not clear—it has also been found in Russia and China—it has been passed down as a South Asian beauty tradition for many generations,” she says. Threading is also quite popular for women in Middle Eastern countries, with some folks suggesting it actually originated in Turkey nearly 3,000 years ago. The technique is called “Khite” in Arabic and “Fatlah” in Egyptian.

Ancient Egyptians believed that body hair was unacceptable and unhygienic, which is why they developed a variety of hair removal techniques including threading, waxing and shaving. The idea was to emulate the perfect form of gods, who were often depicted as hairless.

Today, threading hair removal is the hottest method of facial hair removal and continues to grow in popularity worldwide, although it can be sometimes tricky to find a threading specialist outside of Middle Eastern or South Asian neighbourhoods.

For those unfamiliar, threading is by far the gentlest form of hair removal, especially compared to waxing or plucking with tweezers. It’s a fairly simple process that involves pulling a piece of thread twisted like a lasso across unwanted hair. Pesce says threading’s popularity stems from its versatility. “Often times clients will come for full face treatments to remove the peach-fuzz hairs that cannot be removed with other methods like waxing,” she explains, noting it can also be done anywhere on the body. Threading the entire face is widely spread amongst Iranians as well, but it was originally practised when a woman was getting married. In ancient Persia, threading was a sign that a girl had reached adulthood, akin to “coming out.”

Another not-so-well known but equally effective method of hair removal is sugaring. “Sugaring is actually the forefather of modern-day wax,” Pesce says. “It is also an ancient method of hair removal with various origins, mostly in the warmer climates like South Asia, Mesopotamia and Greece.” Even Cleopatra is reputed to have used this method!

The process is very similar to waxing, but the sugaring gel is all natural – it’s so natural you can even eat it! It’s made of just sugar, lemon juice, glycerine and water. Some theorize that sugaring may have been discovered when a sugar paste was formed to dress a wound. The removal of the paste would also rip the surrounding hair out. The technique is described in Egyptian hieroglyphics and in writings from the Turkish Empire. But as shaving leaves the hair tougher, sugaring became eventually the preferred method in the Middle East for hair removal as it caused less skin damage than wax and had more permanent results. Hence, it has alternatively been called “Persian waxing.” Today, threading and sugaring are making waves in the West with celebrities such as Liv Tyler and Salma Hayek as big fans. The two methods have gone global, but remain particularly popular in the Middle East, South Asia and some Mediterranean countries.

BY: TAMARA BALUJA / PUBLISHED: MAY 2010 ISSUE

(PHOTO COURTESY OF SHOBHA)