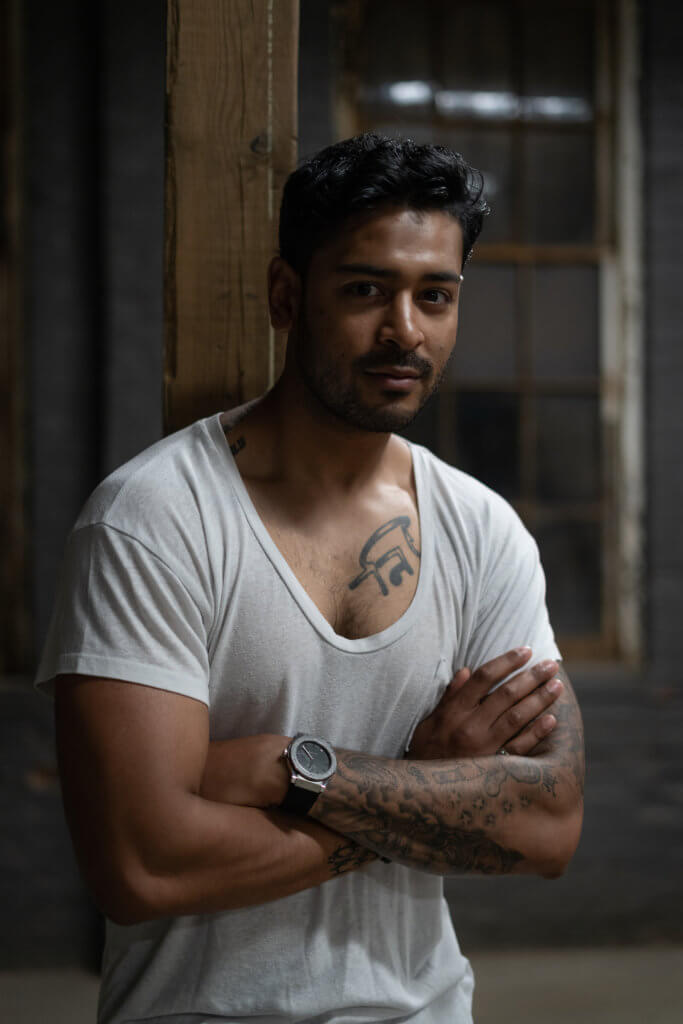

Actor, Producer, Writer Dana Abraham Shares Why He Couldn’t Pass Up “Neon Lights”

Entertainment Aug 18, 2022

A multi-hyphenate in the creative world, actor, producer and writer Dana Abraham — instead of waiting for a seat — decided to build his own table. Co-founding the Toronto-based production company Red Hill Entertainment, the 31-year-old Hamilton, Ontario native is telling stories on his own terms. Here, Abraham tells Anokhi Life about his latest: Neon Lights, a mind-bending thriller whose twists and turns mask a deeply personal exploration of mental health and childhood trauma.

In the entertainment business more than most, you have to create your own opportunities. Success if often more perspiration than inspiration, to steal a phrase from Thomas Edison. In the case of Dana Abraham and his new thriller Neon Lights, no one can say the sweat equity isn’t there. The Bangladesh-born, Hamilton-raised actor co-wrote the film, plays the lead and scrounged up the money to make it at the height of the pandemic — via a production company he himself co-founded. He even managed to lure a pretty big star to share the screen with him in this little independent picture: Sons of Anarchy’s Kim Coates.

Now available to rent on VOD services like Apple TV+ and Prime Video, Neon Lights finds Abraham playing Clay Amani, a tech CEO on the verge of losing his company — and possibly his mind. He decides that a trip to the country to reconnect with family is what’s necessary to get life back on track, but alas, not long after Clay and his guests have arrived at their remote mansion, the bonds of reality begin to fray, and people start to disappear.

Recently, writer-producer-star Abraham spoke with us about using a thriller to explore mental health issues, his mission to make more than just a “popcorn film” and how his own path as an artist is rooted in childhood trauma.

Matthew Currie: Take us inside the process of getting this film off the ground. You are wearing a lot of hats on this production.

Dana Abraham: I had written the original Neon Lights back in 2018. Fast-forward to the pandemic, Rouzbeh [Heydari, the film’s director] and I met, and we really wanted to work together. But with the restrictions of the pandemic, the original screenplay was never going to work; it was larger in scope, a multitude of locations, many cast and extras, etc. So we basically distilled it down to what we were really trying to talk about, which was mental health and childhood trauma, and how we could deal with that through the twists and turns of a psychological thriller.

We went to camera late-October, early-November, which was essentially the height of the second wave. Every single day was so challenging, because we didn’t know if we were going to get shut down.

The film is a labour of love for a lot of us and it was condensed with so many restrictions, but in the end, I think this is just a remarkable film. What we’re finding is that people either really hate it, because they’re not really understanding it, or that people really love it, because of, what one individual wrote, “the mental gymnastics” that it causes you to have.

Matthew: It’s interesting that we’ve become so obsessed with this idea of consensus, with the Rotten Tomatoes score. But you could argue that interesting art should be divisive.

