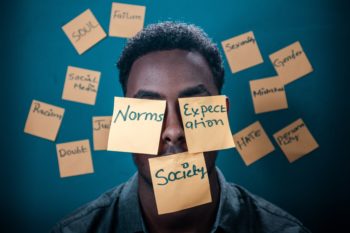

Your Schemas: Understanding Maps Of Information We Create Throughout Our Lives

Lifestyle Aug 18, 2021

We’ve all got them. We use them every day. We revise and make new ones all the time. Some of them help us, and some of them do more harm than good. Let’s explore schemas, how they work for us, how they sometimes get in the way, and what we can do to keep our schemas working for, rather than against us.

Dr. Monica Vermani is a Clinical Psychologist specializing in treating trauma, stress and mood & anxiety disorders, and the founder of Start Living Corporate Wellness. She is a well-known speaker and author on mental health and wellness. Her upcoming book, A Deeper Wellness, is scheduled for publication in 2021. Please visit: www.drmonicavermani.com.

Dr. Vermani has recently launched an exciting online self-help program, A Deeper Wellness, delivering powerful mental health guidance, life skills, and knowledge that employees can access anywhere, anytime at www.

From the day we come into the world, we are bombarded with sounds, sights, sensations, and experiences. When we are young, we begin to organize, categorize, and manage these overwhelming amounts of information. Very early on, something magical starts to happen. We begin to organize how people, things, places, and interactions between two people and among groups happen.

The pioneering Swiss child psychologist Jean Piaget introduced the term schema, to describe both the act of organization of large amounts of information and the resulting blueprint or maps that enable us to store, access, and make use of information. Young children, for example, easily learn how to ride a child’s tricycle once they have observed other children riding around and examined a tricycle for themselves. Increasingly, young children learn quickly how to manipulate electronic devices, by creating schemas through close observation of their parents and siblings who use their devices.

Schemas, Defined

Schemas are simply maps of information we — without even consciously doing so —organize, store and operate from in our minds. Each time we learn something new, or we’re exposed to a new environment, gadget, task, or interaction, from childhood onwards, we create a schema of it. These maps are extremely useful in helping us navigate the world and deal with the sorting of massive amounts of information.

The Upside Of Schemas

For example, Henry, at 25, in a single month, makes two major changes in his life. He moves away from his parent’s suburban home to the downtown area of a big city and starts a new job. He spends the first day in his new condo finding a place to purchase basic groceries, organizing his furniture and clothing, and figuring out how to get to his workplace on public transit. The first day commuting to his new job, he is hyper-aware of each subway stop, the stations, and street names, and the time it takes him to make his way to his office.

His first week on the job and in his new home has been stressful and challenging, but after a very short while, Henry is comfortable and confident. He knows what he is doing, who he is interacting with, and where he is going. He’s more relaxed and comfortable in his new world because he’s absorbed and expanded his maps of people, places, interactions, and even himself, therefore revising his existing schemas into more helpful, positive, and highly effective ones that make sense of his new world and how he operates and feels in it. Many of the tasks that Henry found stressful and challenging in the first few days in his completely new environment he can now perform without thinking about it, on automatic pilot.

And The Down

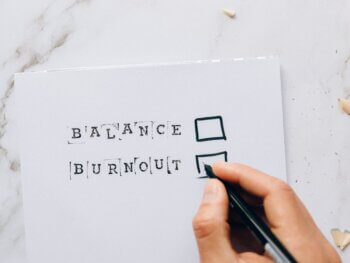

Just as schemas can help us make sense of the world, adapt to new environments and challenges in short order, and move through them with relative ease, they can also have a downside. When we experience, trauma, difficulties, or abuse, these negative experiences can overwrite our safe map of virtually any aspect of our life.

On the plus side, our parents are our first source of love and attachment, positive information about how relationships, conflict, communication, work. But on the downside, they can also be a source of early negative schemas about anger, assertiveness, prejudices, perfectionism, abuse, values about work, relationships, and love.

Emotional Debris

Through negative events, experiences or interactions, we can end up with emotional debris … negative maps about what relationships look like, what people’s intentions might be, how fairly or unfairly workplaces operate, how well or poorly men treat women, how trustworthy or untrustworthy friends might be, how welcoming or hostile people might be of people from unfamiliar backgrounds or cultures, how dangerous it is to drive, fly, walk around, talk to strangers, travel, take risks, try something new … the list goes on.

Emotional debris or emotional memory sometimes causes us to bring in safety behaviors … usually self-limiting fear-based actions designed to prevent feared situations or interactions from occurring again. For example, if Jane, who has taken many risks that have paid off as she moved from one job to another in her career as an executive recruitment officer, is left with emotional debris after a single negative job experience. Rather than move to another organization and find a better fit, as she had successfully done so many times, she chooses to step back from her successful career rather than risk repeating another setback.

Review And Rewrite

It’s important to examine our negative and self-limiting views about the way the world works, our fears, prospects, and possibilities. We need to reflect on the negative experiences in our life and whether these experiences have clouded our view and distorted our maps of the world.

We need clear, clean, and accurate maps of every areas of life. The good news is that we can revisit and review, retrace or revise maps that no longer serve us, and create positive schemas that help us make our way in the world.

Dr. Monica Vermani’s tips on revisiting the maps in our head

Be aware of emotional debris, unprocessed pain and trauma that negatively impacts the way you move around and interact with others in the world

Pay attention to any automatic negative thoughts or assumptions you have about the way the world works

Examine negative assumptions you may harbor about people, places, and possible outcomes

Challenge yourself to let go of safety behaviors

Consider the possibility that a negative situation is an isolated event rather than an established never ending pattern

Main Image Photo Credit: www.unsplash.com

Dr. Monica Vermani

Author

Dr. Monica Vermani is a Clinical Psychologist who specializes in treating trauma, stress, mood & anxiety disorders and is the founder of Start Living Corporate Wellness. Her book, A Deeper Wellness, is coming out in 2021. www.drmonicavermani.com