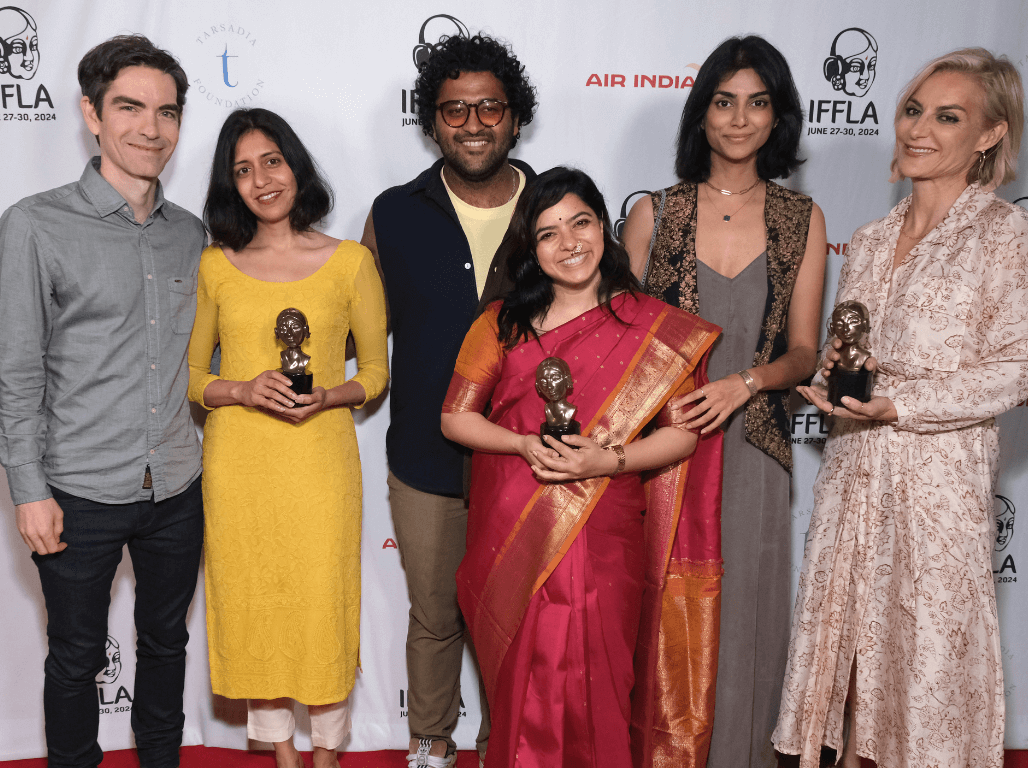

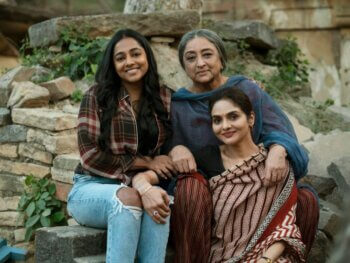

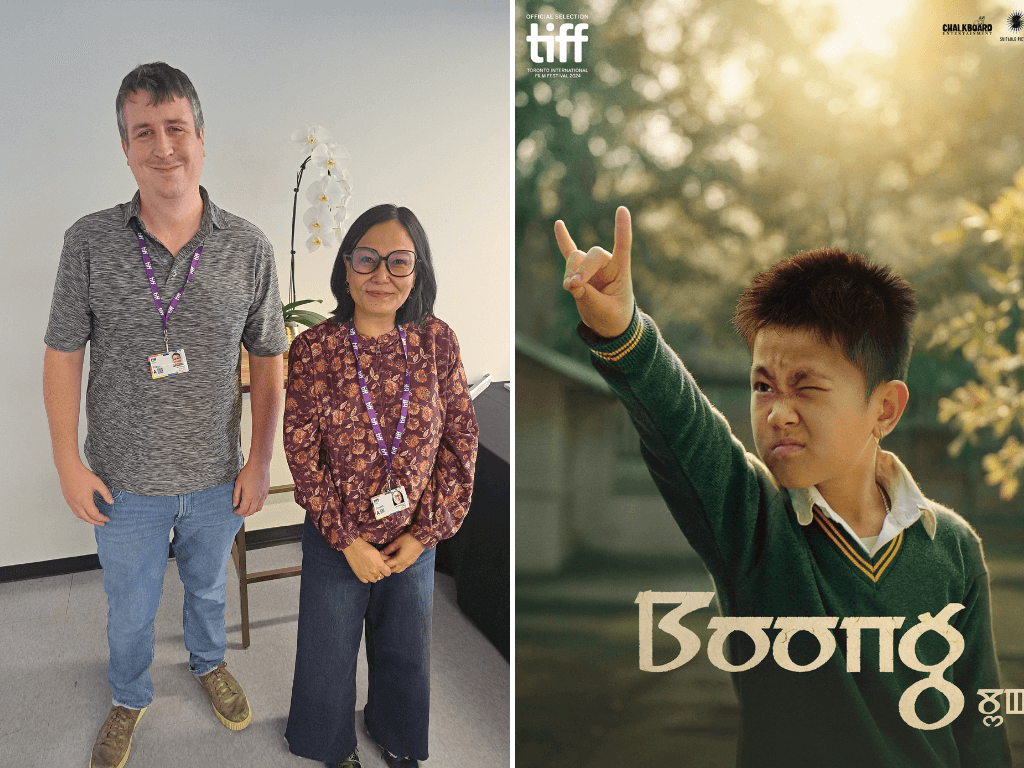

TIFF 2024: First-Time Filmmaker Lakshmipriya Devi Dishes On ‘Boong,’ Her Funny & Profound Modern-Day Folk Tale Told From A Child’s Point Of View

Entertainment Sep 13, 2024

Boong director tells ANOKHI LIFE about tackling heavy issues with a light touch, and the cinematic power of a child’s point-of-view

In a paradoxical sort of way, the more specific a movie is to a place, culture or way of life, the more universally relatable it becomes. Perhaps it’s the differences that highlight the fundamental human truths at the heart of any story.

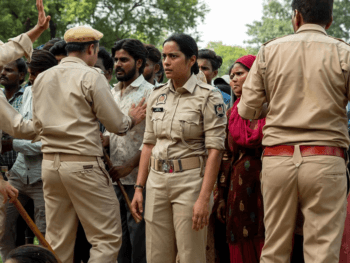

Such is certainly the case for Boong — the tender, funny, timely debut feature from writer-director Lakshmipriya Devi, which premiered at the 2024 Toronto International Film Fest. The film centres on rebellious, Madonna-loving schoolboy Boong (Gugun Kipgen), who is growing up in Manipur — a state plagued by simmering ethnic tensions on the verge of boiling over. Yet Boong is far too young to process such geopolitical conundrums. He’s more concerned with piecing his divided family back together; living with his selfless, savvy mom (Bala Hijam), the boy is obsessed by the very idea of his absentee father, who left Manipur years ago to launch a business on the Myanmar border and provide for the family. Every year, Boong expects his old man to return for the Holi festival, and every year he’s disappointed.

When tragedy strikes, Boong and his best pal Raju (Angom Sangamatum) embark on a bittersweet road trip to find dad and bring him home.

During this year’s festival, ANOKHI LIFE got the chance to speak with director Devi about the process of crafting a poignant coming-of-age tale inspired by her hometown of Manipur — specifically, the folk tales that echoed through her family kitchen growing up.

Matthew Currie: How was it, finally watching the film with an audience here at TIFF?

Lakshmipriya Devi: It was overwhelming. More than I expected. Watching it with people who don’t know anything about where I come from, I was expecting that it would be very alien for them, but I guess because the story’s universal, they got it.

