TIFF 2018: “The Man Who Feels No Pain” Director Vasan Bala And His Triumphant Return To Toronto

Entertainment Sep 21, 2018

A Bollywood kung-fu extravaganza took top prize in the Toronto International Film Festival‘s vaunted Midnight Madness lineup. We got to chat with the helmer of TIFF 2018 favourite The Man Who Feels No Pain just before this historic moment: Director Vasan Bala and his triumphant return to Toronto.

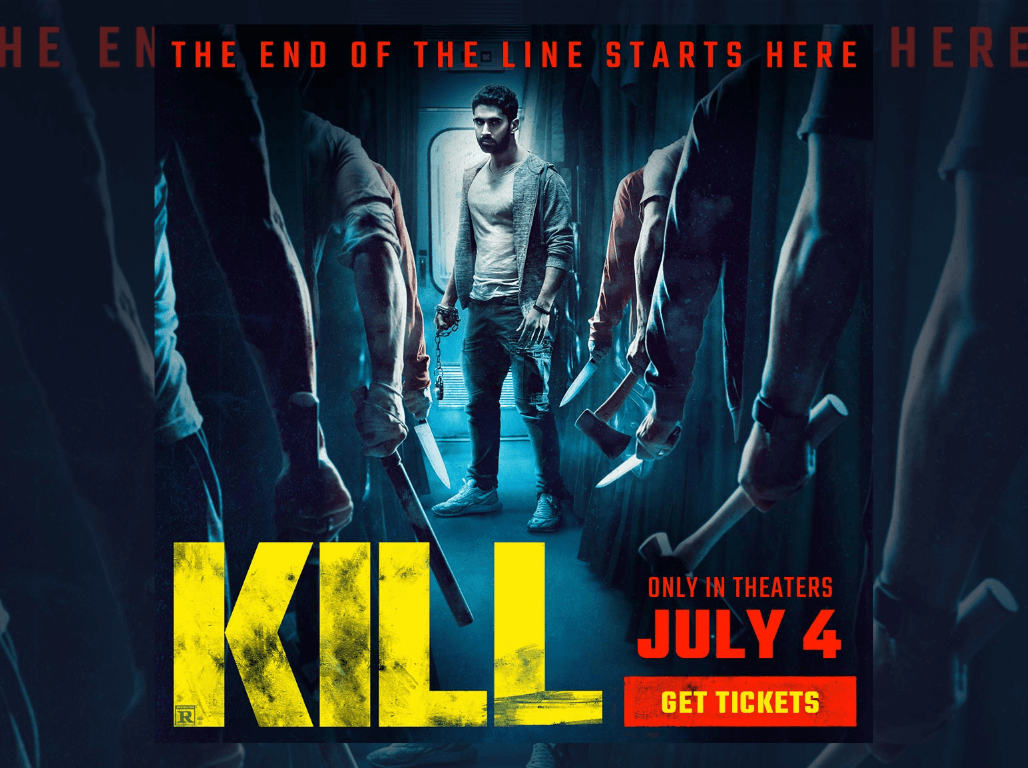

I first met Vasan Bala in 2012, when TIFF’s City to City spotlight turned its eye to Mumbai. He was in town promoting his debut feature, stark crime drama Peddlers. While that one flew under the radar, Bala’s sophomore effort, The Man Who Feels No Pain (Mard Ko Dard Nahi Hota) . . . well, it’s tough to be ignored when you’re both the first Indian film ever to screen as part of TIFF’s legendary Midnight Madness slate and the first Indian film to win Midnight Madness, with festival-goers recently voting the film to victory over competition like the Halloween remake and French provocateur Gaspar Noé’s much-buzzed Climax.