Dana: The most important thing is: you don’t want anybody to sit in the middle. At the end of the day, if you’re going to create a body of work, you want people to either love it or hate it. The middle is lukewarm, and you don’t want that. For us, we’re super-excited, because we’re finding that the people who are excited by the challenging factors of this film and stuck all the way through it, are really enjoying it and they’re watching it a second time. When Rouzbeh and I were writing this film, we knew when we read the second or third draft of this script and we sent it over to Kim Coates and his team, we knew it was a challenging film — it challenges you to think, it challenges you to pay attention to every detail, and by the end of the film . . . if you can spend enough time all the way down to the very end and watch it, it ties everything back in. And then the final seconds, it’s really up to the audience’s perception what they think is real and what isn’t real, and what happens next from there.

Matthew: What is the larger thematic significance of those titular lights, all the different colours that bathe the screen in different rooms?

Dana: Originally, when I had written [the first draft], I was travelling through [a town] in New York, and this township was tiny — maybe 300-400 people. We went to this carnival, and in the carnival were all these neon lights. Then Rouzbeh and I, when we started to develop the screenplay that you’ve seen turned into a film, he’s so highly intelligent that he mentioned, “Let’s figure out a way to inspire these lightings to match the personality traits of these characters. That way, it has more of a motive and purpose.” That’s when we really distilled down and focused in on the lighting matching the traits of these characters — green focusing in on prosperity and money, red focusing on anger and rage, and all of the different facets that are tied into the colour.

Matthew: How was it working with Kim Coates? He’s a pretty unique guy when you meet him in person.

Dana: [Laughs] He’s so interesting. I’ve loved Kim for a really long time. My friends and I, we grew up watching Sons of Anarchy. Then the second series he did where he’s the lead was called Bad Blood. I’m from a city called Hamilton, Ontario, where mob culture and biker culture are two of the most prominent cultures in the city; so we’re diehard Kim fans. When Neon Lights came to be and I wrote in [the character of] Denver, because of his characteristics, his demeanour and how quirky he is, [Coates] was the perfect Denver for Rouz and I. Right away we were like, “We’ve got to get him.”

Like you said, he’s super-interesting, he’s a great performer, he exudes confidence when he walks onto a set and commands a set. But having said that, he’s an even better kind of person than he is a performer. He used to give me a lot of confidence, he’s become a father figure to me. We speak quite often regardless of Neon Lights. He’s put me in touch with his management team in the U.S. That’s the type of person he is . . . just a good-hearted, kind soul.

Matthew: Is there an added resonance in releasing a film like this during the pandemic, when mental health has been such a struggle for so many people?

Dana: Absolutely. When March 2020 hit, it was a jarring moment for every single person. Not only did it affect us on a financial level, but it affected us on a mental health level, it impacted us on our romantic relationships, and every facet of our daily lives.

When creating Neon Lights, we could’ve taken two routes — we could’ve taken a route where it was a very limited, restricted psychological thriller, or we could’ve tried to send a message. And for us, it was about mental health. Rouz and I, when we were developing the story, we felt it would resonate more with the audience that cared enough to sit there and focus on the distilled story than something that was more of a popcorn flick — which I don’t think we need more of. If you go onto any streaming platform right now, you’re going to find enough popcorn flicks where you can just watch through it, go on your phone and don’t feel any sort of mental challenge. With Neon Lights, what we were hoping for was to create a body of work that did challenge you both mentally and emotionally, to look introvertedly to see what part of your life can you connect with when you watch Clay Amani unravelling, and what are the questions and answers you have for yourself? The world premiere was in my hometown in Hamilton, with over 625 guests, and that was exactly what were receiving in the feedback.

Matthew: Do you feel like your own tumultuous childhood pushed you to become a storyteller?

Dana: Oh my gosh, absolutely. We grew up in poverty. My dad essentially abandoned us in Canada, took our passports, disappeared; he had a whole other family [back in Bangladesh] we didn’t know about. I haven’t seen my dad since I was seven; my little sister’s never seen him. I grew up in a neighbourhood called Oriole Crescent, which is a lot better now, but it used to be an epicentre of drugs, prostitution and gang violence. I grew up as rough as you could imagine. All the childhood trauma, it really started permeating into negative outbursts of behaviour around my early 20s, where I was behaving out of context of who I was as a person — somebody who was raised well by my mom, somebody who really had strong foundations of compassion and kindness. Any time I’d have a drink, it would result in something negative — an outburst, a fight, whatever.

And as I started to become more aware of who I am and started to lean towards art . . . that is the only way I can kind of express my childhood and who I am as a person. Neon Lights is a direct reflection of all the different mental battles with depression and how I’ve navigated that terrain over the years.

Main Image Photo Credit: Red Hill Entertainment

Matthew Currie

Author

A long-standing entertainment journalist, Currie is a graduate of the Professional Writing program at Toronto’s York University. He has spent the past number of years working as a freelancer for ANOKHI and for diverse publications such as Sharp, TV Week, CAA’s Westworld and BC Business. Currie ...