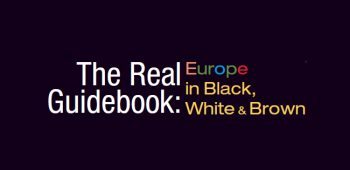

Beginning in Vienna and then heading through Hungary, Romania and Ukraine before eventually setting out to the Caucasus and Central Asia, travel writer Robert Kaplan noted that traveling east meant taking steps down in development. Crossing each border meant an increase in poverty, corruption, dysfunction and an overall step further away from Europe. I was now doing that trip in reverse.

Romania was in some ways the weirdest place, and the only one that drew me back twice. It’s not surprising to any backpacker who’s been there: the land of Dracula and Ceaucescu is also the home of some truly frightening buildings, both medieval and modern, including the Palace of the Parliament, the world’s second largest building (after the Pentagon). Then there’s the unusual language (closer to Latin and ancient Roman, hence the name), horse-drawn carts, stray dogs, hundreds of thousands of orphans and of course, gypsies.

Known as Roma, gypsies are universally despised throughout Europe: at best considered a nuisance, at worst, enslaved and massacred over the centuries since first migrating to Europe from India a thousand years ago. Usually homeless and unemployed, they came close to picking my pockets a few times. I’d seen sterner authority figures chase them away across the continent, but only here, redolent in shiny red and yellow tunics, did they seem remotely dignified.

Almost from the start, we tumbled into an incongruous mix of pasty pale Latins and some apparently long lost cousins in Bucharest and Oradea. A homeless man who spoke English befriended us the second time I was there. He haughtily shooed away a few drunk gypsies who might have seen me as one of their own who had made it big, but this ended up being the only place in Eastern Europe where I could stroll around with relative impunity. More so than sleepy Bulgaria or bustling, bomb damaged Serbia next door.

In Poland, I spent a week with my friend Davesh, also of Indian descent…as were half his medical school classmates. For a fraction of the cost of Western educations with arguably similar standards, many North Americans weren’t just spending a semester abroad, but getting their entire degrees there. Everyone in the Englishspeaking division was either of Polish or surprisingly enough, Indian American, Indo-Canadian or even Fijian descent. I spent most of my time in their frat house environment but as four or five brown guys out and about Warsaw, we must have been quite the sight. At least for the Polish merchant who inexplicably flew into a rage and started screaming racial obscenities at Davesh in particular (ignoring the rest of us and the young West African man hawking his own wares a few stalls away) at a large bazaar of pirated goods. It must have been his height; one of the few times I was refused entry into a nightclub was with my short friend later that week without the “membership cards” other Polish folks didn’t seem to need.

At the time of my trip, Poland, Hungary, Slovakia, the Czech Republic and others were voting on membership to the biggest, most comprehensive club around – the European Union. Like the Baltic States, these four countries were leaving their poorer, more corrupt, neighbours behind. Sure, one still had to be weary about being gassed on overnight trains and running into the occasionally disgruntled skinhead, but new shopping malls, highspeed trains, and foreign cars were approaching the norm rather than the exception, at least in the big cities.

It wasn’t just Euros and dollars crossing the border either. The further west I went, the more tourists I ran into in these increasingly saturated hotspots. Even smaller places, like Bratislava, boasted a few Pizza Huts and Benetton stores. In more prominent centres, my ears were assaulted with my own language at the most pristine landmarks, like Prague’s immaculate Charles Bridge, or the most modern, such as Budapest’s ghastly House of Terror, a secret police museum ringed by the word “Terror” in English rather than in Hungarian.

At the end, it was no doubt easier traversing the streets and boulevards of Western Europe without looking over my shoulder for cops or thugs. Officialdom was stringent in its own ways as I found with a Swedish official who stared at my well worn passport for a full five minutes before handing it back and recommending I get a new one – but I knew full well I wouldn’t have to worry about bribes, theft or worse. These countries, and their immigration patterns, were different but by casual observation nearly identical: instead of say, interracial couples strolling down the street or media personalities of colour gracing the screens of high end electronics stores, Africans and Asians were mostly tucked away into ethnic enclaves, managing corner stores and open air markets. Stockholm, Vienna, Rome and Paris seemed closer to California, and its Hispanic underclass, than Canada’s relatively freewheeling urban cosmopolitanism. Middling differences maybe, but with the City of Light still smoldering from recent riots, they were certainly telling ones: aside from a Polish waitress, virtually everyone at a Parisian bar I frequented were Arab males, chatting on cell phones and sipping on virgin cocktails. I’d be surprised if their alienation with contemporary European society didn’t boil over earlier in the fall; then again, history shows nothing’s more authentically Gallic than pitched street battles with the police.

Needless to say, I experienced reverse-culture shock in small, “funny that” sort of ways when I came back to Canada. I missed some of the finer aspects of the continent, particularly the food and drink, but it was good to be back home. With recent events now forcing Europe, old and new, to question its identity and its commitment to a multicultural future, there’s no place like it.

WORDS SAMEER SINGH

COMMENTS

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE

Newsletter Sign Up

Subscribe to our FREE newsletter for all of the latest news, articles, and videos delivered directly to your inbox each day!