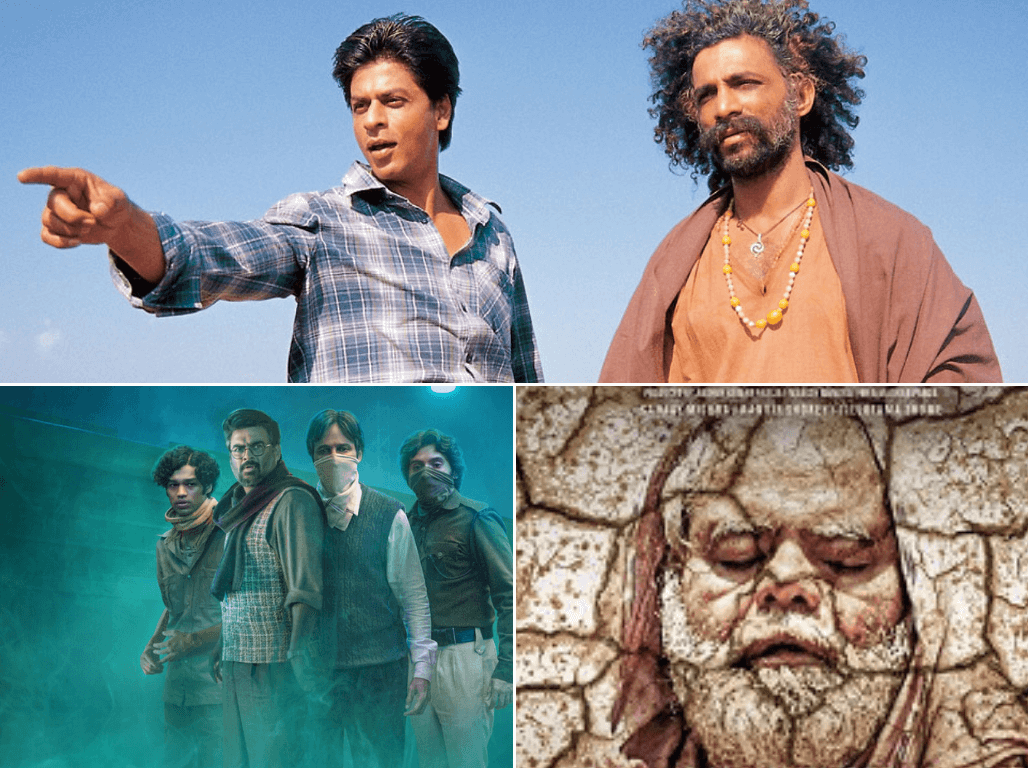

A kooky, kinetic, heartfelt love letter to the old action movies of Bollywood, Hollywood and Hong Kong, The Man Who Feels No Pain tells the tale of a boy born without pain receptors (played by newcomer Abhimanyu Dassani, son of Bhagyashree). It’s a rare, real-life condition and having it means that young Surya grows up alienated from his peers and eventually isolated from the outside world by his overprotective father. This leads the scrappy little upstart to an obsession with classic kung-fu pics, and over the years, he secretly uses his cache of grainy VHS tapes to turn himself into a martial artist/would-be crime fighter. Eventually teaming up with two fellow misfits — his childhood best friend Supri (Radhika Madan) and her washed-up, one-legged karate master Mani (Peddlers alum Gulshan Devaiah) — Surya becomes determined to compete in a 100-man kumite tournament. In the process, he and his new friends draw the ire of a vindictive crime boss — who happens to be Mani’s twin brother Jimmy (also played, with infectious gusto, by Devaiah).

In advance of the film’s Midnight Madness premiere on Friday, September 14, I sat down with the amiable, enthusiastic Bala at the TIFF Filmmakers’ Lounge to discuss what can only be described as a triumphant return to Toronto.

Matthew Currie: What does it mean to you to be the first Indian Midnight Madness film?

Vasan Bala: On one hand, it means a lot. And on another I am very surprised, because we are a country that makes a lot of Midnight Madness[-like] films, I believe. Intentionally or unintentionally. But it’s really cool. And also, that lineup! It has Shane Black [director of The Predator], Gaspar Noé, Halloween. It’s a little surreal.

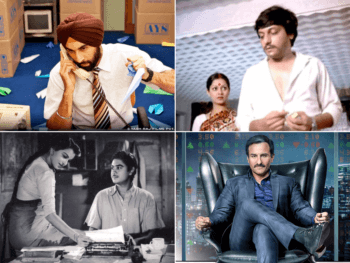

MC: This is clearly a film made by someone with oodles of affection for classic kung-fu and action movies. There’s a scene early on where your young protagonist is voraciously consuming VHS tapes. Were you channelling yourself at all?

VB: We were editing [that scene] and my mother walked in and said, “Oh, that’s you.” My wife [Prerna Saigal] is also the editor of the film, so my mother spilled all the beans to her. She said, “This is exactly what it used to be like back home.” It’s a privilege to make a film that is a conversation to your younger self. I hope I have the opportunity and the drive to keep doing that. I hope that’s what films mean to me, later on.

MC: And when you were writing the script, did you find yourself rewatching all those old favourites?

