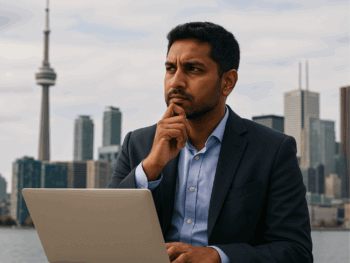

I went back to Uganda for the first time in January of this year, 35 years after my family and I were exiled in 1972 by then dictator Idi Amin. It has always been important to me to see why I am the person I am and if what happened in Uganda so many years ago is a reflection of that. As a filmmaker, I wanted to capture the search for my past, and so I left Canada on January 9, video camera in hand, to document my story.

Thirty five years ago, tens of thousands of Ugandan Asians – namely Indians – were frantically packing their bags to beat Idi Amin's deadline for them to leave the country. Accusing them of being "bloodsuckers", on August 26, 1972, the Ugandan military ruler told the country's approximately 80,000 Asians to leave and gave them until November 9 to do so. The vast majority did, leaving behind most of their wealth and possessions.

In Uganda, many Asians had become prosperous traders, businessmen and shopkeepers. Others were prominent in the medical profession or in education. But their success was not always to the liking of their Ugandan compatriots. Seeking scapegoats for economic problems and a quick way of seizing valuable assets, Idi Amin decided that they should be expelled.

Idi Amin offered several justifications for forcefully expelling the Asians. Regardless of their validity, it is indisputable that the exodus made Amin an instant hero in East Africa. Only later did the locals conclude it was misguided: first because of the disastrous impact on the economy, and second because the only ones to gain were Amin's soldiers.

Having been born in Britain, lived in Uganda to the age of three and then brought up as a Canadian, I feel drawn to Uganda like a lost child. I need to understand why this place, which I have never really known except through stories and old photographs, has such a hold on me.

All I know is, like so many other cultures that have been forced into exile and have settled in other countries, I had to go back – if only to give some closure to the experience.

While my parents do not ever wish to return to their homeland, I wanted to seek out the truth and experience of the events through the eyes of those who lived there, who had gone back or who had never left. This is not a history lesson but a story of heartache and loss. Like losing a soul mate, I know the only way I could be whole is to face the memories of my childhood.

Growing up, I heard stories about how beautiful Uganda was: how all the buildings were white, the water, clean and wherever you looked, everything was green. When my parents left in 1972, the population in the capital city of Kampala was 100,000. As I drive into the city, the first thing I notice is the condition of the roads. They are full of potholes and they are dirty. There are no distinct lane markers, streetlights, signs or even traffic lights. There is no order. People drive towards you, around you and they cut you off. And the buildings…yes the buildings are still there, but while the war ended 35 years earlier, they still resemble bombedout shelters.

The population is now 1.8 million in Kampala. People are everywhere. They are walking on the sides of the streets; hawking fruit that you can easily pick off the trees; hanging out in front of shops or begging on the side of the road.

Poverty is everywhere I look. Where has the beautiful city my parents told me about gone? Where are the brilliant white buildings, affluent markets and clean water? All I see is a city in disrepair, poverty-stricken and diseased. Small children, their mothers dead from AIDS, beg on the side of the street as I drive by. It’s a common sight for those who live there, but one that is difficult to accept coming from a country like Canada.

I thought that once I landed in Uganda, memories would come flooding back, but I realized that I didn’t and couldn’t remember anything because I was simply too young at the time. And what I thought I had remembered had just been conjured up from old photos and stories passed down through the generations of exiled Asians – my parents, uncles, aunts and grandparents.

I find the house in the district of Mango where my mother was born. It was still a pretty little house but the gardens, once so rich and fertile, are now dilapidated and poor.

I also find the house she grew up in and it is now converted into an office space. Ironically, a wealthy South Asian converted the house where my father was born into a parking lot just two years ago.

I also find the apartment building we were living in just before we left Uganda. It is a sad sight. Once a very beautiful building with paved roads, a garden and security gates, it now looks dirty and run-down, the gates filled with graffiti and the inhabitants looking equally sad. Outside the gates, the street is busy with boda-bodas (motorcycle taxis), street hawkers and people trying to avoid the numerous potholes.

Speaking to those who live in Kampala, I learn that most of them have become used to living in this condition and praise is high for the present government. They tell me when the Museveni government took power in 1982, there was no water, no power, no soap or sugar. Now, although power outages are still an issue, anything and everything is available in Uganda. Today in Kampala, the indigenous Africans and Asians alike run many of the shops.

But with every government, there are problems. African Ugandans openly complain about the corruption in the government and the lack of infrastructure. They say the investors’ money is not going where it is needed, such as fixing the potholes in the street. The poor road conditions are such a problem that in Uganda there is a running joke: a pothole requires five centimetres of tar to be fixed, but in Kampala, two centimetres goes into the pothole and three centimetres into Museveni’s pockets.

In Uganda, freedom of speech is still allowed, and while they complain about the potholes, they also complain about the lack of education for their children. At present, Uganda pays for primary schooling, but it still charges for secondary education.

With the national average standing at 7.8 children per family, it is difficult for a family to feed, clothe and educate the children. Plus, when a child gets sick with malaria, medication is not always available because it is either too expensive or if they live in a rural area, the people can’t afford to travel to see a doctor. Therefore, infant mortality is at an all-time high.

My cousin, who is the CEO of a major pharmaceutical company in Kampala, openly complains about the deal that the Museveni government made with the Bush government. Prior to 2005, there were signs all over the city teaching the locals to reduce family sizes or to use condoms or to even think about safe sex. In 2005, the Bush government asked the Museveni government to remove the signs with the support of the local churches and to use U.S. anti-malarial and AIDS drugs instead of locally made drugs. In turn, the Bush government would give financial aid to the country. The rates of AIDS-related deaths have once again increased and the infant mortality rates have also increased since most people cannot afford to buy the medication for their children. Worse, the money that is supposed to go to assisting the poor and the disenfranchised has only gone to support Museveni’s cause to buy more properties, including hotels and shopping malls.

