“What If A Mother Divorced Her Dead Husband?” – ‘The Roof Is Leaking’ Play Explores Why

Community Spotlight Apr 21, 2025

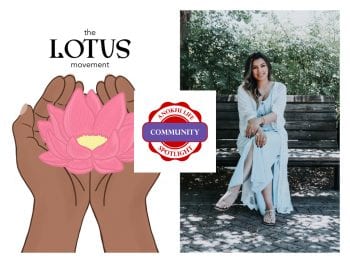

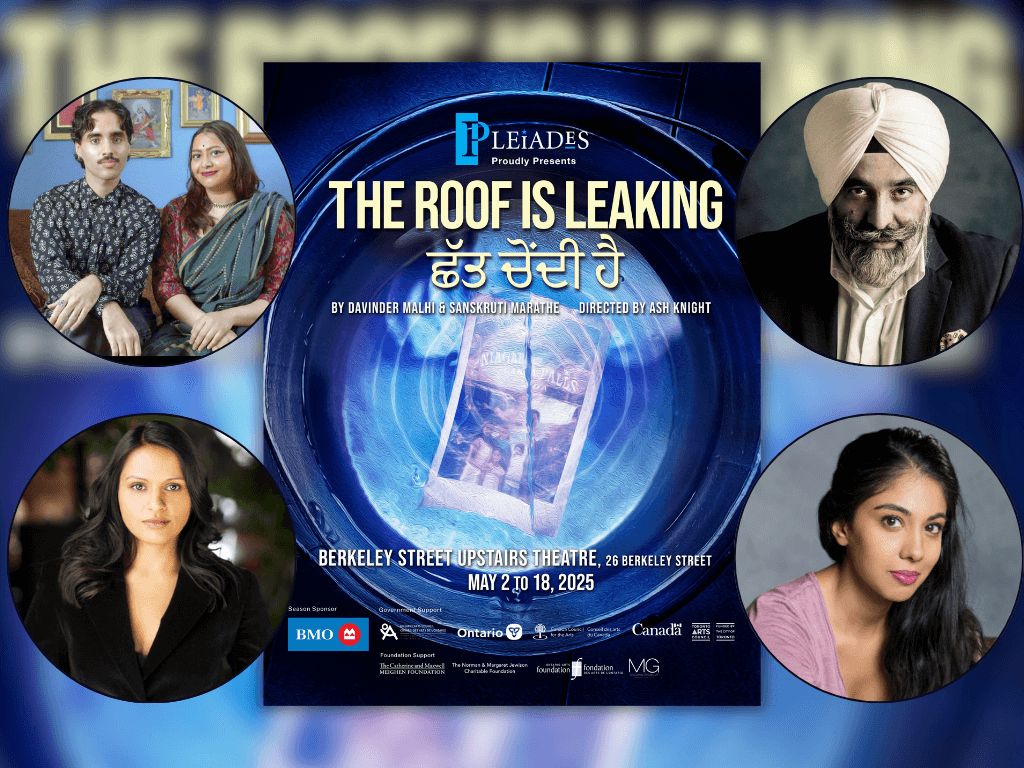

This spring, a powerful new South Asian story is taking center stage in Toronto. The Roof is Leaking (ਛੱਤ ਚੋਂਦੀ ਹੈ), co-written by Sanskruti Marathe and Davinder Malhi and presented by Pleiades Theatre, premieres May 2–18, 2025, at the Berkeley Street Theatre Upstairs.

Tickets are PWYC from $10. For more information, visit PleiadesTheatre.org or CanadianStage.com.

Set in Brampton, a city rich in Punjabi-Canadian life and culture, this deeply personal and darkly funny play explores themes of duty, intergenerational sacrifice, identity, and what it means to truly see the people closest to us.

At the heart of the story is a grieving, middle-class Punjabi family. When the patriarch dies, their world unravels, and the matriarch makes an unexpected and emotionally loaded decision: to divorce her dead husband. In doing so, she attempts to reclaim the freedom she lost in a life defined by sacrifice.

The play is, as the creators say, “a love letter to South Asian mothers.” It delves into the invisible labor and unspoken strength of women who quietly hold families together while slowly losing parts of themselves. As each family member confronts loss, love, and tradition, the play raises bold and necessary questions:

How much can we truly ask of our mothers?