VB: Totally! What’s great is that when you’re not doing this academically, but more on an emotional level, all those films work. You don’t see it as 10-year-old me and a 40-year-old me. It’s the same. I enjoy watching Gymkata and Big Trouble in Little China as much as Enter the Dragon or Armour of God; no matter what the filmmaking was, the film speaks to you. The way we consumed movies back then, it was beyond all the technicalities. It was an emotional connection.

MC: As off-the-wall, funny and irreverent as the film is, there’s also this very poignant, emotional streak running through it, relating to empowerment and outcasts finding their place in the world together.

VB: That’s what I’ve been struggling with all my life. When you identify yourself with the fringe, you always have your back to the wall holding a drink, never at the centre, and that’s your perspective. I think so many filmmakers find their expression through that angle. And you want these people to be a part of the mainstream; and if not mainstream, then bring the party over to your corner.

That’s what the film is as well. You see the boy has a [medical] condition, there is an old man, there is a guy with only one leg, there is a woman who hasn’t found her place — all these people on the margin kind of standing up and having the cheap thrill . . . It might not be winning the gold medal for your country or doing anything great, but it’s finding their space.

It wasn’t about mad people in a mad world. You never set out to make a bizarre film, because that becomes too [contrived]. I always knew it was a drama; from Buster Keaton to Charlie Chaplin to Stephen Chow to Bruce Lee to Jackie Chan, there’s always drama, it’s always about the people — who happen to be martial artists, who happen to have brawls with each other.

MC: Let’s talk about casting. How did you settle on these three actors to play your heroes?

VB: Surya had to be a mix of not the typical Bollywood hero and yet in spirit be that. You know, we all are Sylvester Stallones somewhere inside, but we might not look it. Abhimanyu was found after a lot of time.

Also, in India, we don’t have a tradition of women doing these kind of martial arts. When I found Radhika, she had no interest in martial arts; she wanted to do hardcore Bollywood romantic films. But there was something in her gait, her walk, her personality that I was so sure she had to be a part of this universe. She came in, trained specifically only for the film, and she was amazing!

And Gulshan, obviously I’ve known for awhile. He was there in Peddlers, so I went back to him. He’d busted his knees, and I said, “I have something you shouldn’t be doing because of your condition, but I don’t think anyone else can do it.” And he took it up; he trained specifically for the film with literally one leg.

MC: Gulshan is great as both characters, but his performance as Jimmy is really something else.

VB: Oh yeah, ’90s Nicolas Cage madness! I love putting him in these characters and letting him loose.

MC: These big, elaborate fight sequences must have been a new filmmaking challenge for you?

VB: What we wanted to do was get away from the current rut Bollywood is going through. There were these YouTube videos I had seen of Eric Jacobus. He’s a martial artist from L.A. and he used to post these short films; I was always really intrigued because he was going back to the ’80s, giving homages to Jackie Chan and also in a very, very authentic Hong Kong action style, not really a Hollywood action style. And I was really sure, when I make this, it’s not going to be a celebrity action [choreographer] coming in, it’s going to be someone like him — a film fanatic who believes in a certain form of martial arts and a certain form of exploring martial arts in cinema. And I’m really thankful that the times aligned and he [and fellow fight choreographer Dennis Ruel] could make it. It’s a collaboration I cherish.

MC: Given all these influences from action films across the globe, do you think your movie has more crossover potential than your typical Bollywood piece?

VB: I think it’s only after the film gets made and after it’s sold, then you get into these discussions. I don’t think I’d ever be in a position to predict this with any of the films I make. To get the film made, I can lie [laughs] — but after that, I’d never know.

MC: This is your first film since Peddlers. What’s the journey been like for you these last six years?

VB: Back home, when you [to TIFF], you’re suddenly a filmmaker that’s been to a prestigious festival, but [you also hear] “This is not the kind of film that we need in India.” So the voices were very conflicting. I never thought to go out and make a Bollywood film or a non-Bollywood film. I was just making my own film. I’m not making an existential film about the Indian middle class wondering about life and death, neither am I making an out-and-out Bollywood film, neither am I making an out-and-out Hollywood-structure film. So you’re really not fitting in a proper box . . . You need to go through that. So you say, “These are the decisions, this is what I like and I’ll go through the path and it’s going to be a zig-zag.” I’ve made peace with the zig-zagging of it.

Main Image Photo Credit: www.tiff.net

Matthew Currie

Author

A long-standing entertainment journalist, Currie is a graduate of the Professional Writing program at Toronto’s York University. He has spent the past number of years working as a freelancer for ANOKHI and for diverse publications such as Sharp, TV Week, CAA’s Westworld and BC Business. Currie ...