I spoke to a lot of people [in the audience]. There were very few Indians; there were these teenagers, college students from here. They asked me very interesting questions about the character of the mother. They also asked me if they could do something to donate for Manipur. I was happy that, beyond the film, they had an awareness for a place that is so far away from them, nobody has heard of, but they wanted to do something. It really touched me.

This guy from the U.K. told me it was very personal for him because his father abandoned him. He said, “I could identify with everything.”

MC: The movie is described in the marketing materials as a “modern folk tale.” Is that the place you were operating from creatively?

LD: Yes. When I was small, my grandmother would tell me all these folk tales. It’s very common in Manipur. We have a fireside, which is in the kitchen, and the grandmothers are making vegetables and they always tell you folk tales. We never used to have comic books so much; it was all storytelling. It stays in your mind more, because you are remembering the person’s voice narrating, and it evokes a lot of memories. The story also came from an absentee great-grandfather; his story itself was like folklore in our family.

MC: Given the plot’s roots in folklore and myth, you could very well have gone in more of a fantastical direction with how you shot the film, but it’s all very grounded. The wonder of it really comes from the innocent perspectives of the two children. . . .

LD: The way I wanted to depict it visually, there were two options — I needed to go real or we also have these styles of art and dance and drama that are kind of magical realist. But the story is so real, if the treatment was more fantasy it might take away from the story.

I don’t need to add any visual treatment to it. I was not making, like, a James Bond film. I just wanted to keep it really simple. With my collaborators — whether it was the director of photography or production designer or costume — I said, “We just have to keep it real, and very simple.” And the reference is Manipur. I don’t want to be showing visual references of some other film somebody has made. The place, the people, the colours, the skies — those are the references, and I wanted to be as true to it as possible.

Having said that, I really wanted to evoke memories of my childhood — of Manipur. It’s quite urban now, you don’t see many of those bamboo trees. I really wanted it to feel like my folk tale version of Manipur I had heard from my grandmother. In the village and certain festivals, I tried to keep it bare minimum, like what it was years before.

MC: How did you approach working with a child actor like Gugun, who is so young and inexperienced — yet he also needs to anchor your film?

LD: Firstly, when I was casting, it was very important for me that I could have a conversation with the kid, and not like he’s a kid — like a friend. Somebody you can chat with and say, “This happened, how would you react to that?” You don’t have to mollycoddle him. When we cast Gugun, he was spontaneous, he was smart, he was fearless, he asked me questions.

MC: This is your first film as a director, but you’ve worked extensively as a first assistant director. How was the transition?

LD: I was less stressed as a director. Because as a first AD, you have to be with a stick in your hand and taking care of the schedule, making sure you finish the shot. You have no time to think. As a director, I only had to think about the script. I didn’t have to worry about whether food was going to come for the crew!

MC: The film also spotlights the ethnic and racial tensions in which Manipur and surrounding areas are currently immersed. Does telling your story from a child’s perspective offer you a unique way of approaching that very dire reality?

LD: When I was studying mass communication, we used to deal a lot with AIDS. AIDS was very rampant at the time. One of my tools was puppetry. The teacher told us how, with heavy subjects, if you tell it with a lighter tool, it is easier to sink in — because people don’t like to be lectured. I think that stuck in my head.

When you come from a troubled place, people expect your stories to be really dark or sad, and I really didn’t want to do that, because not every story needs to be dark or sad — especially for people who are going through that. If I go through something which is traumatic, somehow I’ll find something to laugh about. It’s my way of dealing with it.

And I also like telling kid’s stories. I’ve always written kid’s stories, somehow, because I think my childhood was so important to me. That was the loveliest phase, as well as traumatic. But it was wonderful. I always write from the point of that time.

Matthew Currie

Author

A long-standing entertainment journalist, Currie is a graduate of the Professional Writing program at Toronto’s York University. He has spent the past number of years working as a freelancer for ANOKHI and for diverse publications such as Sharp, TV Week, CAA’s Westworld and BC Business. Currie ...