What do South Asian families give up in order to uphold tradition?

What must we break to create freedom for ourselves—and for each other?

A Groundbreaking Moment for Representation

Starring a dynamic ensemble – Harry Gill, Tia Sandhu, Sarabjeet Arora, Kiran Kaur, Sarena Parmar, Harpreet Sehmbi, Harit Sohal, and Dharini Woollcombe – The Roof is Leaking is an important moment for South Asian representation on Canadian stages.

For many audience members, it will be the first time they see their family dynamics, cultural tensions, and emotional truths explored with nuance and depth in a theatre setting. And for the creators, it’s a chance to invite local communities to reflect on the lives and sacrifices of the women who raised them.

The production is part of Pleiades Theatre’s 2024/25 season titled Fragmentation: Part 2, and promises to balance both comedy and deeply stirring moments. With general seating available at Pay-What-You-Can rates (minimum $10), the show is accessible, intentional, and built for the community it represents.

Tickets:

Location: Berkeley Street Theatre Upstairs, 26 Berkeley St, Toronto

Dates: May 2–18, 2025

️ Tickets: Available here (PWYC with $10 minimum)

More Info: PleiadesTheatre.org

Behind the Scenes with The Playwrights

We caught up with co-writers Sanskruti Marathe and Davinder Malhi to unpack the inspiration, heart, and humour behind The Roof is Leaking:

ANOKHI: What inspired you to write this story – you describe this play as a “love letter to South Asian mothers.”, what parts of your own experience shaped that?

Sanskruti Marathe & Davinder Malhi: This project was profoundly shaped by our own mothers and our relationships to them. It stemmed from a deep desire to celebrate them and acknowledge all they’ve given us. Their strength, resilience, and even their moments of frustration—and perhaps most movingly, the ways we as their children have sometimes overlooked their complexities—served as a powerful foundation for the work. Punjabi mothers, in particular, are figures whose stories are rarely spotlighted on stage, and we felt it was important to give them the space and voice they so deeply deserve. We were drawn to this story during a difficult period in our own families. The Roof is Leaking became a vessel for processing our personal grief and the struggles our mothers have endured. At the same time, it evolved into a beacon of hope—a way to reimagine how we see and connect with our families.

ANOKHI: Did you write with the Brampton setting in mind from the start, and what does that location add to the story?

Sanskruti & Davinder: Throughout the many iterations of this play during its development, one constant has remained: the setting—Brampton. Brampton itself is a powerful symbol of South Asian Canadian life and culture. It’s also home to Sanskruti, who has always felt a deep connection to the community and the warmth that exists there.

Because Brampton is so unapologetically South Asian, it creates a unique opportunity for storytelling. The characters in this play aren’t positioned in direct opposition to whiteness—their struggles don’t need to be explained or justified through that lens. This allows for a more immersive experience, one with less exposition. No one is trying to explain or defend their customs on stage.

Instead, the cultural context is simply lived. The strong South Asian presence in Brampton allows these characters to exist more comfortably in their own skin, to speak freely, and to fully take up space.

Our goal was to focus in, with care and precision, on the story of one South Asian household. Setting it in Brampton adds a layer of specificity and nuance that grounds the work in something deeply familiar and honest.

ANOKHI: How did you navigate balancing comedy with the heavier themes of grief, tradition, and personal freedom?

Sanskruti & Davinder: As we wrote, we discovered that comedy and humour are intrinsically woven into grief and tradition. There’s something deeply human—and often funny—about how we try to be seen in our pain, the rituals we follow without question, and the sometimes absurd ways we chase after freedom.

In the play, we meet this family in the wake of a very real loss: the death of their father. And yet, in the midst of mourning, Mummy declares she wants to divorce her husband—after his passing. It’s an action that might seem absurd to some, but it is deeply rooted in her emotional reality. The juxtaposition between a ritual we are familiar with and with one that we have no written script for creates a great tension. This tension between the serious and the “ridiculous” allowed us to move fluidly between humour and heavier themes. From a narrative standpoint, we believe that levity is essential when dealing with grief—they are, in many ways, two sides of the same coin.

ANOKHI: What do you think theatre offers to South Asian storytelling that film or TV might not?