The other problem affecting the country is the high rate of unemployment. Currently, there is 95 percent unemployment in Uganda. The government is not addressing this issue and the problem is steadily becoming worse. The people say when students graduate from Makerere University, they can’t find employment and end up working in the shops or on the side of the street selling fruit to people stuck in traffic. They can’t make enough money to support their families, let alone themselves.

“When this regime started into power in 1985, by 1990 things were okay. But when the government started restructuring ministries, they brought in these computers,” says Thomas Buregjeya.

Buregjeya is a local who works for an Asian businessman. He has watched the economy change over the years. He says that after the country brought in computers, the ministry started reducing manpower in all departments and began restructuring both the public and private sectors. Even those with doctorates are unable to find jobs.

“Formerly, after university, straight away – when the Asians were around – you could go straight away to the factory. We are not like Kenya. In Kenya, students finish university and they get jobs. Even if you are underpaid, you get something, but here you can’t,” says Buregjeya.

During my trip, I speak to Asians and Africans who remember the events of 1972. While I find a people who are oppressed and poor, I also find that they have a determined spirit beyond all of that. What strikes me is how friendly the Ugandan people are. I was expecting that after the oppression and tyranny they had faced over the years, they would be unwilling to trust and open up. Surprisingly, it is the exact opposite. When I tell people why I have come back and that it is my first trip, they thank me for coming and invite me to come back again. It was a nice feeling!

Walking in the Kampala marketplace, I notice the beauty around me. I see big mangoes (my favourite), guava, healthy vegetables, fish, meat, live chickens and goats – anything and everything. To my eyes, food is so cheap, but many Africans can’t afford to buy very much for themselves or their families. It puts things into perspective and makes me very ashamed and sad. I meet a local spice seller who invites me to visit his stall. He speaks about how hard it is to make money and live in Kampala. He lives in a small shack with his mother, his brothers, his sisters and his uncles. He says that ten people live in a small shack but life is good – they don’t have much but they have each other.

During my search for understanding, I am fortunate to have interviewed many Asians who never left Uganda; many who had left and came back to resettle in the 80s; and many Africans who, unlike the Asians, lost much more than properties and their homeland: they lost family members at the hands of Idi Amin. While 80,000 Asians were exiled, more than 400,000 Africans were murdered, simply because Idi Amin did not like or trust them. I am curious as to why some were willing to go back while others, like my parents, were not. Were they drawn to the country like I was? Or was there some other reason? What memories did they have that brought them back to this country?

I speak to three families that were influential prior to the exile: the Madhvani’s, the Hudda’s and the Metha’s. All of them had returned in the 1980s to rebuild and reclaim their properties. But their return was not an easy one.

Says Pratap Madhvani, “We came back in 1980 just to take a look. At that time, the government was in a bit of a mess. There was not much going on there. In 1982, I think there was an announcement from the government that the properties were going to be returned to the Asians…we thought, ‘let’s go and take a look here.’ We were not even allowed to look at our home the first time. They said, ‘you cannot go here.’ It was government property. Somehow we knew some people that were working here, and we came and looked and it was terrible.”

All three families speak to me about the state of their properties and the struggles they had to overcome to not only reclaim them, but also to rebuild their businesses and old lives. For them it is a struggle worth taking, but not everyone wants to return. While my parents are not as affluent as they were in Uganda, too much has changed in the homeland for them to go back.

Henry Kyemba, author of A State of Blood and Idi Amin’s health minister, remembers his own exile from Uganda in 1976: “I had considered going into exile many times, but going into exile is not the easiest decision you can make, even up to now. I feel Uganda is my home so it was not easy to make that decision. But then so many things were happening. I mean my mother was here, and she was old. I knew anything could happen to them if I left. But then when my mother said, ‘My son, I think you better go’, she knew it was a matter of time. I knew too much about what was going on, and she knew I would rather be in exile than to stay and see what happens.”

Going back to Uganda in search of my past included a quest to learn about my grandfather and the mark he left on Uganda. From what I know, he came to Uganda as a poor peasant from India, but then amassed a great reputation and wealth by bidding on government tenders in lumber. In 1968, my grandfather was recognized by the Pope for his lumber donation to the Rubaga Church and honoured with a plaque that was affixed to the church’s fountain.

I optimistically go in search of this fountain. I am ecstatic when I find the fountain still standing, but my happiness soon turns to sorrow when I discover that the plaque is missing and that the fountain is no longer operational. While the story still exists, the history has been removed, and next time I am in Uganda, I intend to find someone who can recount that time to me.

I’m not sure if I will ever be able to find an answer to why Uganda, a place I do not really know, feels like home to me. I do know, upon returning from my trip, that I miss it deeply. I miss the people; I miss the food; I miss the culture and most of all I miss the feeling that I belonged there – I was home.

When I first set out to make my documentary, it was about the exile in 1972 and the people that were affected by it. After visiting Uganda, I realize that it’s not the story of a country, but the souls of those that lived there. This documentary is about my personal journey to reclaim a past that was lost. Like many who have left their birthplaces due to war, politics, religion or any other reason, it’s the stories and images they create that preserve the country. And even though the country has gone on without them and the faded memory is all that remains, in the hearts of those who lived there, there is no place like home.

WORDS/PHOTOS AMINA MOHAMED

COMMENTS

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE

Newsletter Sign Up

Subscribe to our FREE newsletter for all of the latest news, articles, and videos delivered directly to your inbox each day!