Sanskruti & Davinder: Theatre offers something uniquely powerful to South Asian storytelling—an immediate, communal connection. There’s something deeply moving about sitting in a room with others and witnessing characters who could be your own family members live out their griefs, joys, and conflicts right in front of you. The intimacy is palpable—you’re not just watching, you’re feeling with them, fighting for them, rooting for them in real time.

Theatre is a ritual, and no two performances are ever the same. The magic lies in its liveness—the energy that flows between the performers and the audience, creating a shared emotional space. That transference is electric, and it makes the experience deeply personal.

And when a story is set in the very place you live, that connection becomes even more profound. There’s a particular kind of resonance in seeing your community, your language, your humour, and your complexities reflected on stage. It makes the experience not just meaningful, but unforgettable.

ANOKHI: What do you hope South Asian audiences take away from this story, and what do you hope non-South Asian audiences learn from it?

Sanskruti & Davinder: This is always a challenging question because it places us in the role of cultural educators—and that’s not what this play is about. The Roof is Leaking wasn’t written to explain or teach Punjabi culture. It’s a culturally specific story, yes, but it’s ultimately about the humanity of one family facing a moment of rupture.

While the play does engage with broader themes like patriarchy, generational trauma, and cultural expectation, these aren’t presented as issues to dissect—they’re personal, emotional landscapes we’ve lived and continue to navigate. This isn’t an “issues play”; it’s a story about people.

For South Asian audiences, we hope they feel seen—in the details, the tensions, the humour, and the contradictions. We hope it resonates in a way that feels familiar, maybe even healing. For non-South Asian audiences, we don’t ask for understanding—we invite curiosity. Curiosity about their own families, their own cultural legacies, and a recognition that deeply rooted stories can exist beyond the dominant narrative.

And at a time when South Asian communities are being scapegoated and misrepresented in Canadian media, we also see this work as a quiet act of resistance—a reminder that we are not outsiders. Our stories are part of the fabric of this country. We’re not going anywhere.

Above all, we hope everyone—regardless of background—leaves feeling like they saw a piece of their own home in this play.

Behind the Scenes With The Cast

We spoke to three of the show’s powerhouse performers about stepping into their characters – and the cultural conversations that followed:

ANOKHI: Who do you play in the show and what is their story?

Dharini Woollcombe: I play the Mother in the story. She is the driving force behind this family which is the story of a woman who struggles for her right to exist within the dysfunctional system of her family and culture. At the age of 50, after her husband suddenly dies, she begins to realize that she in fact does not know who she is beyond her role in catering to everyone around her. The question remains: what will it take for her to fight for her freedom when everything and everyone wants to keep her firmly in her place.

Sarabjeet Arora: I play Chacha Arjun, a man grappling with grief after losing his brother—his anchor, confidant, and moral compass. At 50, he’s adrift in a storm of love and resentment for his sister-in law (Bhabhi), haunted by the shadow of a sibling he idolized. What fascinates me is how his desperation to keep his brother’s legacy, turns and twists him into the story’s antagonist. It’s a tragic arc: a man who never intended to become the villain but is undone by loyalty turns toxic.

Sarena Parmar: I play Jaspinder. She is the eldest daughter of this middle-class Punjabi family in Brampton. She has always played referee in her parents’ marriage. But when her father dies, she must face her own life and make peace with her living mother.

ANOKHI: What drew you to this project and your character? Are there any moments in the script that personally resonated with you?

Dharini: What caught my attention in this script was that it is very much aligned with some of the questions we are currently asking of our society today. What is a woman’s place outside of the male oriented systems that are firmly rooted in our cultures?

What does a woman have to do to be seen as fully capable, whole, separate and still worthy? What is it that we as parents, and mothers are modelling for our children and daughters? Is there a way to fulfill the desire to care for others and yet maintain the right to also be our own person?

For myself, as an artist, a mother, a wife, I am discovering the delight and joy of sitting in my own power of being a woman. That is, to delight in expressing myself however way I want to, of showing all my colours in whatever way I please, and finally letting go of so many fears and sources of shame. I am learning that this freedom is what I have always been looking for and it is a right we can only find for ourselves. Finding in and for ourselves is where it starts. Which is what I feel this play captures with its unique blend of humour and complexity.

Sarabjeet: After three decades in community theatre, this role felt like jumping into the deep end of professional acting—and I just took that plunge. Chacha Arjun is unlike anyone I’ve played: a fractured soul in a dysfunctional family, worlds apart from my own life. The challenge? Finding humanity in his contradictions. There’s a scene where he lectures his nephew about “family duties” and that scene is raw, uncomfortable, yet relatable. We’ve all met people who weaponize love, and that complexity hooked me.

Sarena: I fell in love with these playwrights. This is their first play, it is so ambitious and moving. Seeing adult children navigating their relationships with their mother in a South Asian context is really exciting. It brings up so many questions specific to our community.

ANOKHI: How does it feel to portray South Asian experiences on a Canadian stage in such a layered, authentic way? Why is it important for more South Asian stories to be told in mainstream Canadian theatre?

Dharini: It is thrilling to be part of such an important and pertinent play. I am moved by the experience of working with so many South Asian and POC artists. Mainstream Canadian theatre is opening up, but it is still limited. Representing South Asian experiences on stage allows artists to actually reflect parts of themselves through an authentic lens instead of fitting into other peoples’ ideas of what it means to be part of the South Asian tapestry, it inspires a new generation of young South Asian artists to step up and know that there is a place for them in the creation Canadian culture and finally, it moves us closer to understanding that celebrating our diversity within our Canadian borders is what makes us strong and powerful. It is vital to continue to produce South Asian stories so that current and younger generations of artists and audiences can be reminded that each one of us is human first, and we all have similar struggles: to be seen, to be heard, to be understood, to want change, to want better, to need hope.

Sarabjeet: For years, South Asian narratives were relegated to the margins—stereotyped, tokenized, or ignored. But today? We’re not just “included”; we’re owning our space. Productions like Ek Qatra Khoon (a Dora-winning gem by Sally Jones from Rasik Arts in 2004) paved the way, proving our stories aren’t “niche”—they’re Canadian. When audiences see a Punjabi family’s struggle mirrored onstage, it bridges divides. It whispers: Your grief, your joy, your quirks matter here. They are all real, just like anyone else’s.

Sarena: It feels so grounding to rehearse with a group of South Asian artists. I think seeing these stories on mainstages remind us there is a place for South Asians in the arts as artists and as patrons. These buildings are for everyone and we should take our space in them accordingly.

ANOKHI: Have rehearsals sparked any personal reflections or conversations about your own family?

Dharini: As an adoptee from India, this rehearsal process was special. I was able to continue my journey of learning more about South Asian culture, and the Punjabi culture, in a organic and meaningful way. Connecting with first and second generation artists was moving and a unique experience for me.

Sarabjeet:

They say, “Art holds up a mirror”. While my own family isn’t this chaotic, rehearsals made me interrogate the silent fractures in immigrant households. There’s a scene where children are uncomfortable with Chacha Arjun’s “old-world” expectations about education and a job. To me that particular scene is not just drama—it’s the ache of cultural conflict. How do you ensure that your children do well without suffocating them with your ideas? I don’t have answers, but this play cracks the door open for that conversation.

ANOKHI: If your character could say one thing to the family that they never got to say in the play, what would it be?

Dharini: “Stop interrupting me!!!”

Sarabjeet: “Bhaaji, I built a shrine of your memory in my heart—but forgot to tell you I loved you while you breathed.” Chacha Arjun’s tragedy is that he worshipped his brother in death but failed to show his love and gratitude for his brother in life.

Sarena: “I love you. I’m proud of you.”

ANOKHI: What’s one thing you hope audiences discuss on their way home from the show?

Dharini: I hope audiences discuss the idea that many things can be true at once.

Sarabjeet: I want them to debate whether Arjun is a villain or a victim—and realize he’s both. But beyond the plot? I hope they leave buzzing: Why don’t we see more stories like this? Imagine a Canadian theatre scene where South Asian musicals pack houses, where our tales aren’t “exotic” but essential.

Sarena:

I hope audiences speak about the complexity of marriage and how our parents change as they grow older. I hope we can give our parents room to change.

The world premiere of The Roof is Leaking ਛੱਤ ਚੋਂਦੀ ਹੈ from Pleiades Theatre runs from May 2 to 18, 2025 in Berkeley Street Theatre Upstairs (26 Berkeley St). For more information, visit PleiadesTheatre.org or CanadianStage.com.

Play info and images provided by:

Katie Saunoris (she/her)

Publicist & Communications Strategist | KSPR